painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

sculpture

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

lady

#

charcoal

#

statue

#

christ

Dimensions: 101.2 x 43.7 cm

Copyright: Public domain

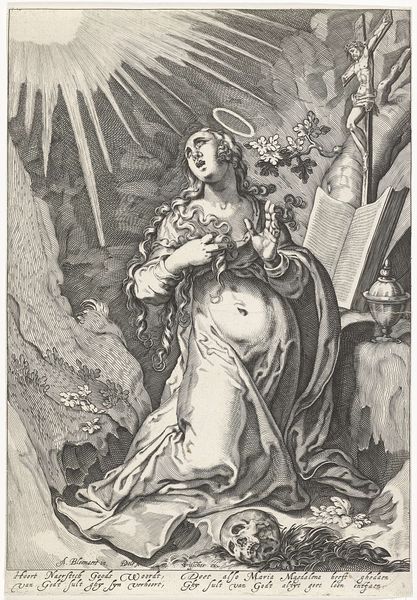

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the sheer softness of this work, like looking at a charcoal drawing that's threatening to smudge if you breathe too close. There’s an almost photographic quality in the gradations of tone. Editor: Yes, Matthias Grünewald's "St. Lucy," painted around 1511, possesses that delicate balance. It's oil paint, surprisingly, and while seemingly monochromatic, the subtlety suggests incredible skill, especially considering the limitations of the medium. It represents St. Lucy, martyred for her Christian faith in the early 4th century. Curator: "Softness" isn't quite the right word – maybe ethereal is better. Like she's about to fade into the architecture around her, dissolve back into the spiritual realm. Is that intentional, I wonder, a way of depicting her sanctity? Editor: I think you’re onto something there. The composition and setting elevate her status. Enclosed in what appears to be a painted architectural niche, we're meant to view her as set apart. This isolation emphasizes Lucy’s devotion against the turbulent backdrop of the early church and, perhaps, Grünewald’s own fraught historical context. The painting presents the public role of the image: not merely to depict, but to instruct in faith and inspire piety in civic space. Curator: The plant she holds... It feels very particular. What is that? I sense a kind of visual language that I can't quite decipher. Editor: That would be a palm frond, which traditionally symbolizes victory and martyrdom in Christian art. St. Lucy is commonly depicted with it, recognizing her triumph over persecution. In a symbolic sense, St. Lucy’s presence among us becomes a bridge connecting humanity to the sacred, allowing the possibility of grace, not just recalling historical and spiritual forces, in order to help guide how we look back at the past and see where the world's current moral and socio-political compass came from. Curator: I see it. Thank you! You know, standing here, I sense a connection to her unwavering beliefs. There's power here; it almost makes you want to reach out to feel the layers of her conviction. The visual rhetoric makes this historic martyrdom very real. Editor: Precisely, art holds this power to draw out truths—emotional, historical, spiritual—and perhaps to make the past a vivid force that moves the present. It's an intriguing painting; Grünewald manages to find beauty in the sombre aspects of Christian spirituality, connecting audiences with this iconic martyr, which helps reinforce and shape cultural memory in very public and communal contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.