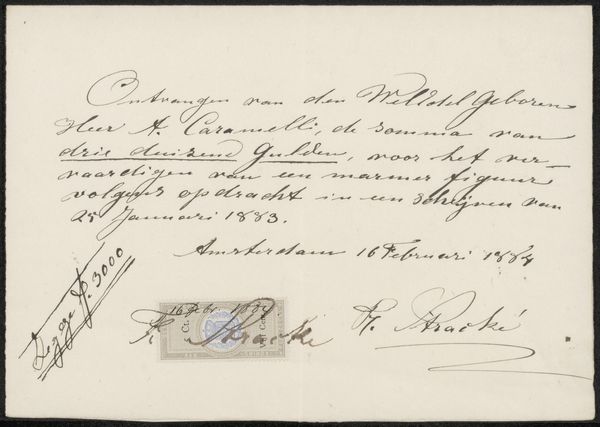

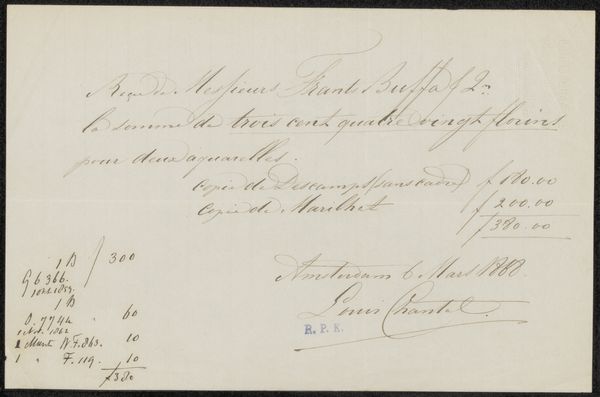

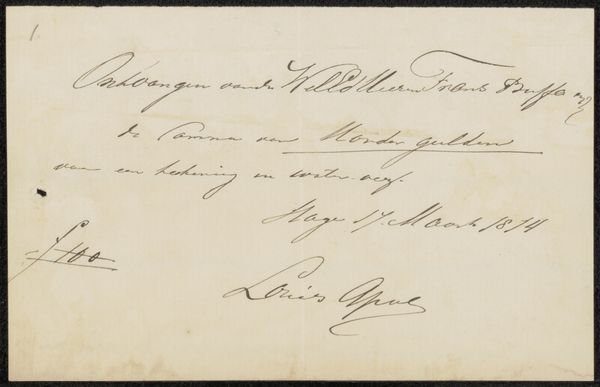

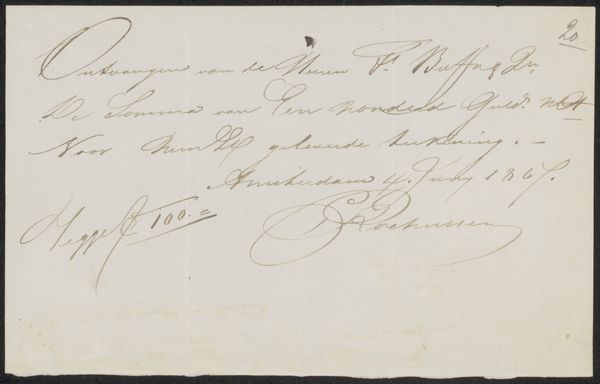

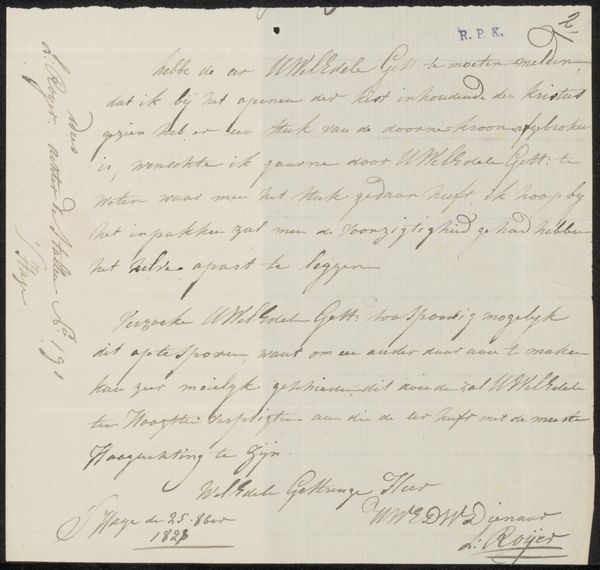

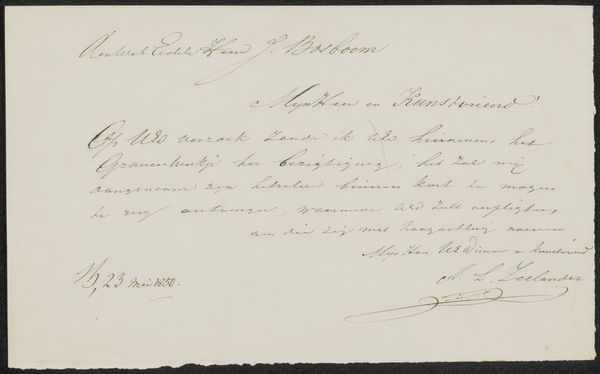

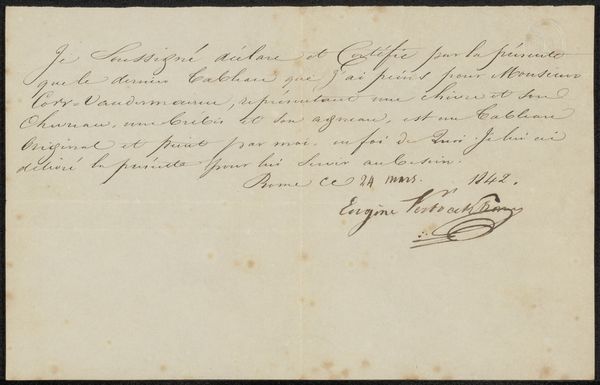

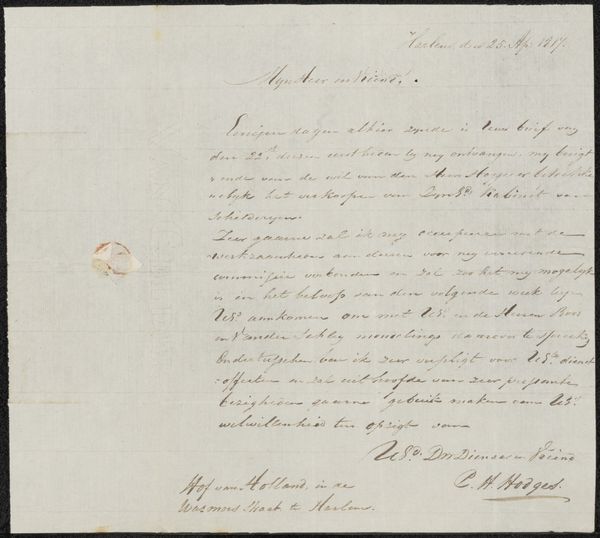

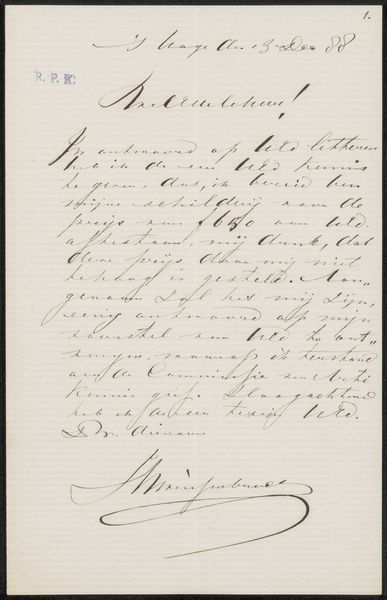

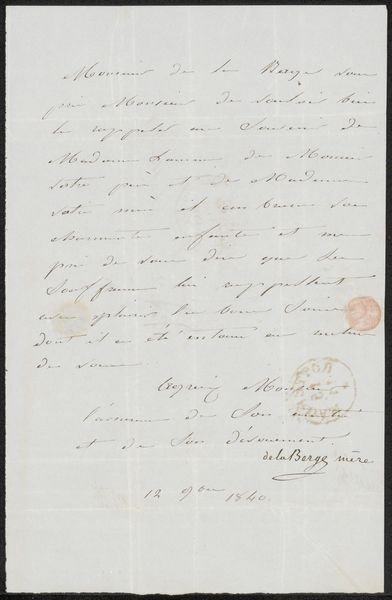

