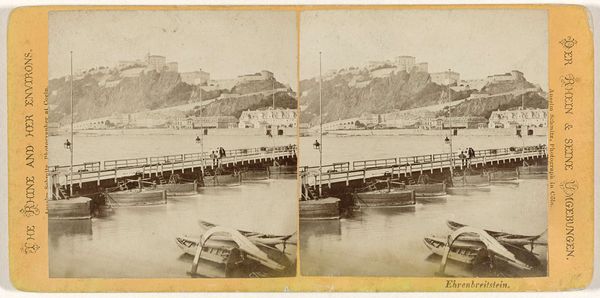

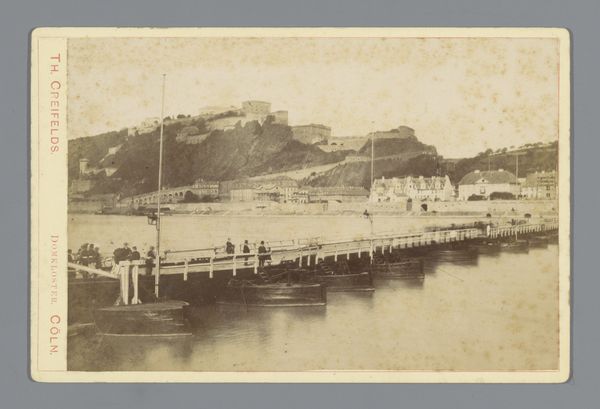

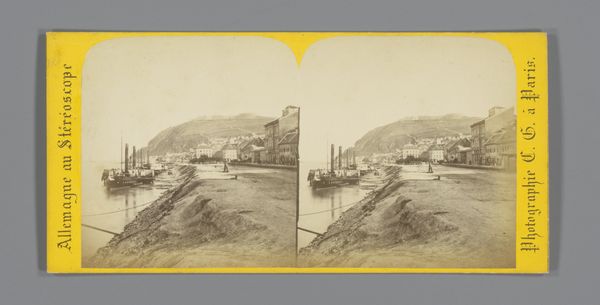

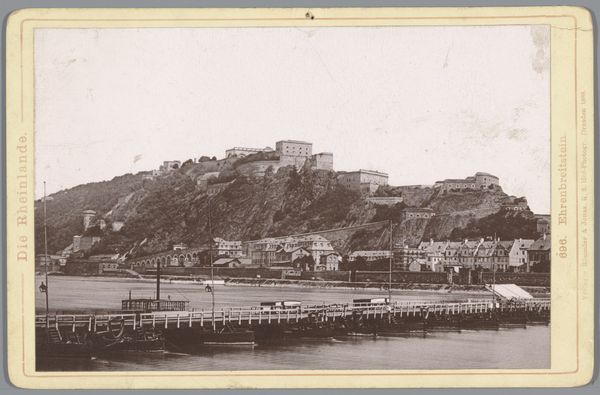

Scheepsbrug bij Koblenz, met Fort Ehrenbreitstein op de achtergrond 1869 - 1872

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 177 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this gelatin-silver print by Johann Friedrich Stiehm, dating from around 1869 to 1872, titled "Scheepsbrug bij Koblenz, met Fort Ehrenbreitstein op de achtergrond," my immediate sense is of a captured moment, a record, perhaps even a manufactured nostalgia. Editor: It certainly has that quiet, historical gaze. For me, the bridge itself dominates the image, a practical construction made of timber, designed for movement and commerce and connection. How did these structures impact daily life in Koblenz at this time? Were there social divisions reflected in who could use it? Curator: Absolutely. These early photographic processes democratized image-making in some ways, opening the door for wider representation. Note the process, though, a gelatin-silver print. Consider the chemistry, the industrial production of photographic materials, the labor involved in creating this single image and then the potential for mass reproduction. The materiality of it speaks volumes about its historical moment. Editor: That’s an important point. Beyond the labor, how do we view the figures on the bridge? Their inclusion gives scale but they're also anonymous. Who were these people crossing, and what stories do they bring, consciously or unconsciously shaping our own perceptions and the historical narrative this photograph conveys? Are they just props to showcase the landscape or do they suggest a new way of life afforded by the industrial revolution, connecting different demographics for exchange? Curator: They could well be indicators of change! Stiehm carefully frames this new reality—industrial advancements juxtaposed against an older structure. Consider that Fort Ehrenbreitstein on the hilltop; that building is not a neutral landmark. What kind of material and financial resources had to go into that fortification? Editor: True, its presence signifies power structures. The photograph doesn’t simply depict a location, it offers a particular framing of nationhood and military prowess, intentionally presented for the consumption of the burgeoning middle classes and foreign visitors eager to tour a country with an elevated historical significance. It makes you question what is promoted or censored at each stage. Curator: Exactly, it makes us reflect on how photography was employed not just as a tool for documentation, but also as a powerful force in constructing and disseminating a specific kind of German identity at this crucial historical period. Editor: So while this image might seem simply a snapshot of 19th century Koblenz, it unveils complex dialogues about production, power, identity and how each plays into the social tapestry of the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.