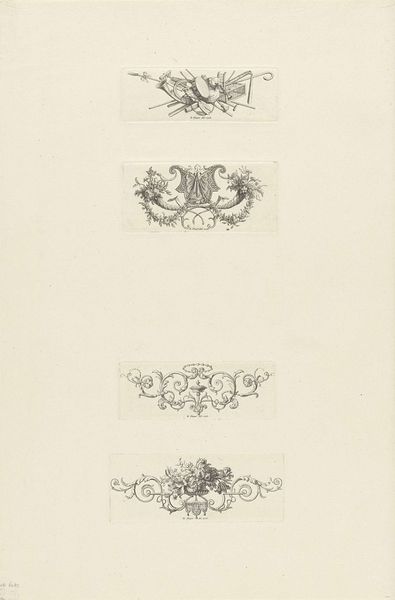

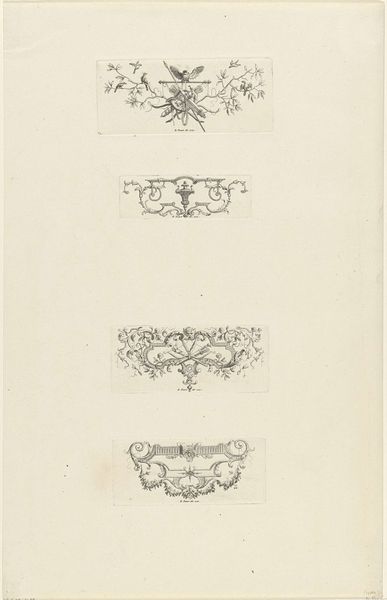

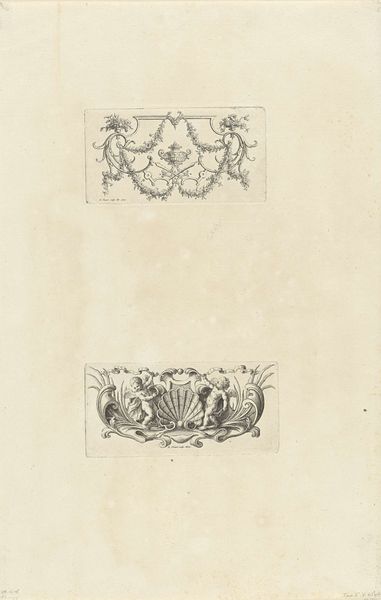

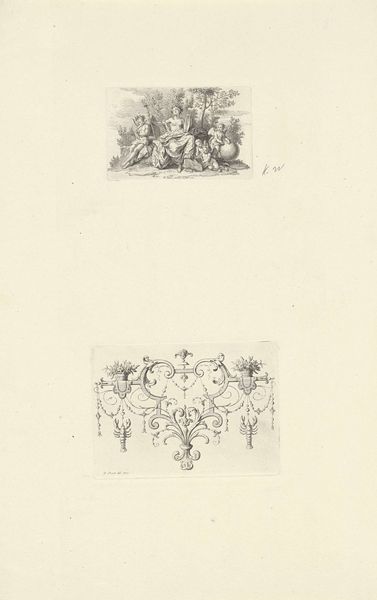

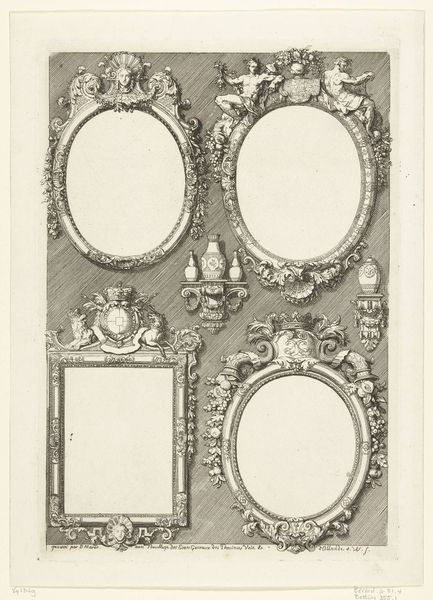

ornament, engraving

#

ornament

#

baroque

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 417 mm, width 266 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

