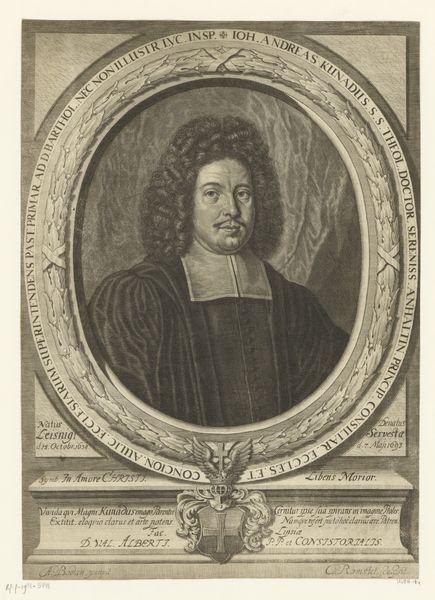

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 340 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Herman Hendrik Quiter's 1679 print, "Portret van Aloysius Bevilacqua." It's an engraving on paper. Editor: It’s somber. Very detailed rendering of the face, but there’s a density, a uniformity of tone that feels almost suffocating. Curator: The engraving technique itself contributes to that, I think. We are seeing a detailed example of period-specific production. Quiter meticulously etched the image, line by line, into a metal plate. It shows how artistic skill translated to printing as a form of production. This artwork highlights the transition from craftsmanship to something that allowed broader distribution. Editor: And dissemination of power. This isn’t just an image; it’s an artifact reflecting social hierarchies. The sitter, Aloysius Bevilacqua, held a significant position within the church hierarchy as evidenced by the text below the image, claiming he held a high position within the Vatican in the area now known as Nijmegen. Portraits like these played a vital role in reinforcing those institutional structures, especially in the baroque era when imagery was used strategically. Curator: Exactly. Consider the materiality further—the choice of paper, the ink used. Were these materials locally sourced, or did they represent wider trade networks? The value judgments of the high art world tend to overshadow the importance of the production behind reproducible media like engravings, making the labor, source and networks less visible. Editor: It certainly prompts us to consider art's public role at the time. Was this image primarily intended for the eyes of other high-ranking church members, as a mark of respect and mutual recognition? Or were they accessible to the broader public as a reminder of power? The copies produced from the engraving extended Bevilacqua’s influence beyond the original audience for an individual portrait. Curator: This deepens our understanding. The work reveals production techniques and social implications. The print enables the church and those in it, to permeate through many levels of 17th century society. Editor: It offers a fascinating glimpse into how an image can act as a tool of social cohesion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.