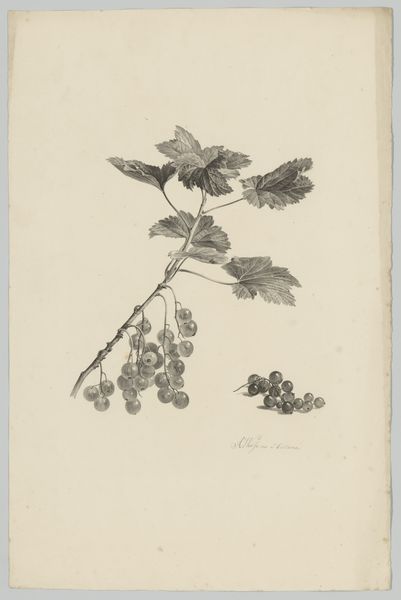

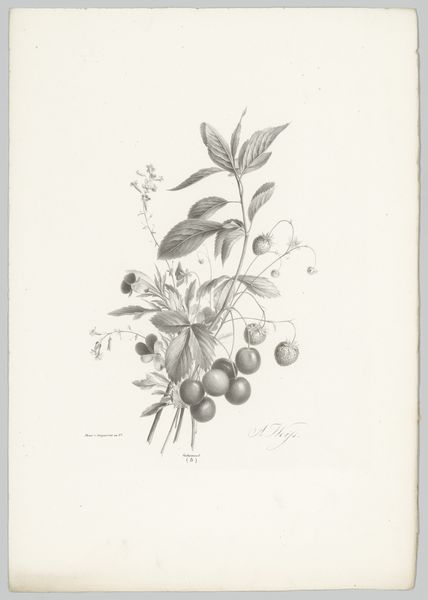

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

coloured pencil

#

pencil

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 214 mm, width 293 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

