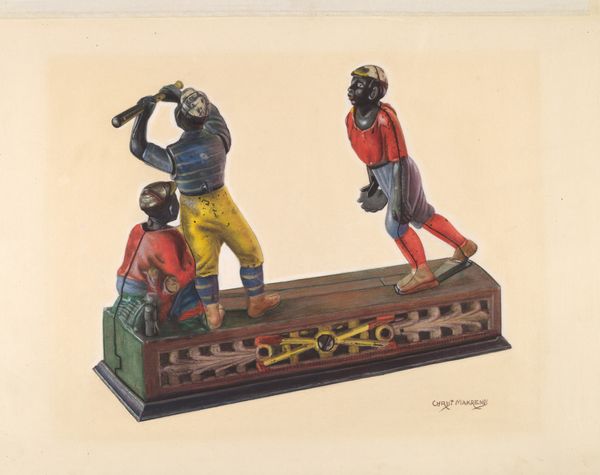

drawing, coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

caricature

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

folk-art

#

portrait drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

modernism

Dimensions: overall: 22 x 30 cm (8 11/16 x 11 13/16 in.) Original IAD Object: 7" high; 10" long; 2 3/4" wide

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: The piece we're looking at is called "Toy Bank," believed to be created around 1938 by Ethel Clarke. It's rendered using drawing and colored pencil, heightened with watercolor. My first impression? It's a startling piece, immediately invoking a troubling history. Editor: Startling indeed. The imagery is…difficult. There's a visual tension between the playful medium, like those vibrant colored pencils, and the unsettling caricature depicted. Curator: Precisely. The artwork portrays what appears to be a cast iron mechanical bank, featuring overtly racialized caricatures of African Americans engaged in a baseball scene. "Darktown Battery," the inscription on the base, explicitly references a deeply problematic and stereotypical representation. The exaggerated features, the attire, and the very name are all laden with historical baggage. Editor: It's disturbing how such harmful images were once normalized and even marketed to children as toys. Looking at the way Clarke uses color, I almost sense an attempt to… soften the blow, perhaps? Yet the very existence of this kind of artifact in the 1930s reveals a complex commentary about American social attitudes. Were there people at that time who realized what a distortion of truth this type of art represents? How might such a piece impact people's views? Curator: That's where it gets even more layered. On one level, it’s a reflection of prevailing racist imagery perpetuated through popular culture and commercial goods. On another level, and recognizing Clarke’s potential positionality as the artist, we could read it as an unsettling critique. Highlighting this object might underscore its inherent grotesqueness and prompt viewers to confront the roots of systemic racism. Is she holding a mirror up to racism through satire? Or is she perpetuating the bias in her art? Editor: So the act of depiction becomes a form of uncomfortable archive—a way to force a dialogue on deeply ingrained prejudice by showing it? Curator: Possibly. Considering folk-art’s complicated legacy as an instrument for perpetuating prejudice and reflecting it, we have to ask whether reproducing such iconography, even within the safe context of artistic intention, opens the way for reinforcing it again? Can art like this change views by confronting an injustice directly? Editor: Looking closely at it, the baseball motif also feels like a critical point. Given baseball's significance in African American culture—especially in the face of exclusion from mainstream leagues at that time—the portrayal here gains added meaning, layering sports history and socio-political circumstances onto one artwork. The team that this artwork refers to, The Cuban Giants, a Black professional baseball team, had their start in 1885, by playing using pseudonyms like ‘Philadelphia Pythians’, ‘Manhattan Athletics’, ‘Argyle Hotel Stars.’ Their need to hide their identity indicates that prejudice impacted not only sport but all societal functions. Curator: A striking thought! This colored pencil sketch invites crucial conversations. I think exploring this historical and socio-political narrative allows one to grapple with an important component of intersectionality and race representation and the politics of imagery. Editor: Absolutely. Recognizing the historical context is important as it shapes not only the artwork's inception but also its enduring, provocative power to generate vital discourse around historical attitudes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.