#

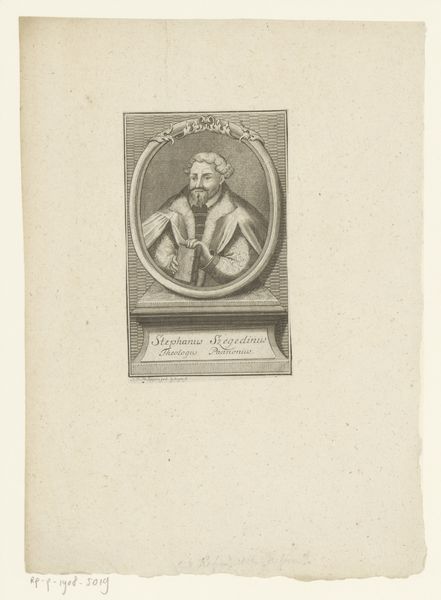

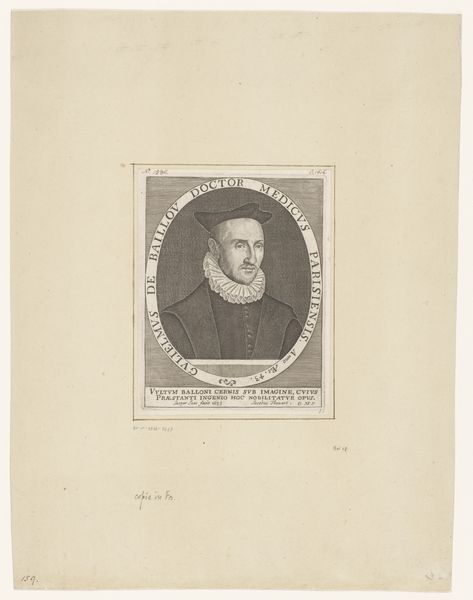

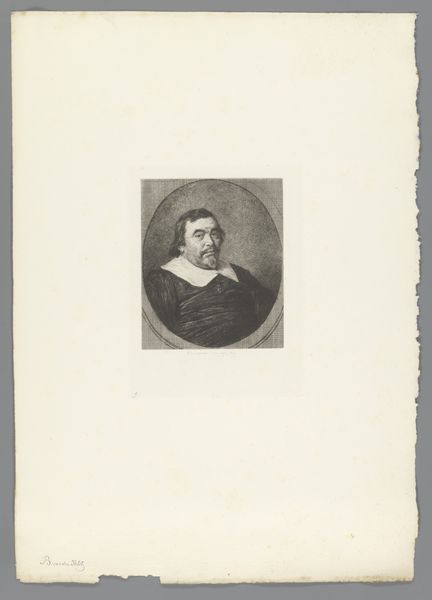

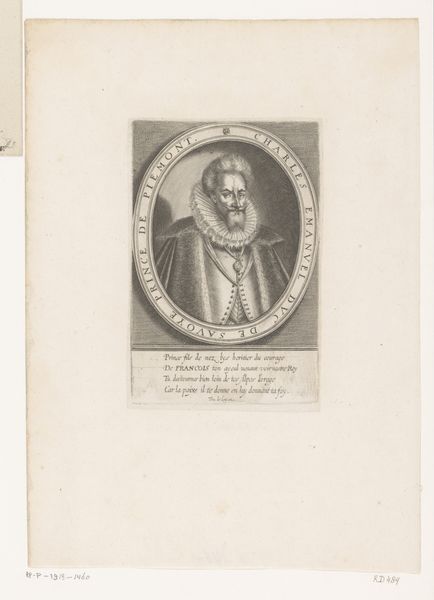

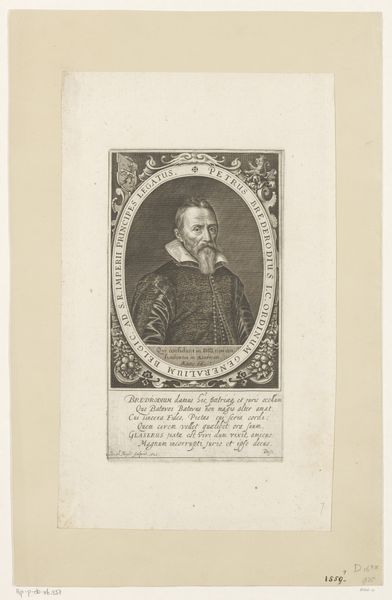

photo of handprinted image

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

muted colour palette

#

photo restoration

#

parchment

#

old engraving style

#

retro 'vintage design

#

personal sketchbook

Dimensions: height 139 mm, width 104 mm, height 433 mm, width 278 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