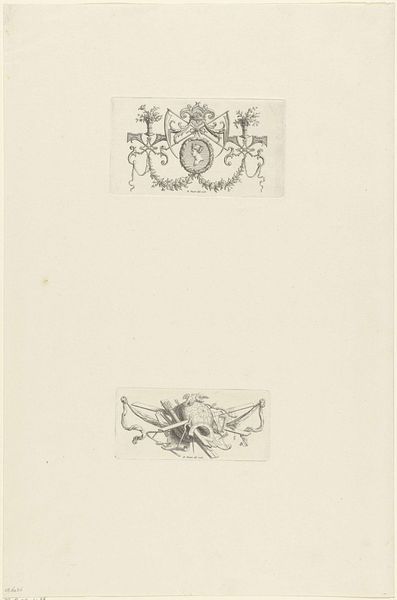

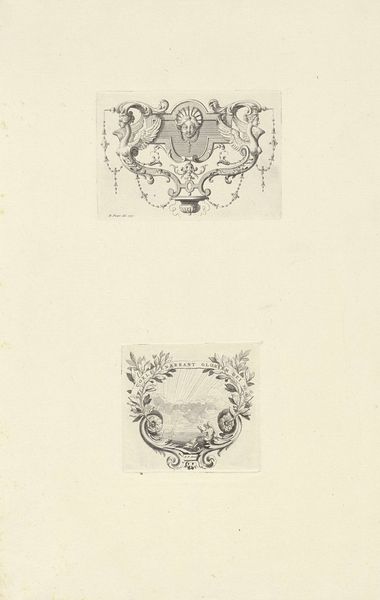

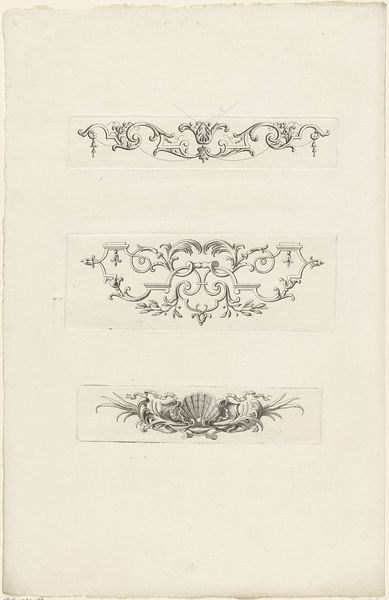

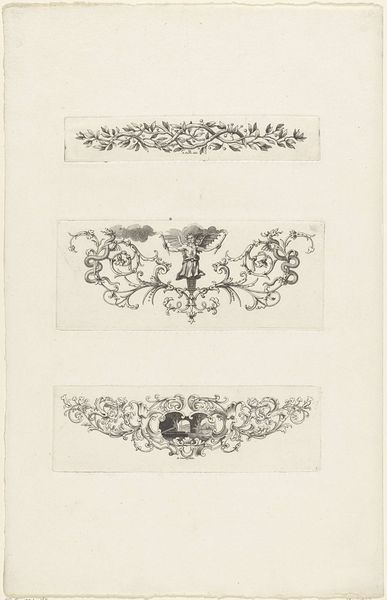

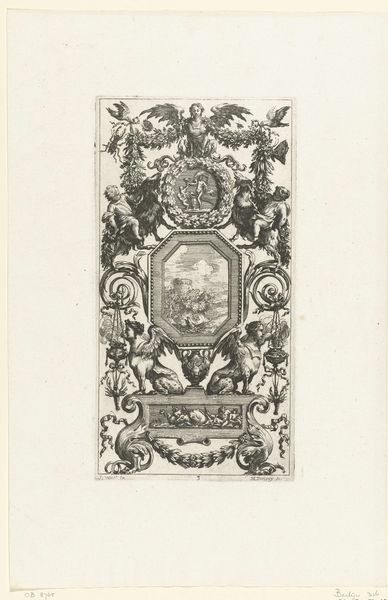

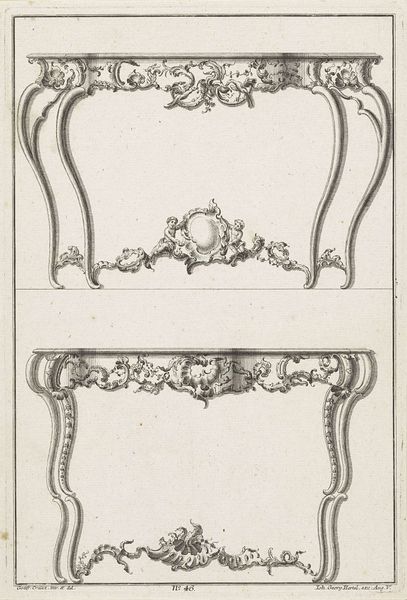

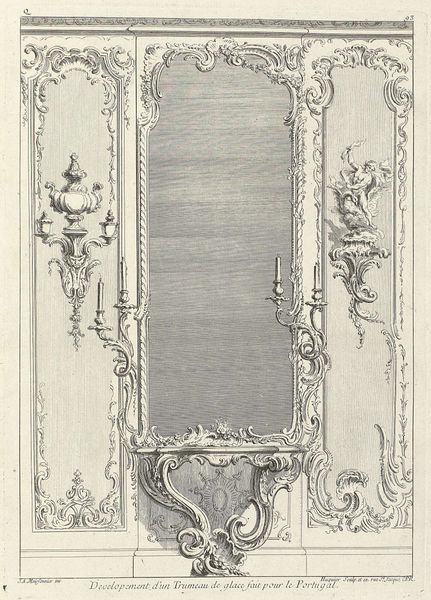

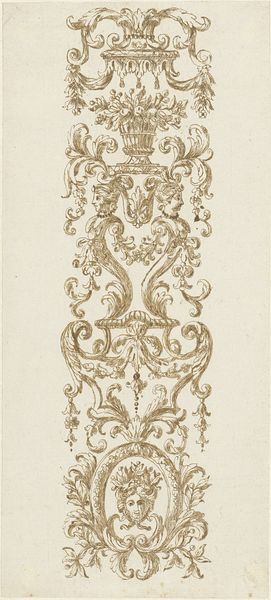

Curator: Up next we have "Vier ornamenten," or "Four Ornaments," an engraving by Bernard Picart dating from around 1727 or 1728, now residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, the meticulous detail strikes me. These feel less like spontaneous flourishes and more like meticulously planned motifs, born of considered labour. Curator: Indeed, these designs were made during a time when printmaking flourished. Picart was illustrating elaborate editions of classical texts and, most pointedly, religious polemics. His positionality as a Huguenot exile is relevant to consider. These "ornaments" participate in discourses around religious conflict and courtly display in the early 18th century. Editor: It is worth pondering how these ornaments might then represent material excess, in the context of early capitalist modes of display and the complicated relationships among class, religion, and representation? Were such embellishments markers of elite status attainable perhaps through exploited labour? Curator: Certainly, these ornamented images speak to tensions that reverberate through that period, in both overt and coded visual forms. Picart challenges the rigid boundaries of the secular and the divine. Notice, for instance, the cherubic figures juxtaposed with stylized vegetation—elements drawn from both religious iconography and natural forms, mediated via Baroque sensibilities. These designs challenge norms around identity, in part, due to that cross-cultural symbolism, but perhaps more sharply because of his self-aware stance as an exiled maker in the Hague. Editor: Right. The method is almost industrial. Consider the transfer of imagery onto copper plate. Then, each pull of the press, resulting in multiplied iterations available for wider circulation. This expands our concept of Baroque aesthetics! And if we see such imagery spread across Europe, we have to consider both the means of making these reproducible forms and who controlled access to these forms as physical property. Curator: That tension is vital. Viewing this engraving is not just about appreciating craftsmanship; it requires reflecting upon historical forces. How was the production and consumption of decorative arts imbricated in broader historical transformations that changed social and political life? Editor: And where do these specific forms arise from? Tracking the social life of motifs like shells or cherubs, what stories are coded within that visual language as it gets replicated for various audiences and means? Curator: Precisely! Approaching it from your angle opens a conversation about production that reveals networks of labor that we can see traces of still now, not least through these patterns that were deployed to make Picart's world and have long survived him. Editor: A crucial lens indeed. Shifting my perspective lets me see it less as ornament and more like a key element in the visual vocabulary of a complex world, which we gain understanding of through deconstructing the process of making it and its varied influences and outcomes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.