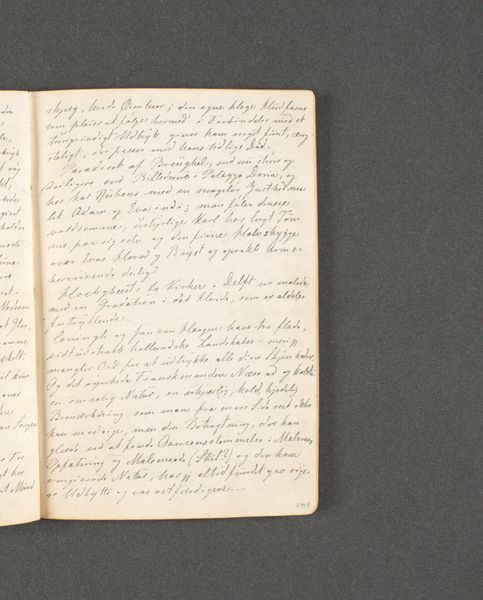

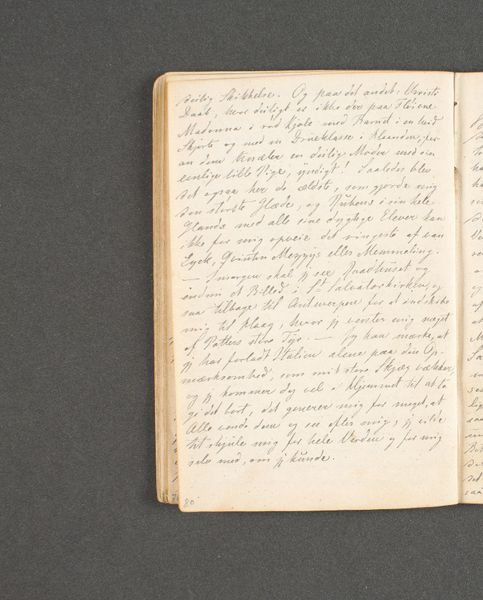

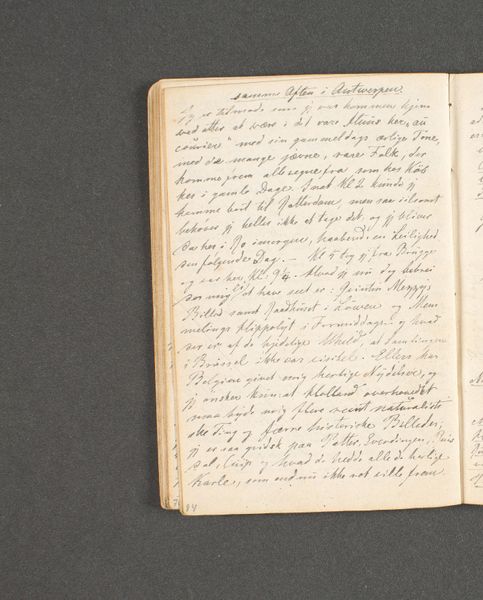

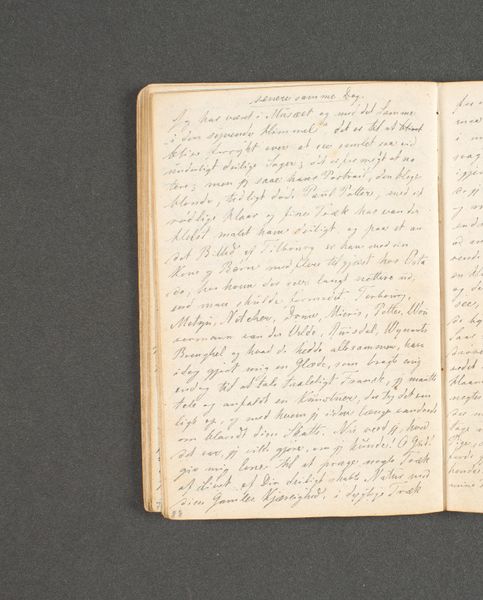

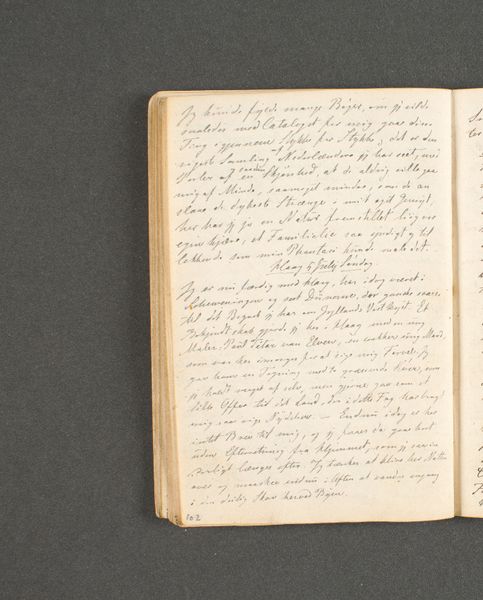

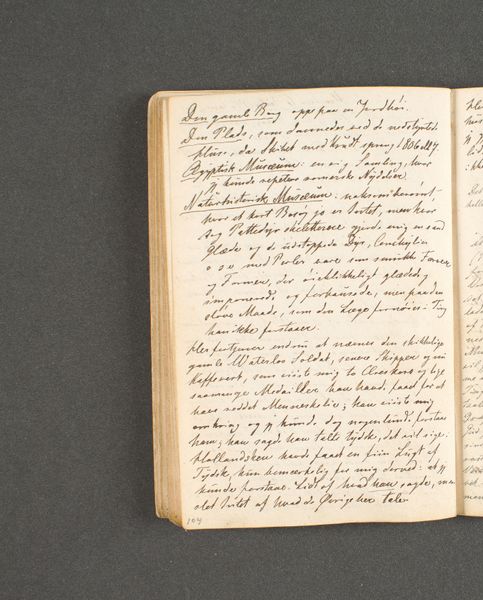

drawing, paper, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

sketch book

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

pen

#

miniature

Dimensions: 131 mm (height) x 89 mm (width) (bladmaal)