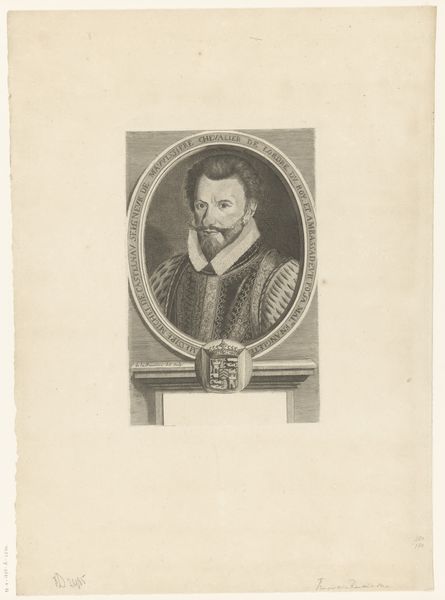

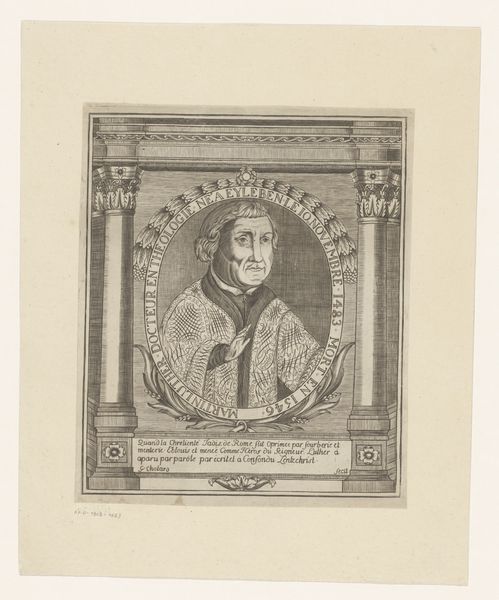

Curator: This portrait, etched in 1621 by Lucas Kilian, depicts Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg. What do you make of it? Editor: My first thought? Stern. Very official. And... airless, somehow. Like a specimen pinned under glass, yet, maybe I’m drawn to this intense feeling? Curator: Kilian was part of a printmaking dynasty; they really understood how to disseminate images of power and influence. Look at the framing, the Latin inscription circling Hoë’s portrait, lending authority and proclaiming his virtues. This wasn't just a likeness; it was a statement. Editor: Right. You see the mechanics, I guess. I'm more struck by the way light seems trapped *within* the face. It's an amazing, almost haunting contrast between his sharply etched features and the surrounding formality. It makes me consider, "Who was this man, behind this official look?" Curator: Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg was no ordinary man. A leading Lutheran theologian, advisor to princes, and a central figure in the religious and political landscape of the Holy Roman Empire, which also explains the care Kilian took in his portrait. Images held immense weight. Editor: Still, even knowing his stature, there’s a quiet unease emanating. I feel I’m getting an intriguing glimpse behind the propaganda, which adds another fascinating layer. Don't you think this is part of why we’re so drawn to old portraiture in the first place, trying to decode this sense? Curator: Precisely. We bring our modern eyes to an image intended for a completely different audience and time, resulting in these multilayered interactions that invite reflection, dialogue, and sometimes a little speculation. Editor: A reminder, too, that art isn't created in a vacuum. Political, social, and spiritual forces were at play in 1621. To truly "see" this artwork, we must at least glance at the era and its people. It shifts the whole reading... and deepens it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.