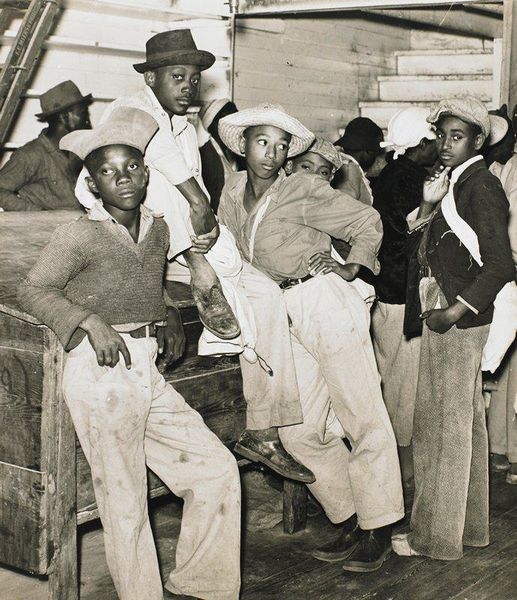

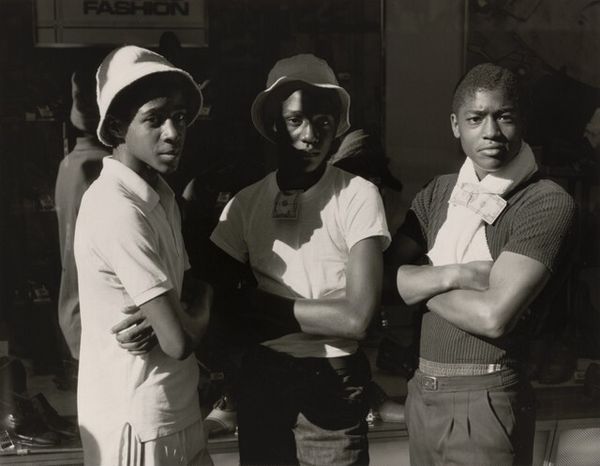

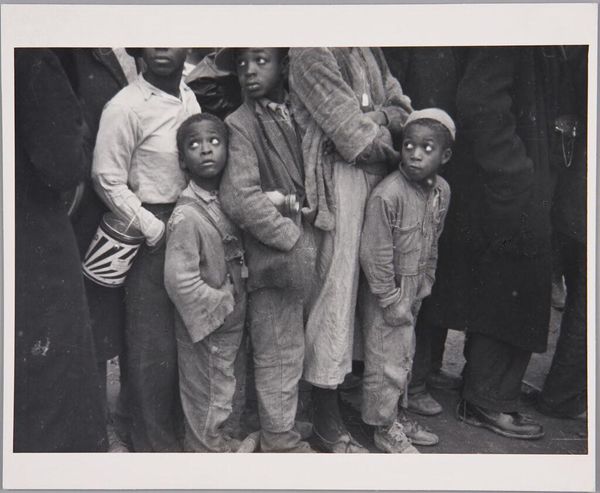

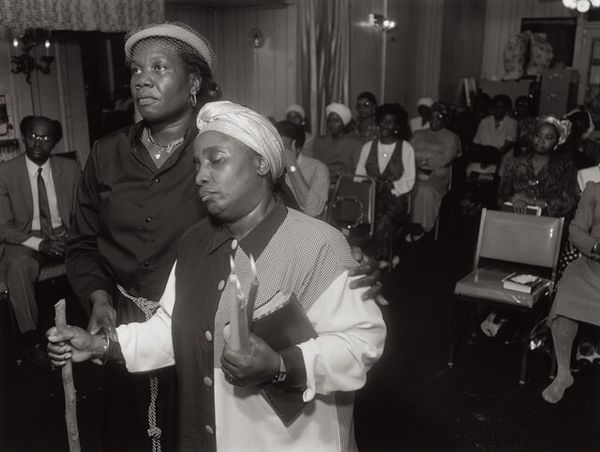

photography, gelatin-silver-print

african-art

black and white photography

social-realism

street-photography

photography

historical photography

group-portraits

black and white

gelatin-silver-print

monochrome photography

genre-painting

monochrome

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet: 50.8 × 40.48 cm (20 × 15 15/16 in.) image: 43.18 × 37.94 cm (17 × 14 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