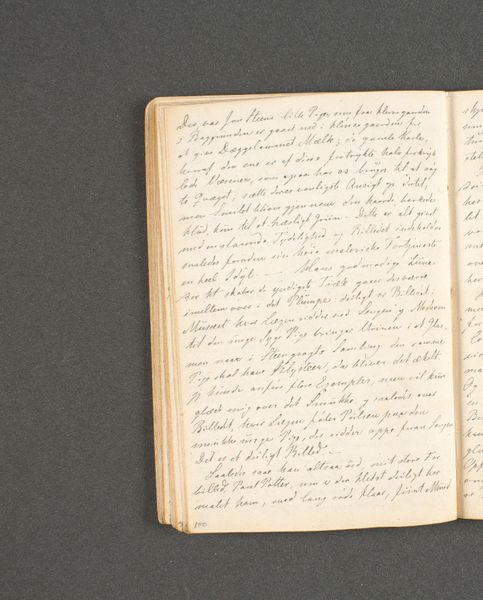

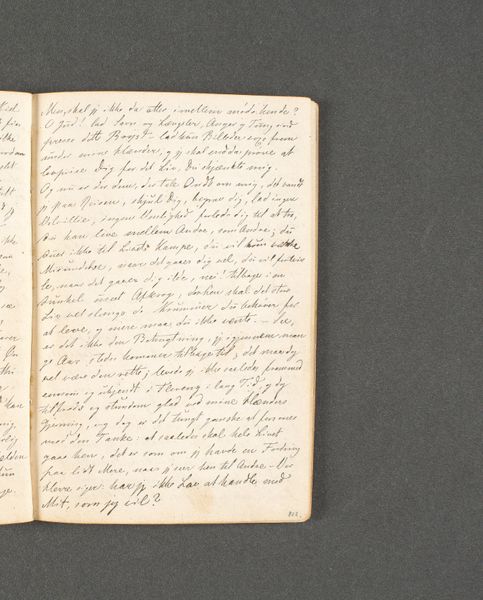

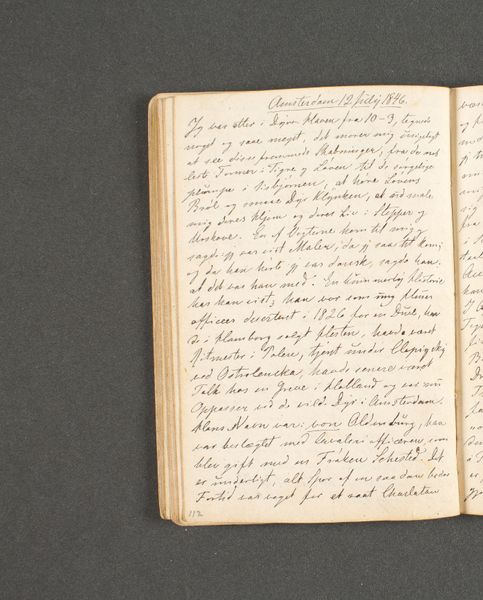

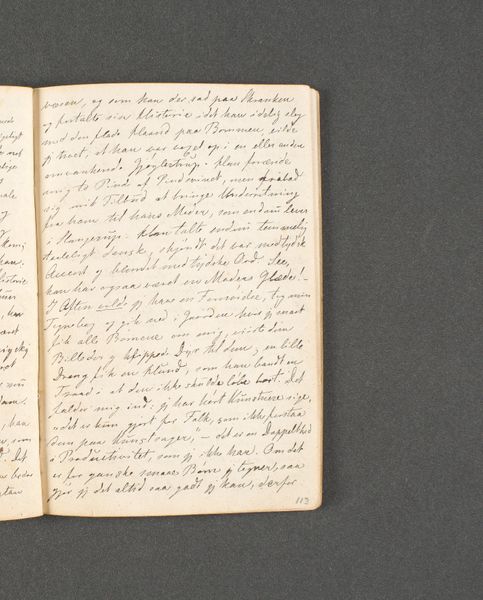

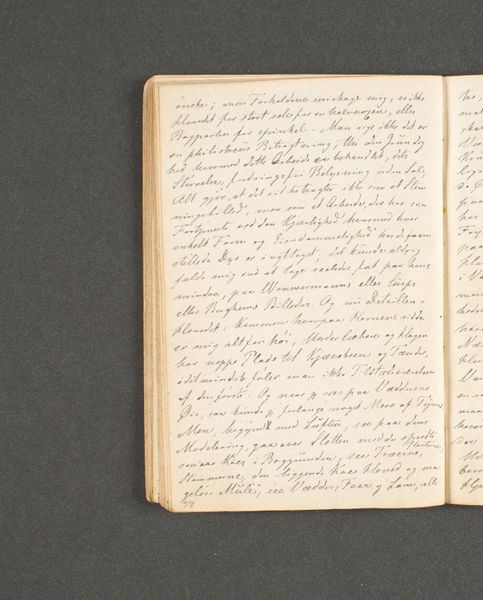

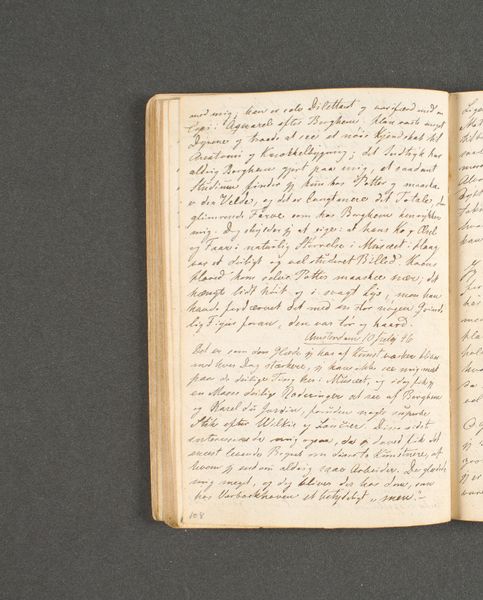

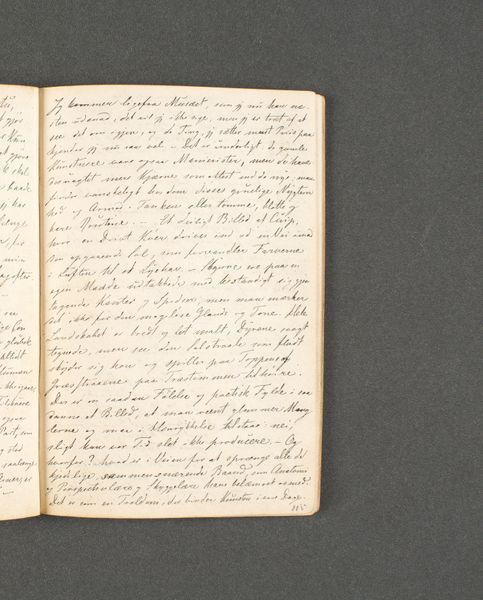

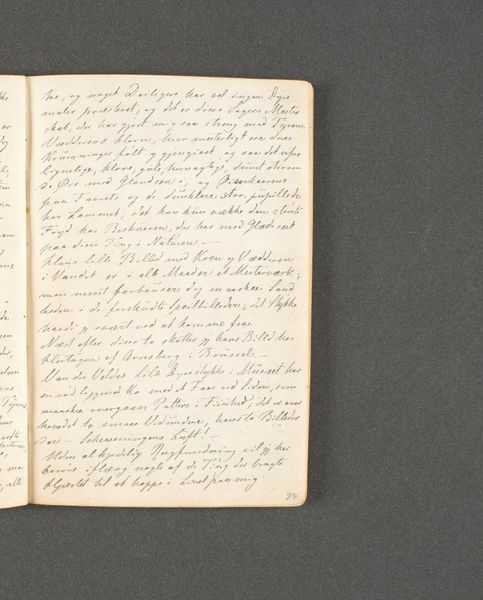

Curator: This pen drawing on paper is titled "Rejsedagbog. Amsterdam," which translates to "Travel Journal. Amsterdam." It was created by Johan Thomas Lundbye in 1846 and now resides in the Statens Museum for Kunst. Editor: It looks like an intimate glimpse into the artist's private thoughts, almost like peering over their shoulder as they jot down observations. There’s a certain quiet intensity to the scrawled script. Curator: Absolutely. As a travel journal, the miniature serves as a portable repository of experiences. In the Romantic era, the sketchbook evolved into more than just preliminary studies; it was seen as a space for capturing the immediate sensations of travel and reflection. The hurried writing conveys the sense of fleeting time. Editor: Do we know more about why Lundbye was in Amsterdam? How might understanding the journey contextualize the marks made here? Are there social and political undertones shaping what is included, what is omitted from this personal document? Curator: Sadly, the page exhibited from this sketch book is missing accompanying imagery, which makes finding answers challenging. However, Lundbye, a Romantic painter, frequently worked with themes of nature and the sublime, connecting to feelings, memory and the symbolism of personal experience. Text becomes as equally important as a picture in recording observations of travel. It suggests not just what he saw, but what moved him, what he sought to understand. The handwritten nature becomes like a code to break, it gives unique insight. Editor: That act of recording, the labor of writing, especially at that time, was often a highly gendered activity. Were journals primarily a space for white European male introspection? This glimpse into Lundbye's journal prompts so many other questions of access, and I wonder whose voices, literally or figuratively, are excluded from this “personal” historical record? How do broader structures shape intimate thoughts, the choice of detail, and the nature of looking? Curator: Those questions are vital. By the 19th century, written languages acted as visible forms and signs, embodying an almost divine nature, and this miniature page reveals what Roland Barthes defined as “the pleasure of the text.” Editor: Definitely. The scale invites us into that sense of personal pleasure. Looking closer, I am touched by the labor and dedication the writing conveys. I value the opportunity this provides, opening doors into a particular life, in a particular moment, with such distinct sensitivity. Curator: It is truly an honour to reflect together, adding new layers of appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.