photography

#

still-life-photography

#

landscape

#

photography

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

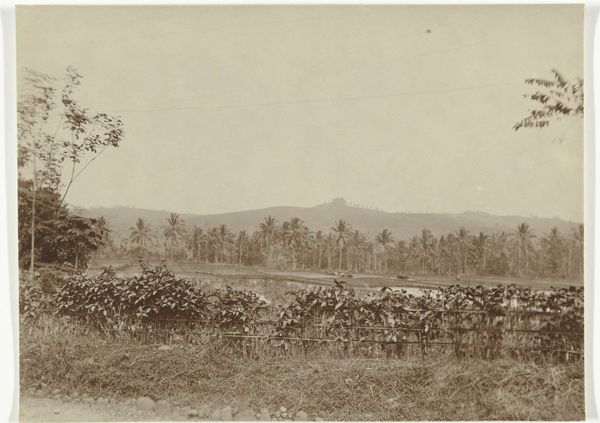

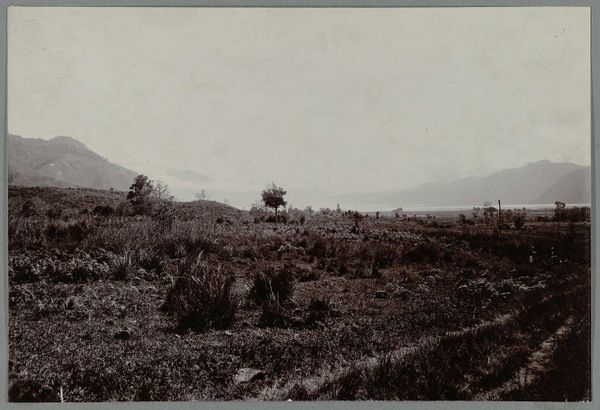

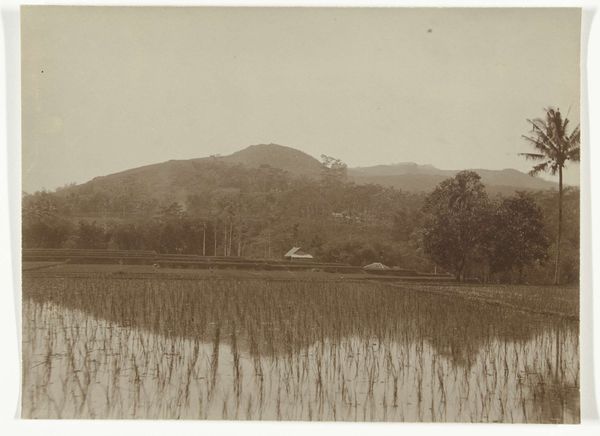

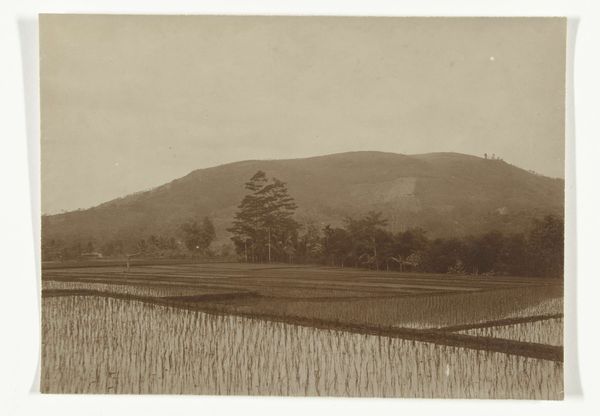

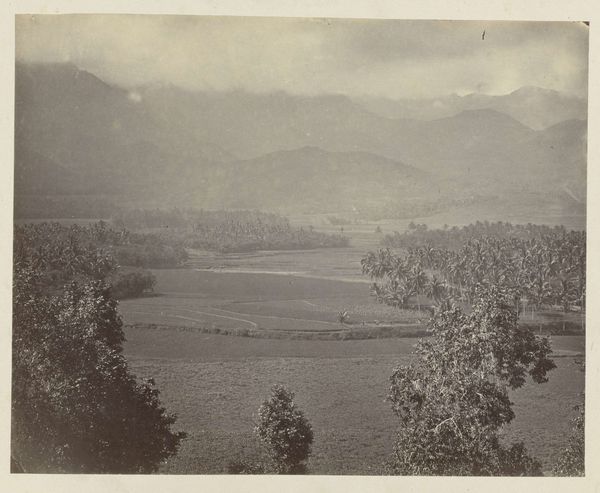

Curator: I’m drawn to the way this anonymous photograph, “Plantage,” taken sometime between 1903 and 1913, presents the landscape. It feels vast and intimate all at once. Editor: Yes, it’s striking how the field in the foreground, full of what I presume are crops, dominates the composition, almost obscuring the mountains behind it. There's a curious flatness, too. It feels less like a celebration of nature's beauty and more of a…record? Curator: A record of a system, perhaps? I can’t help but see echoes of productivity, of something grown not just for beauty, but for sustenance, or even capital. The monochrome softens any harsh edges though. I find a strange beauty in the monotony. Do you feel it's successful in doing that? Editor: I appreciate your read. The very word 'plantage' whispers of colonialism. I find myself wondering who worked this land, what their lives were like, and how this scene speaks to broader power dynamics of the time. The "anonymous" attribution of the work underscores how entire labour forces could simply disappear from record. There's nothing 'monotonous' to my reading—I find it devastating. Curator: I see what you mean, I had missed that element completely. Even the almost naive, amateurish style contributes to a sense of witnessing something unfiltered, and raw, stripped bare in its lack of artistry and intention. What is visible becomes far less important than what has been omitted by both design and happenstance. Editor: Precisely. That sparseness is itself a testament to the erasure and the systemic forgetting woven into colonial projects. How do we even begin to fill in the blanks? What alternative perspectives should we consult to gain a truer understanding of these historical photographs? Curator: The shadows grow even longer and more complex with this in mind, and those blank spots begin to resemble gaping mouths, demanding narratives beyond those that fit on the face of the image, calling into question everything you believe you may see. Thank you, because it is no longer merely a distant photo for me, it feels alive, pulsing, full of what is seen and unseen. Editor: Indeed, it forces us to confront the uncomfortable silences of history and how we might amplify marginalized voices to understand those periods, those images, with greater clarity and truth.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.