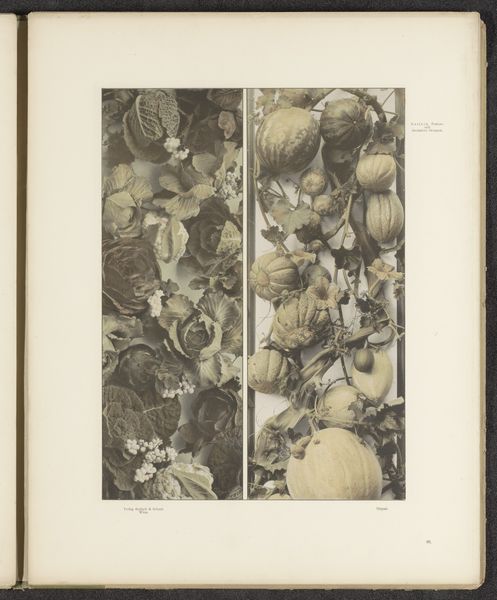

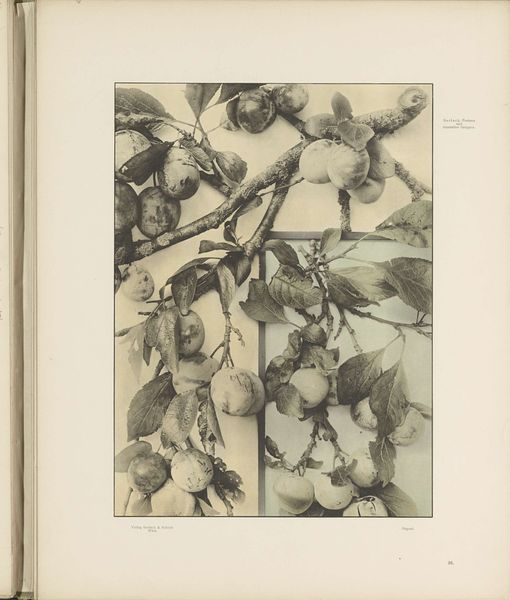

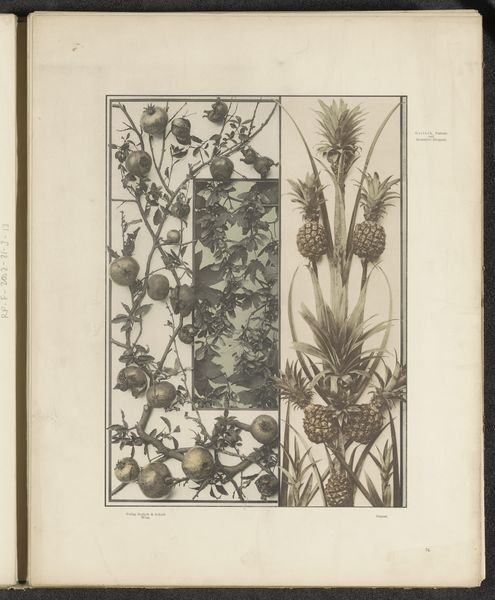

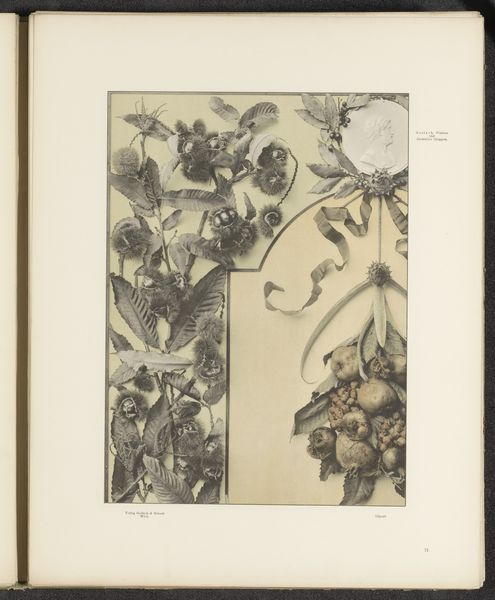

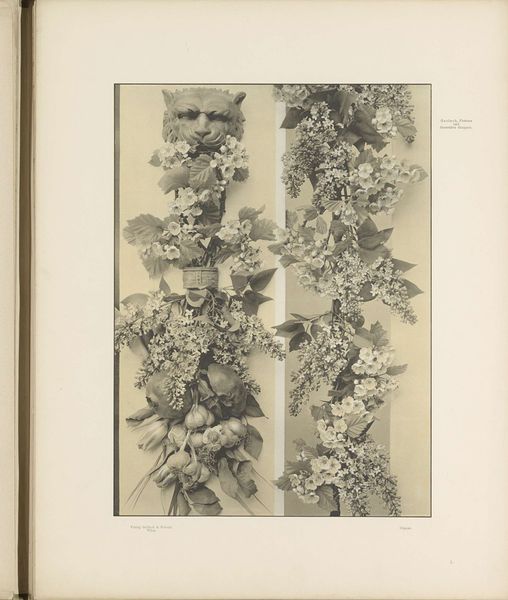

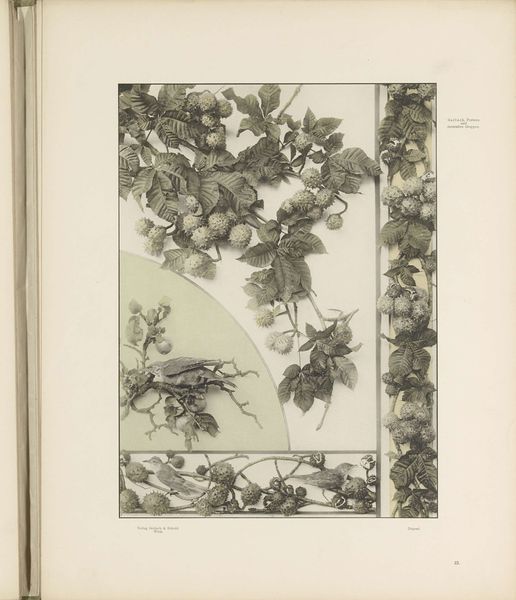

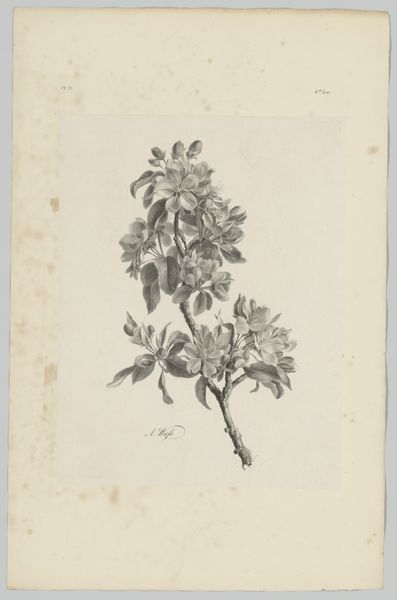

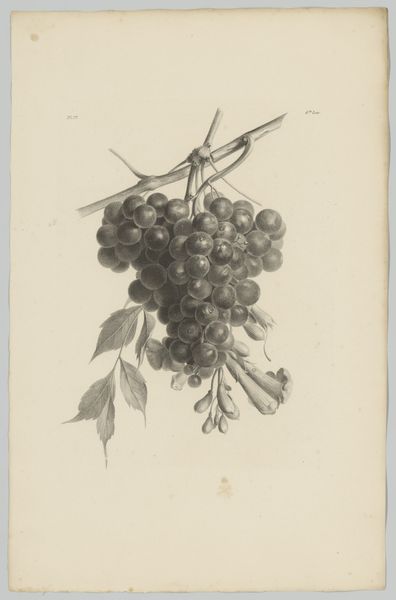

Editor: This is “Festoenen van kweepeer, tamme kastanje, citroen en meloen,” or "Garlands of Quince, Chestnut, Lemon and Melon," a drawing created before 1897 using pencil, colored pencil, and watercolor. There's a certain stillness to this composition of fruit; almost feels like a preserved moment. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Beyond its surface appeal as a botanical study, this drawing presents a compelling lens through which we can examine the relationship between nature, culture, and representation in the late 19th century. Consider the act of arranging these fruits—quince, chestnut, lemon, melon—into garlands. It’s not merely about depicting them accurately; it's about imposing an order, a human interpretation on the natural world. This impulse reflects broader power dynamics prevalent at the time. What might the selection and arrangement of these specific fruits tell us about the colonial context, trade routes, and class structures? Editor: That's a really interesting take, I was just seeing pretty fruit! Thinking about trade routes gives me a completely new perspective, especially because some of these fruits wouldn't naturally grow in the same region. Curator: Exactly. And consider the choice of rendering it in watercolor and pencil. This medium allows for detail and precision, aligning with scientific illustration. However, the artistic rendering elevates it beyond a mere document. What's striking is its potential to legitimize imperial power by categorizing the bounty of colonized lands, making them known, knowable, and ultimately, controllable? How might the seemingly benign botanical illustration serve as a tool of domination? Editor: Wow, I hadn't considered the way that cataloging could be a form of control. It’s like turning nature into a commodity, even through art. Curator: Precisely. By unpacking the historical and social narratives embedded within, we begin to understand that the botanical arts is rarely a neutral representation. Instead, they become rich sites of cultural exchange, power struggles, and ideological statements. Editor: This really encourages me to look beyond the surface of artwork to unpack their potential cultural implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.