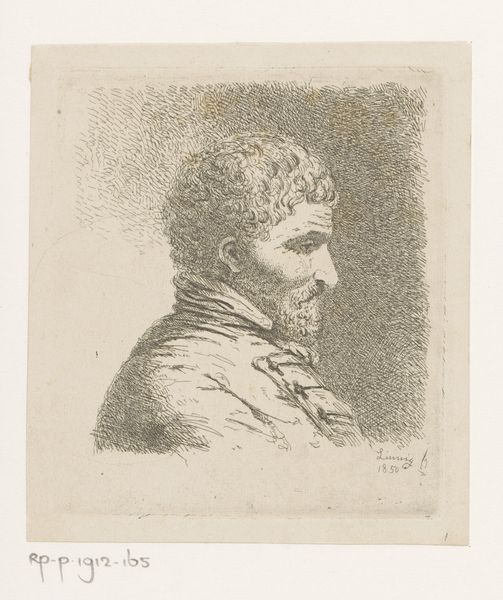

drawing, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

realism

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 65 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

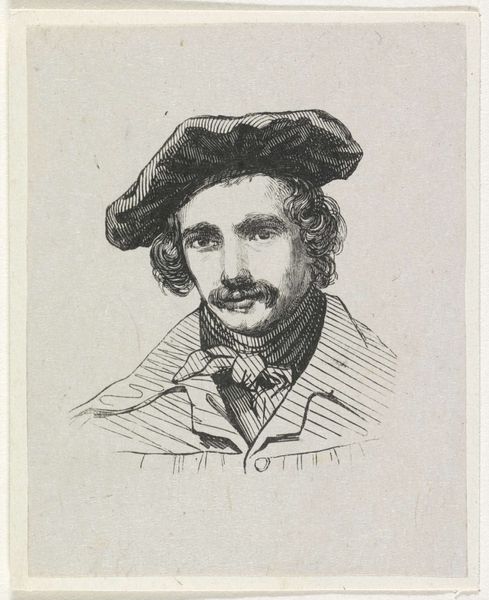

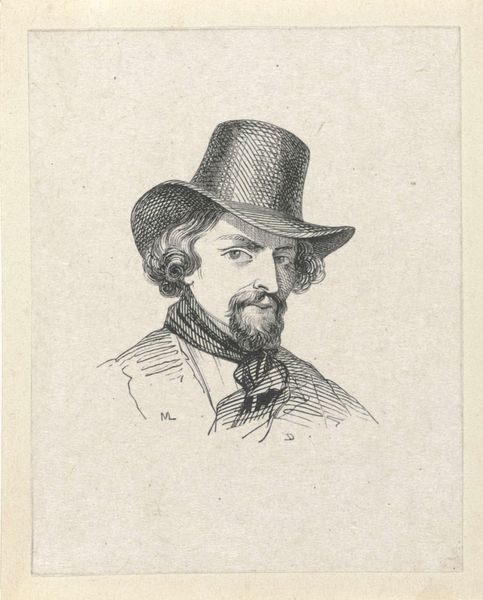

Curator: Here we have a work entitled "Bust of a Man," crafted by Kornelis Jzn de Wijs in 1854 using graphite and pencil. Editor: The hatching! Immediately striking. So dense it almost veils the subject in shadow. What emotions does it evoke? A sense of age, perhaps, or even some kind of social hardship. Curator: Indeed. Notice how the dense linework emphasizes the contours of the face, creating a pronounced texture, especially around the eyes and mouth. Observe, too, the way the background hatching remains detached from the figure. It’s less concerned with accurate lighting, it seems, and more with delineating pure shape. Editor: Precisely. Think about who this man might have been within his socio-economic reality, if it can be assessed solely by looking at his appearance. Is he a working-class citizen or possibly some more educated individual? And think how portraits of individuals like this serve to include those who may not historically have been well-documented. Curator: Good point, and this moves us toward understanding De Wijs' aims as a Realist artist during that particular period. As you observe, "Bust of a Man" could have indeed been conceived with the goal to bring these individuals closer to the awareness of the academic elites. Consider the patterned jacket; the tight hatching captures a textural quality but does not provide further socio-historical information regarding his possible belonging to a group or a movement. The form appears more symbolic of general economic stratification. Editor: What does it signal in terms of artistic access? Was it more feasible to do a portrait like this compared to an oil painting, let's say? And were similar pencil sketches produced on the scale we may expect to see today, if someone sets up to take a sketch in public? Curator: The drawing is small, probably created with intimate study as the only real constraint, so this fits with how Realist artistic approaches evolved within different historical landscapes. As you know, with photography coming into being as an instrument of record, painters found themselves freer to produce work of an increasingly documentary nature. Editor: Overall, despite what could be conceived of the melancholy face captured here, it has given us some insight into ways we may be closer to individuals lost in time due to how art approaches the human condition and captures faces like these. Curator: I would say so. I have certainly been drawn into reconsidering the relationship between realist aesthetics and social observation within art institutions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.