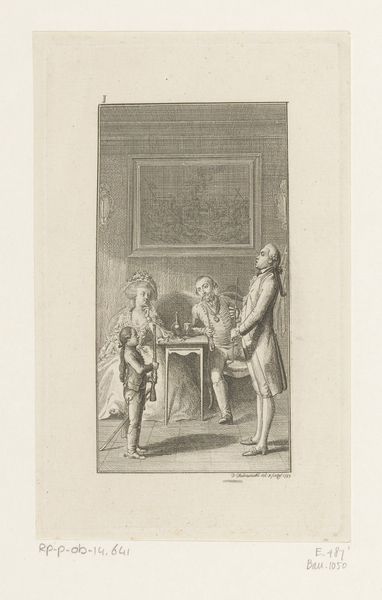

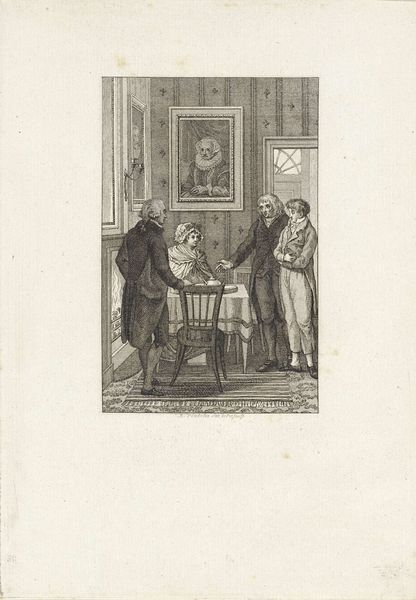

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 103 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

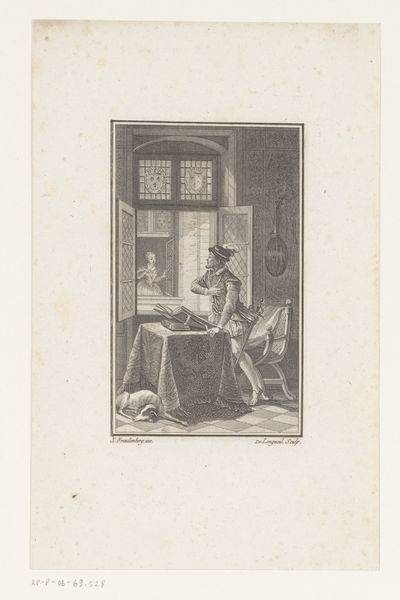

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki's 1784 engraving, "Clarissa en haar onsympathieke vrijer Solmes," or "Clarissa and her Unpleasant Suitor Solmes." Editor: My immediate reaction is how claustrophobic the space feels, despite the relative emptiness of the room. The patterned wallpaper closes in, especially behind the two figures. Curator: Yes, the engraving captures a tense domestic scene. Chodowiecki was very interested in illustrating contemporary literature, reflecting social mores. Clarissa, of course, is caught between societal expectations and her own desires. Editor: And you really see that constraint mirrored in the visual details. The man’s gestures seem to trap her, as do the hard, dark lines of the engraving itself. Was printmaking intended for a wider audience during this time? It almost feels like a narrative unfolding for public consumption. Curator: Absolutely. Engravings like these circulated widely, informing and reinforcing bourgeois values regarding marriage and domestic life. They made art accessible beyond the elite circles. Editor: Considering its method of production and distribution, you also have to see how the material informs the meaning. Each individual line in the engraving is carefully etched, precisely mirroring the social conventions depicted. Do you know the scale of production for something like this? Curator: Estimating exact numbers is difficult, but engravings, unlike paintings, allowed for the creation of multiple impressions. Chodowiecki’s works, popular and widely reproduced, influenced public perceptions and moral standards. Editor: It’s fascinating how such seemingly simple lines could be so powerfully laden with social meaning. It goes far beyond mere representation, offering, instead, a complex artifact imbued with socio-political importance. Curator: Exactly! The act of mass reproduction facilitated a broader conversation around social values. Editor: The more we explore the medium and its context, the more the engraving speaks to not just a moment, but a whole mode of societal discourse, its own peculiar materiality included.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.