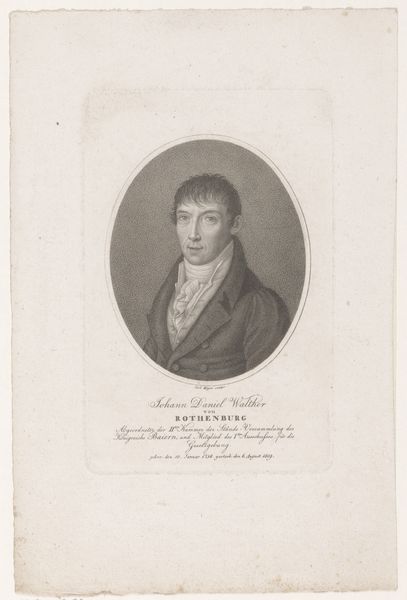

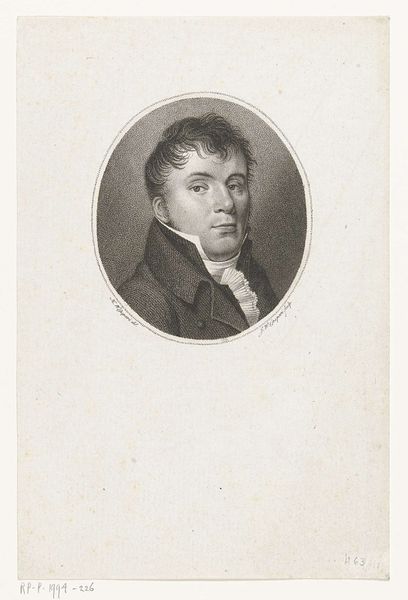

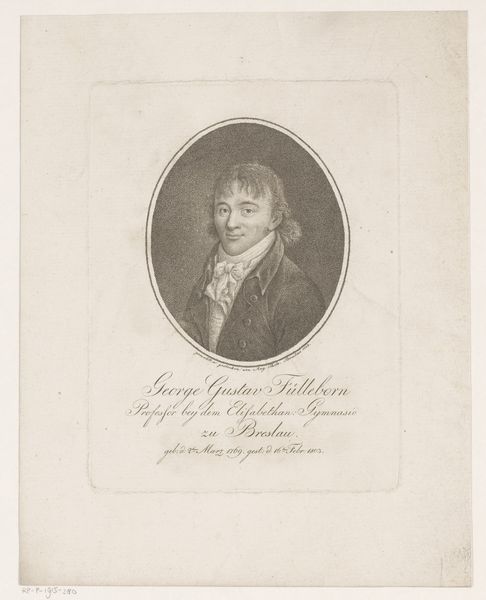

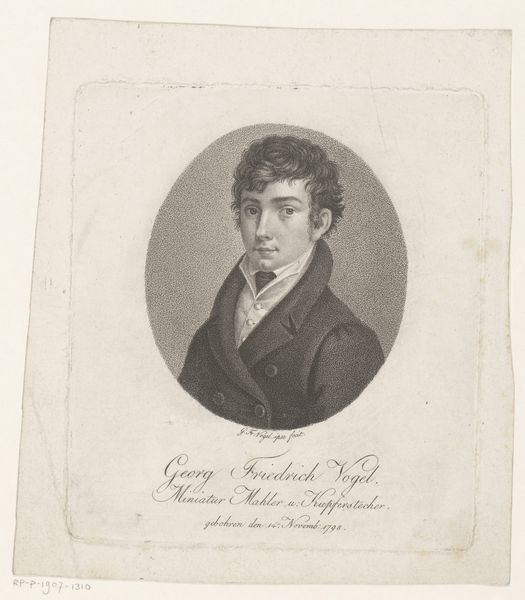

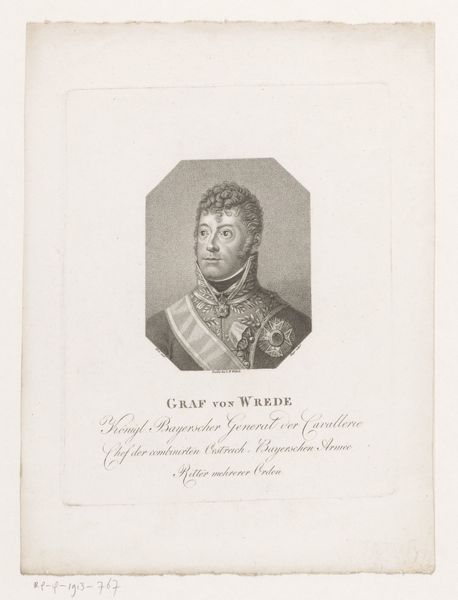

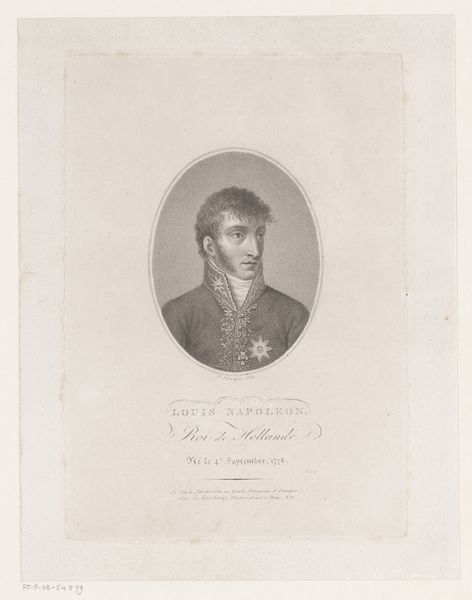

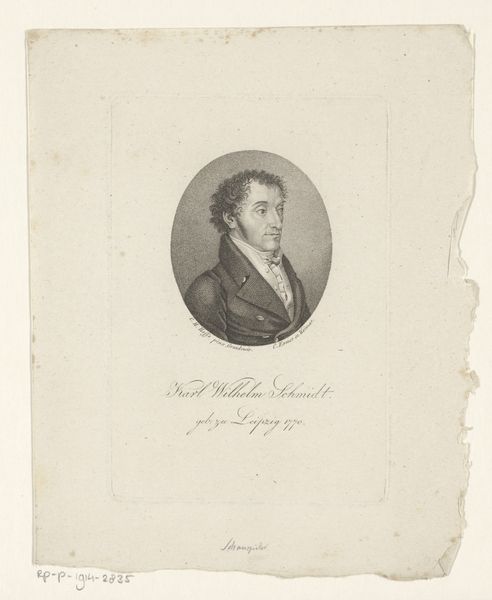

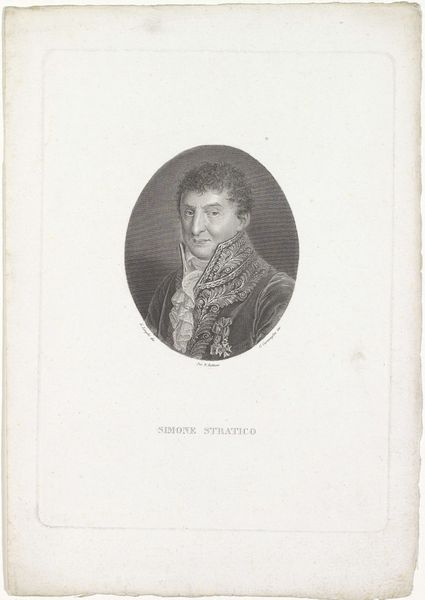

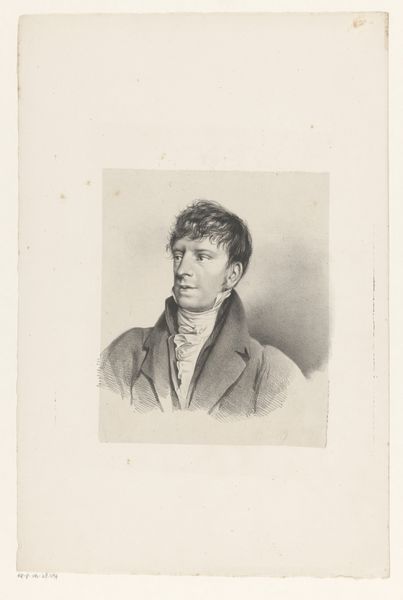

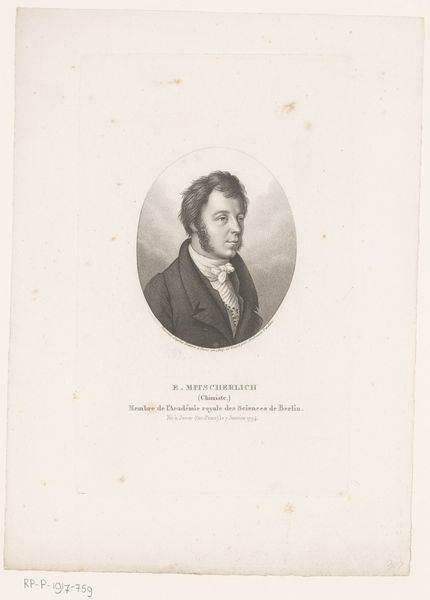

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

romanticism

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, I immediately get a sense of the limitations and constraints placed on self-representation in the early 19th century. The artist, Friedrich Rossmässler, has captured a certain...stoicism, wouldn't you say? Editor: It feels more sentimental to me. A softness conveyed through the fine engraving work – look at the layered lines creating those soft curls, the delicate ruffles. The production values certainly elevated the status of the subject. Curator: Indeed. What we see here is a portrait of George Willem van Schaumburg-Lippe, completed in 1828. What interests me is how this particular depiction upholds the sitter’s elite status through very specific visual cues of the period. It’s more than just a likeness. Editor: Oh, certainly. Consider the context: engravings were, at the time, a primary method for disseminating images. The printmaking process itself, the labor involved in transferring Rossmässler's drawing to the plate, speaks to a demand for images of this nature among a particular social class. Curator: Exactly. We see him positioned within an oval frame, adorned in aristocratic attire. This isn't just about capturing a physical resemblance; it's a carefully constructed statement about power, class, and the societal expectations placed upon him. There's the implicit understanding of dynastic privilege, which he, as a male heir, inherited. Editor: The lines also strike me. Look closely, and you will see tiny inscriptions near the subject’s right shoulder. You can follow how it was produced and consumed. But going back to your first point, do you think its representational strategy allows any flexibility to convey any personal depth, or perhaps vulnerability? Curator: That’s debatable, isn’t it? One could argue that even within the strict conventions of portraiture, an artist can still subtly hint at inner qualities. Rossmässler worked to both uphold the standard representation, yet provide something else... Perhaps a fleeting vulnerability in his eyes? Editor: Perhaps. Still, it all reinforces a message about social hierarchy and status. What intrigues me is what the raw materials of the printing matrix would communicate about such class stratification – were they readily available or scarce and expensive? Curator: Well, reflecting on this piece, it prompts considerations about representation. How much has really changed regarding the power dynamics inherent in portraiture when depicting those with societal advantages? Editor: From my perspective, it’s fascinating how a relatively modest print can illuminate such broader economic and social landscapes of its time. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.