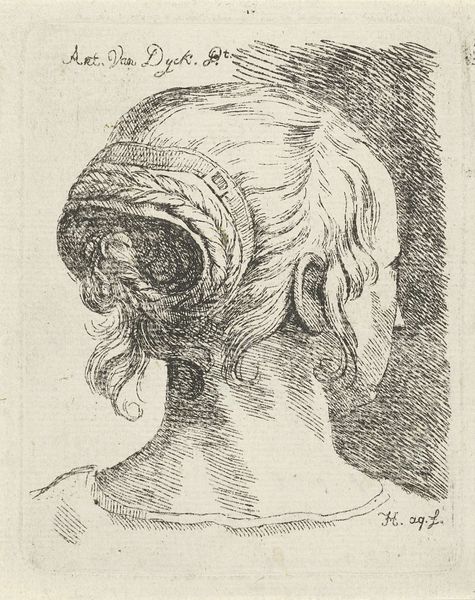

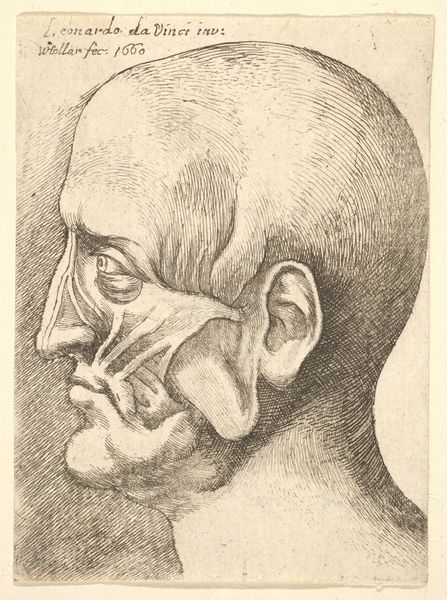

Anatomische studie van hoofd en schouders van een man, ontleed 1651

0:00

0:00

wenceslaushollar

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 125 mm, width 65 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us we have Wenceslaus Hollar’s “Anatomische studie van hoofd en schouders van een man, ontleed,” or “Anatomical study of the head and shoulders of a dissected man,” completed in 1651. Editor: The starkness hits me first. It's brutally direct. The lines are so sharp, so relentlessly focused on the musculature...there's something unnerving but compelling in this exposure. Curator: Yes, the etching method employed would have required immense control. Think about the labor, the press, the copper plate painstakingly etched with acid to achieve such detail. The production itself, born from material investigation, almost mirrors the anatomical examination within the print. The rise of anatomical theaters in the 17th Century encouraged a broader exploration of the body. Editor: Absolutely, and consider how that plays with visual culture. Skulls, bones, exposed muscle: These were potent symbols then, reminders of mortality but also invitations to look deeper, to understand our shared human fragility, and the power such symbols could hold in art and life. The open mouth, the visible sinews, all are like an open book. It invites interpretation. Curator: Hollar created this around the time he came to England from Prague to work as an engraver. Prints democratized knowledge. Disseminating anatomical illustrations like these shifted how information about the human body circulated, enabling a growing audience beyond elite medical circles to engage with it. His London years involved large commissioned works alongside independent art creation. Editor: And you see echoes of the 'memento mori' tradition, the constant presence of death, right? This image is not merely scientific, but deeply symbolic. Think of how we imbue skeletons even now with specific meanings, sometimes comical, sometimes deeply philosophical. Curator: It reminds us, the making is intertwined with its purpose, it has been through material practice that Hollar communicated knowledge across temporal and cultural barriers, connecting the world of science and labor, with symbolism. Editor: Ultimately, it's a reminder of our complex relationship with imagery: how images carry meaning, change across time, yet still connect us to shared, core human experiences. It makes us think. Curator: Precisely. Thinking, creating, knowledge production, its all here and available across the centuries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.