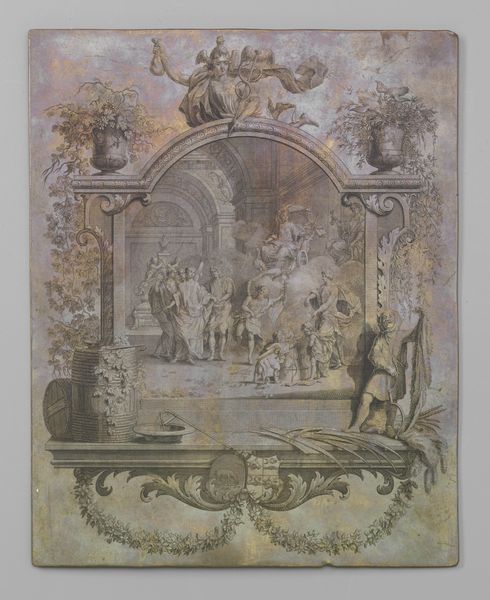

engraving

#

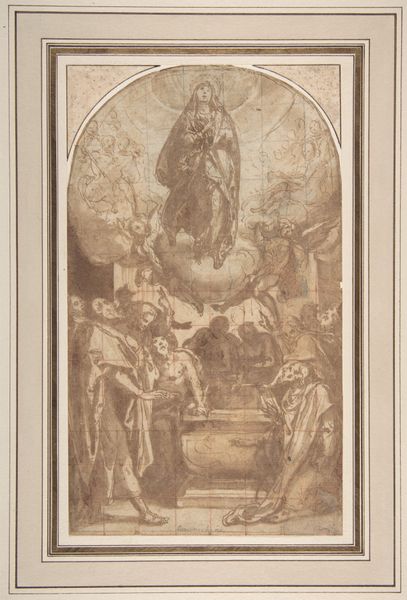

portrait

#

allegory

#

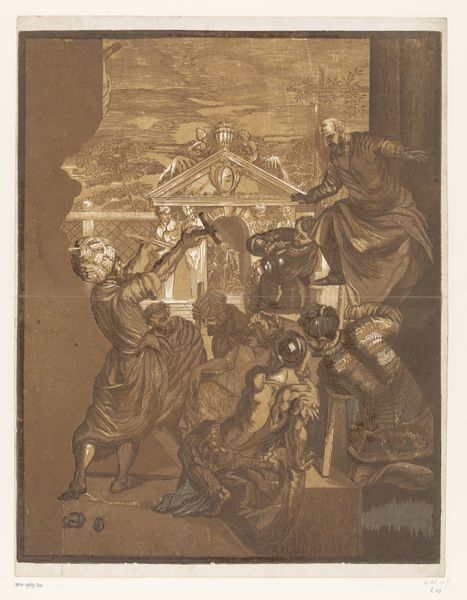

baroque

#

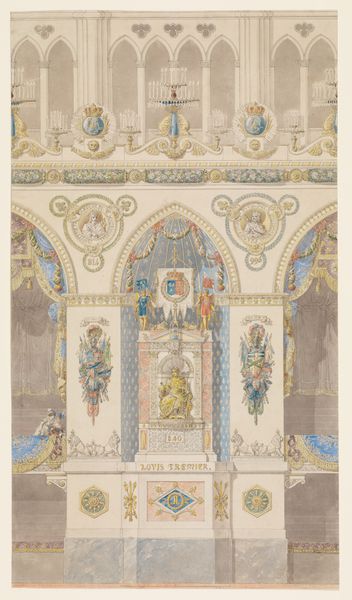

coloured pencil

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 193 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

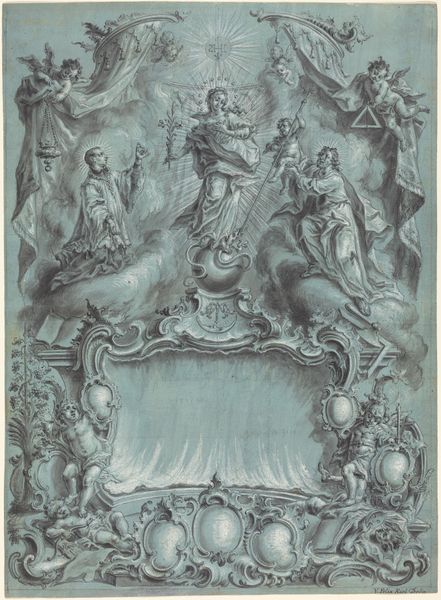

Curator: Here we have "Huwelijksportret," or "Marriage Portrait," an engraving crafted sometime between 1663 and 1683 by Romeyn de Hooghe, now housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has this very aged look, almost like aged parchment. The image is quite stylized. I wonder, what was involved in this type of engraving? Curator: As an engraving, the creation involved cutting lines into a metal plate, likely copper, which would then be inked and printed. The result allowed for relatively mass-produced images to spread ideas and depict status. I find the composition here particularly compelling: we have what appears to be a bride and groom standing at the altar with classical detailing, their clasped hands symbolizing the binding of their lives. Editor: There's something unsettling in the lack of intimacy. Their attire feels almost performative, draped. The etching highlights their societal roles and perhaps conceals a darker power dynamic. We’re also given only a limited depth of space. Curator: Absolutely, this aligns with much baroque art, where display of status, wealth, and lineage became quite fashionable. You can see each of them is flanked by a column holding up dark curtains with heraldic markings that reinforce the societal significance of this union. But, of course, you can't overlook the political element! In these unions, marriages were, so often, as much about securing power or capital. Editor: Indeed, the medium mirrors the message. I wonder how those plates aged, the work involved and even the smells present in these studios would have communicated labor involved. In thinking about production of the material it really pushes us to question how labor and resources were viewed by a culture that then consumed such imagery so widely. Curator: Considering its reception broadens our view, right? Did viewers scrutinize or blindly accept these narratives? Did women recognize or resist its depiction of their limited agency, in reality? I suspect that looking more closely could reveal a silent dialogue between visibility, privilege, and exploitation. Editor: Right. It makes me think deeply about not just what we are seeing, but who has traditionally had access to artmaking and who is included or excluded through material practices. Curator: So true! Thank you for providing such necessary context as we continue our critical view of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.