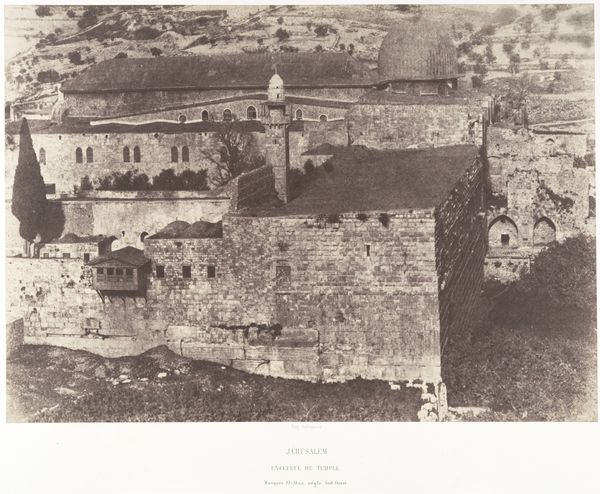

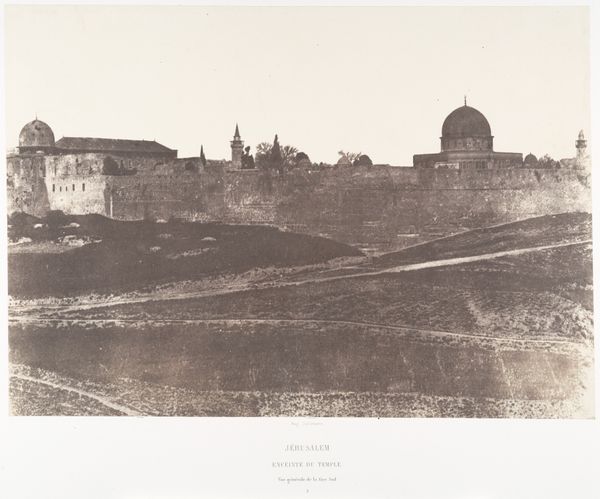

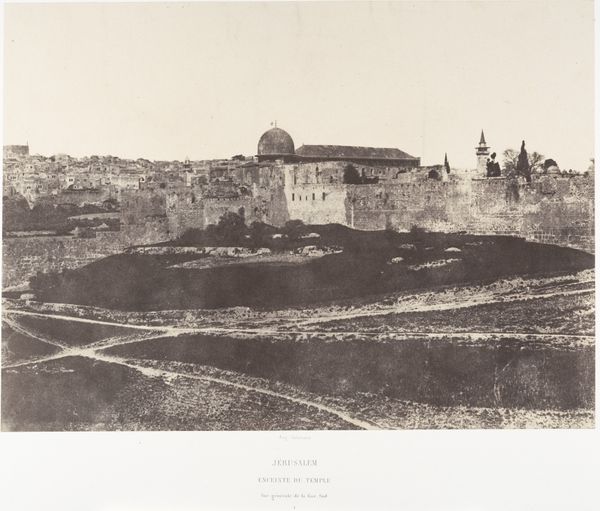

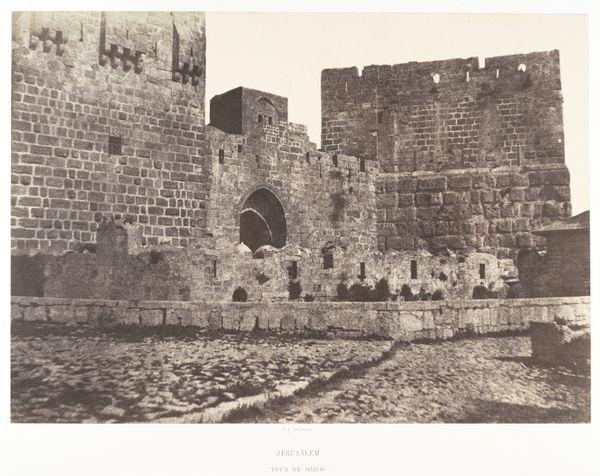

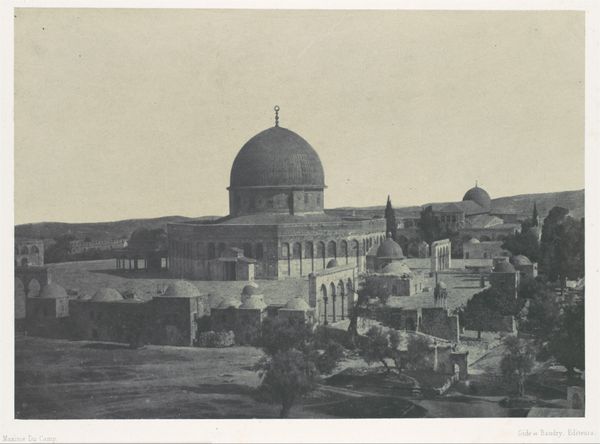

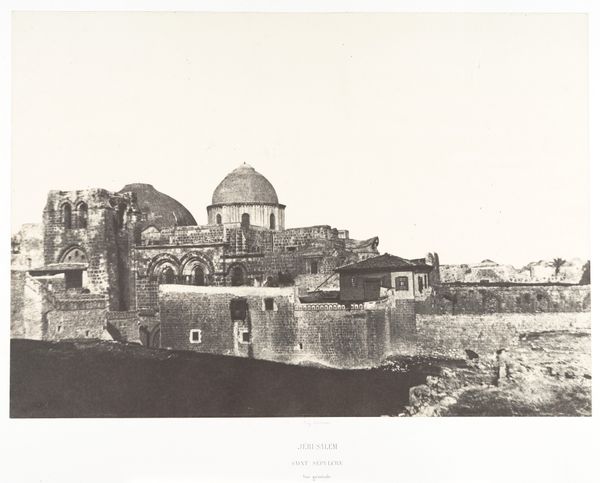

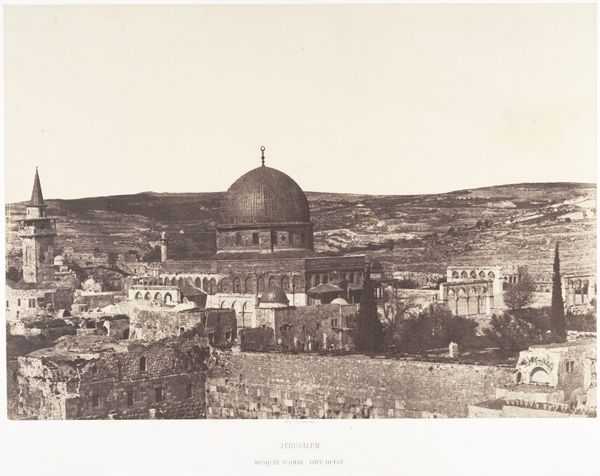

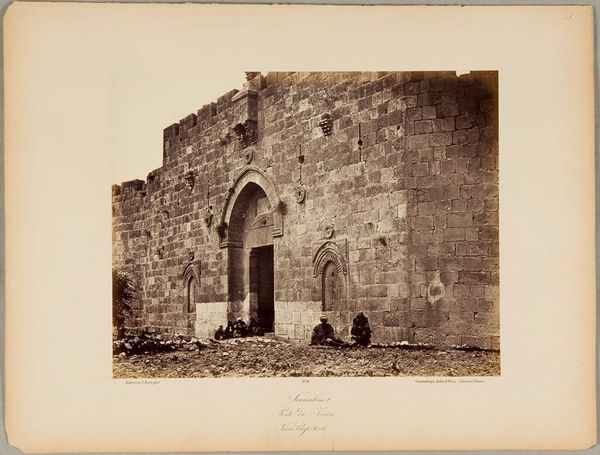

Jérusalem, Enceinte du Temple, Face sud de l'angle Sud-Est 1854 - 1859

0:00

0:00

print, photography, architecture

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

arch

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 23.3 x 32.8 cm (9 3/16 x 12 15/16 in.) Mount: 44.7 x 60.5 cm (17 5/8 x 23 13/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

