drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 299 mm, width 423 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

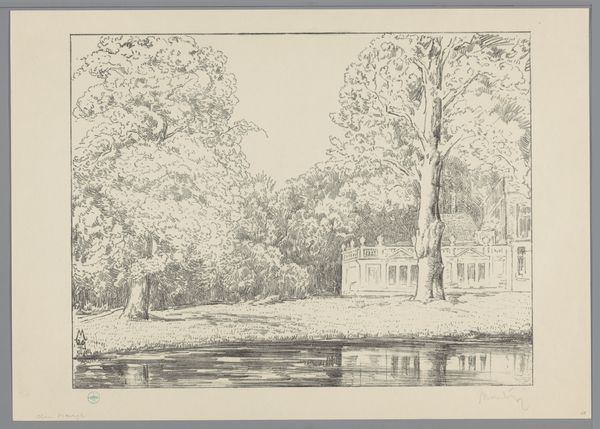

Curator: It looks so peaceful. A very idyllic, almost dreamlike, image of a country house nestled amongst trees. Editor: This is "Gezicht op het landhuis van landgoed Ockenburgh," or "View of the Country House on the Ockenburgh Estate" by Simon Moulijn, created in 1925. It’s a drawing, rendered in ink on paper, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: Ink gives it this amazing depth of texture. I find myself looking closely to recognize those short little strokes, that seem to suggest detail without fully rendering it. The house itself seems almost suspended, framed by the foliage, and this vast expanse of the estate. I find myself wondering what kind of life was once lived here. Editor: Well, Ockenburgh was indeed a grand estate, reflective of a certain social order and a certain style of elite life during the early 20th century in the Netherlands. Places like this represented status, power, and, of course, wealth. Moulijn captures that, but he also emphasizes the visual tropes associated with such buildings – the promise of a peaceful refuge removed from city life. Curator: That makes me think about the symbolism of these estates. They often represented a connection to the land, but also a carefully constructed distance from the realities of rural labor and its attendant social structures. Editor: Exactly. And Moulijn is operating within established visual conventions, a tradition of depicting such places to highlight order, harmony, and cultivated nature, obscuring all signs of labor and social stratification inherent in the history of country estates. Even his choice of ink as a medium evokes precision and permanence that he could use to convey such ideas to his target audience. Curator: It does seem like everything in this scene has been strategically placed. Trees frame the building just so. That manicured lawn stretches almost unrealistically before us. And what about that open cupola-like belvedere? To me that form serves as more of a statement than functional design choice for the time it was built. A nod to enlightenment ideals, even? Editor: Good point. That feature, particularly when accentuated by the rest of the imagery, makes the building appear self-assured, elevated. Think about what kind of narrative the museum supports through such representation of architectural design; what kind of conversations should happen when encountering pieces that seem so simple at first? Curator: Right, the emotional experience can be so much deeper when we unpack those layers of context. Thank you for walking me through the complex layers of this piece! Editor: My pleasure! I hope this conversation helped open some new avenues for understanding art’s public role.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.