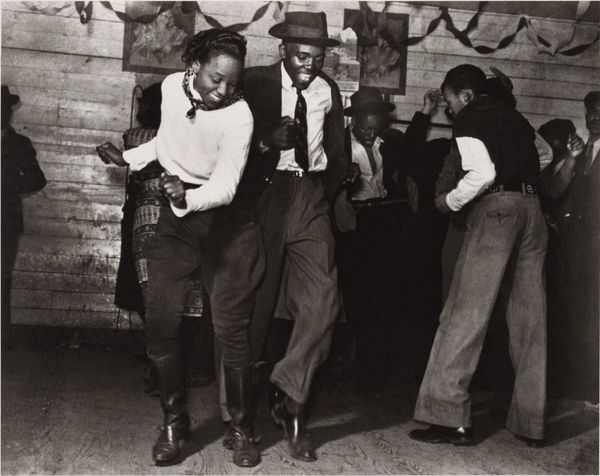

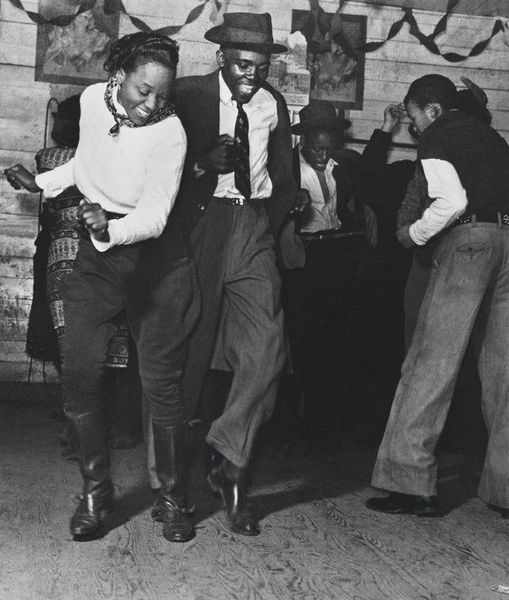

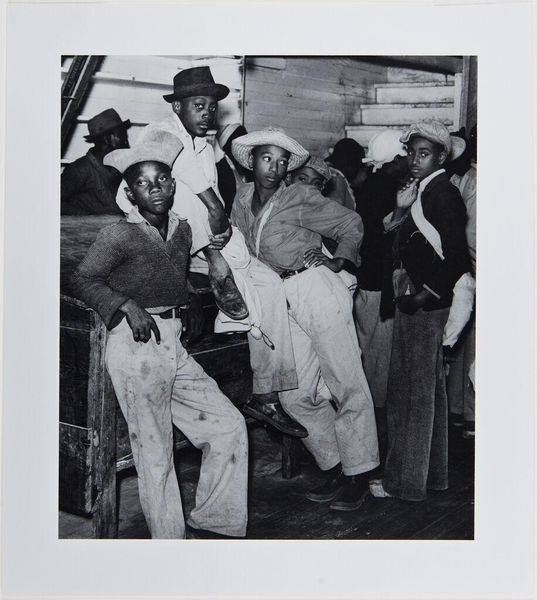

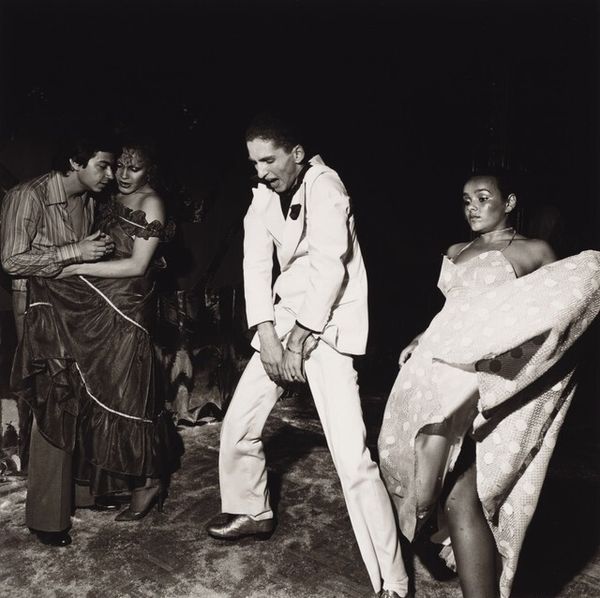

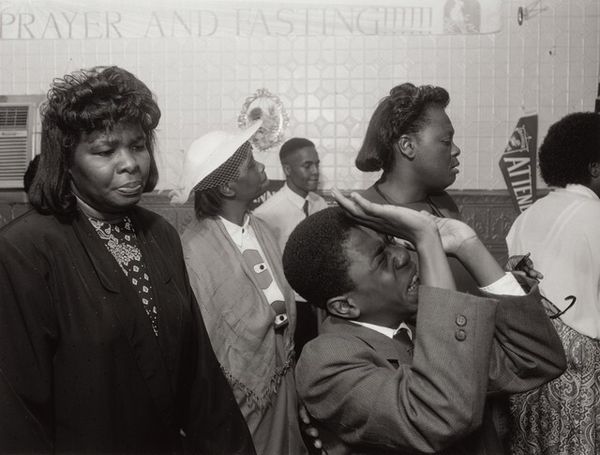

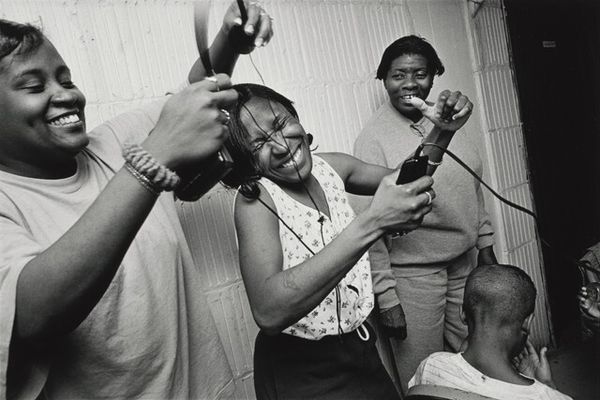

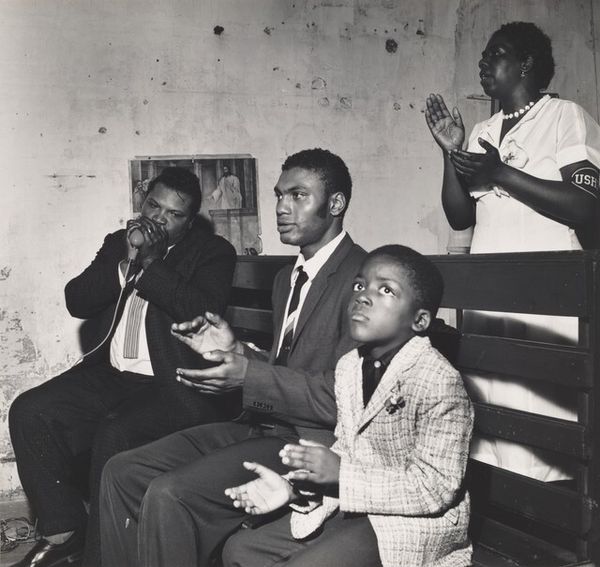

Curator: This compelling photograph, taken by Constance Stuart Larrabee after 1948, depicts a social center in Johannesburg, South Africa. It’s a gelatin silver print capturing a lively dance. The image provides a glimpse into Black social life during the apartheid era. Editor: My immediate impression is one of dynamic movement. The stark monochrome palette emphasizes the contrast between light and shadow, really highlighting the energy of the dancing figures and worn textures of the floorboards. Curator: Indeed. Consider that this was taken in the early years of apartheid, and how the act of joyful gathering itself becomes an act of resistance and self-affirmation. Larrabee, though a white photographer, offers us a rare, intimate view of a space where Black South Africans could express themselves freely. Editor: I agree. The material aspect, though simple, contributes so much. Gelatin silver printing, with its capacity for sharp details and rich tonality, becomes a crucial tool to document social realities. And the very act of taking these photographs had material consequence. How were these images circulated, consumed, and interpreted in that context? Curator: The distribution would have been limited within South Africa due to censorship. But internationally, photographs like this were crucial in shaping global awareness of the injustice of apartheid and galvanizing support for the anti-apartheid movement. Editor: Absolutely. The image feels almost ethnographic, offering a lens into specific practices—dancing, dress, interaction—that defined this community space. Look at the well-worn hats and tailored clothes; clearly care and consideration were given to appearance within a segregated society. The image's construction tells us how these citizens used creativity and performance to assert their culture, despite social pressures. Curator: I'm also drawn to the gaze of several figures. The woman looking directly out, challenging the viewer. Does that gaze alter the ethics and politics around bearing witness? Her gaze complicates any easy reading of the image. She becomes both the subject and object of representation. Editor: Exactly. It raises critical questions about labor, image production and distribution. We see evidence that despite adversity, joyful acts such as these represent labor; both social and communal. Curator: So while this image documents a specific moment, it resonates with larger narratives of identity, resistance, and representation. Its very existence speaks to the power of photography to bear witness to history. Editor: The tangible feel of the gelatin silver print, the contrast, and the sharp focus—all emphasize the physical conditions of both production and consumption. In other words, the photograph underscores both the making and the means through which images were engaged. It's more than a snapshot; it’s material evidence of both creative endeavor and community resilience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.