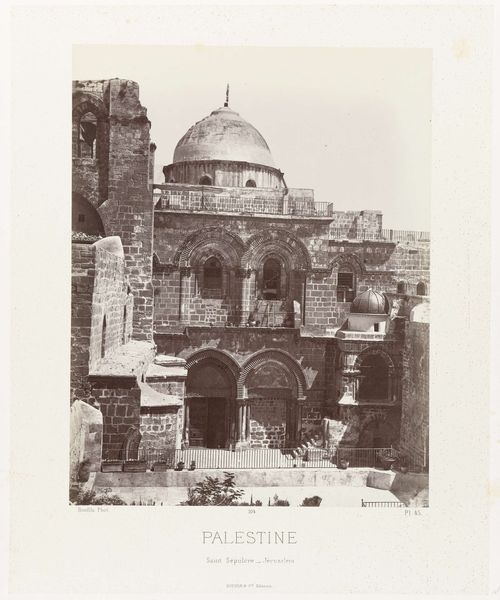

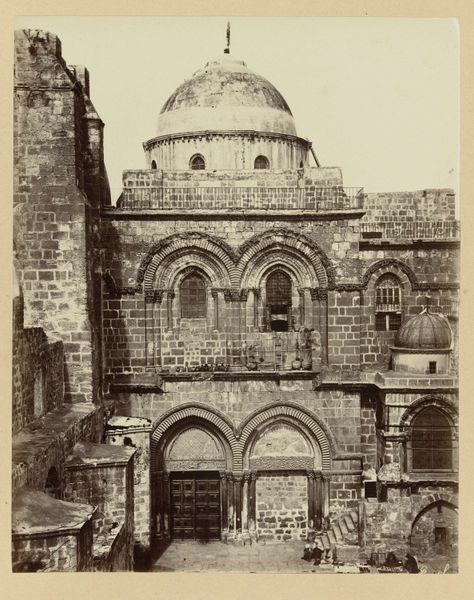

Curator: Auguste Salzmann’s photograph, taken sometime between 1854 and 1859, presents us with the south-eastern face of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. It's an early example of photography used for documentation, isn't it? Editor: My immediate impression is one of weight – a density of stone pressing down. The tonal range is narrow, and the lack of vibrant color intensifies the somber feel. It’s a picture of a built environment asserting its dominance. Curator: Absolutely. I find myself contemplating how the very act of Salzmann pointing his lens transformed a holy site into a study of geology, texture and labor. Each stone laid by a pair of hands is rendered, by a different kind of hand—the artist’s. The photographic process is not dissimilar, you know, it processes light to create images. Editor: Exactly! And think of the social context – mid-19th century, rising colonial interests, and the fascination with archaeological discoveries. This isn’t just a landscape; it’s a carefully constructed representation loaded with political implications, down to the cost of albumen paper he uses! How interesting that Salzmann also explored the biblical record alongside making a document. Curator: It certainly encourages a critical reading, doesn’t it? Though, I do get a deep sense of solitude. Even if unintended by Salzmann, a meditative and reflective aura radiates from it, reminding us of the enduring spirit of place. Almost feels… haunted by history, you might say? Editor: Haunted indeed – haunted by the marks of human toil! Those weathered stones tell a story not just of faith but of exploitation, extraction, and empires clashing. I imagine the quarry workers, the builders, the communities displaced or taxed to realize such grand designs. What did Jerusalem mean to the colonizing imagination, and the cost of image making in the nineteenth century? Curator: I see your point. The photograph does act as a register of material and a record of control as well. That is why a return to the image yields different insights. I may dream of wandering within that ancient city, while another sees, feels and experiences its troubled origins, right? Editor: Precisely. I suppose we are both left with something profound, yet strikingly disparate to take away with us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.