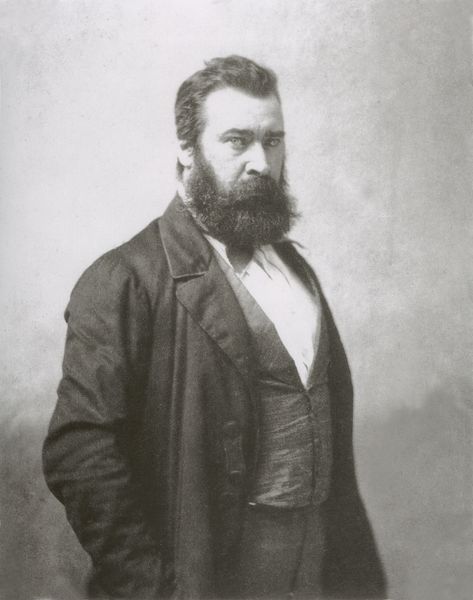

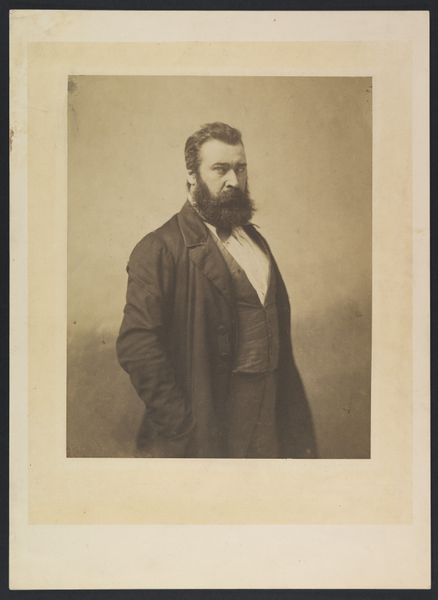

Copyright: Public Domain

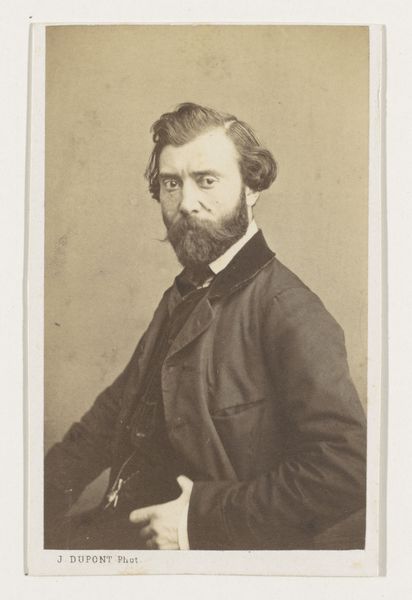

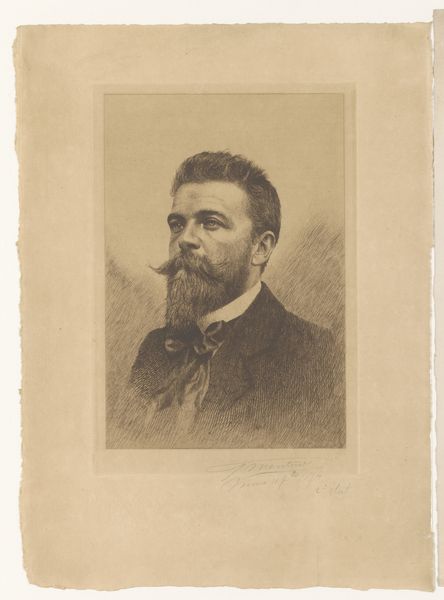

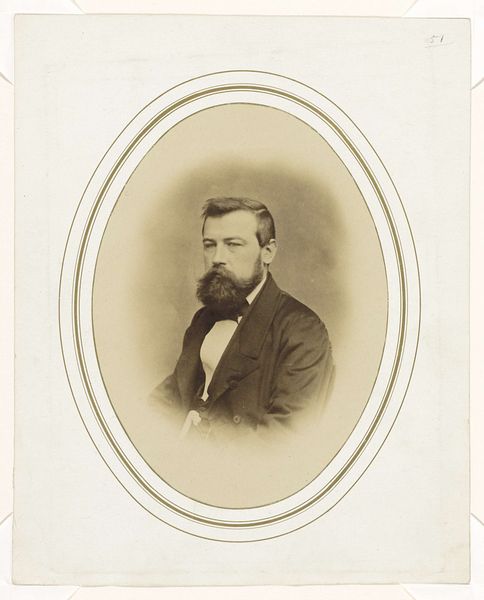

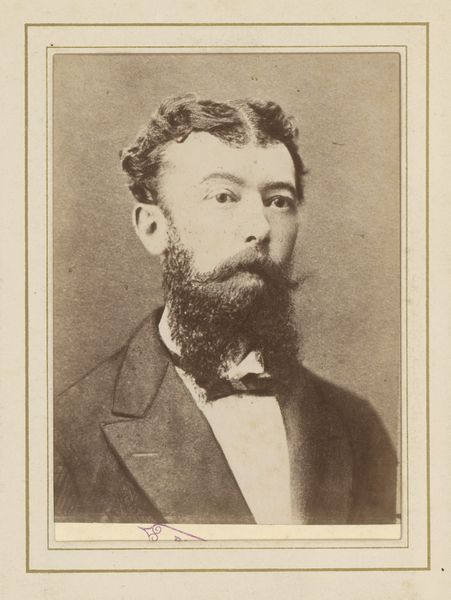

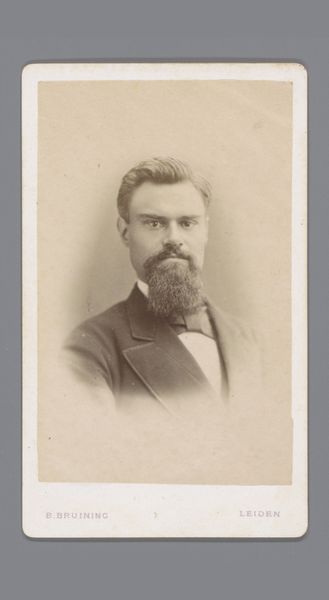

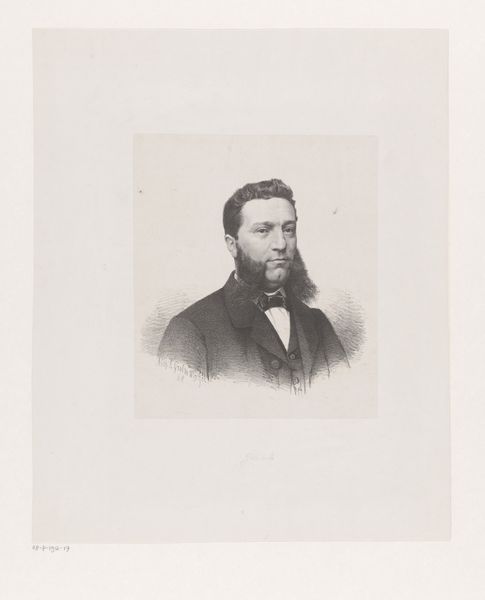

Editor: This is Nadar’s photograph of Jean-François Millet, a gelatin silver print from around 1856 to 1858. It's a very direct portrait. What strikes me most is the intensity in Millet's eyes, it feels very…present. How do you interpret this work? Curator: That intensity speaks volumes, doesn't it? But let's unpack it. Nadar wasn't simply capturing a likeness; he was constructing an image of a man deeply connected to the land and to his labor. Consider Millet’s politics: his paintings often depicted rural life, highlighting the dignity—and sometimes, the struggles—of peasants at a time when industrialization was drastically reshaping French society. Do you think Nadar’s portrait resonates with these themes? Editor: Absolutely, there’s a grounded quality to him, even in a studio portrait. I see what you mean. Was Nadar also interested in the politics of labor? Curator: Precisely! Nadar was a radical himself, a staunch republican. This portrait is a deliberate act of elevating Millet, a painter who dared to depict the working class with respect. By photographing Millet, Nadar wasn't just documenting an artist; he was aligning himself with Millet’s artistic and political vision. Think about the act of portraiture itself – who gets their image preserved, and why? This image challenges the conventions of the time. Editor: So, the photograph is an assertion of Millet’s importance and the value of the subjects he painted? Curator: Exactly! And more broadly, it asks us to consider who gets to be seen, who gets to be remembered, and what stories we choose to tell. It’s a question that still resonates powerfully today. Editor: I never thought of it that way before. It’s like the photograph itself is taking a stand. Curator: Indeed. And that’s where art history meets activism, inviting us to see beyond the surface and engage with the deeper currents of power and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.