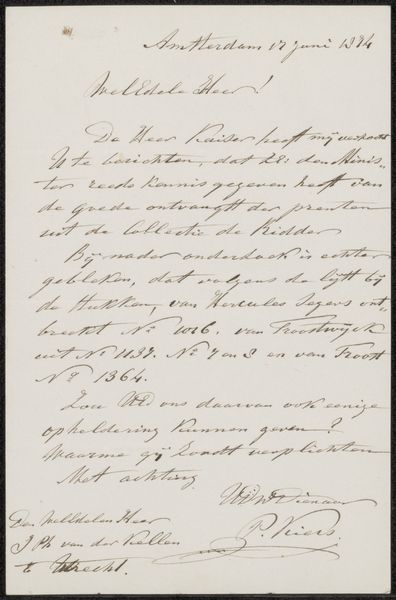

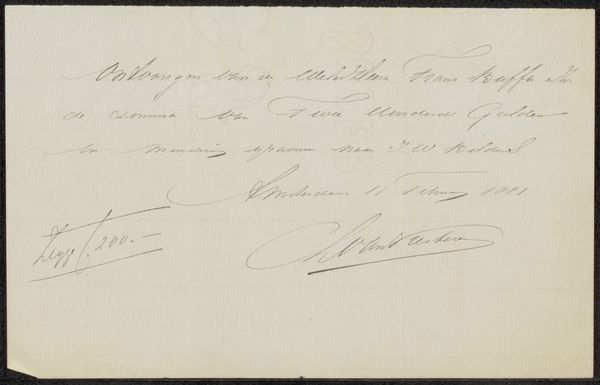

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

script typography

#

hand-lettering

#

dutch-golden-age

#

ink paper printed

#

hand drawn type

#

hand lettering

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

sketchbook art

#

calligraphy

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

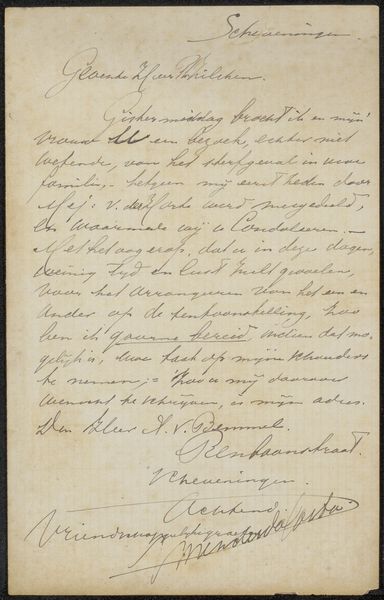

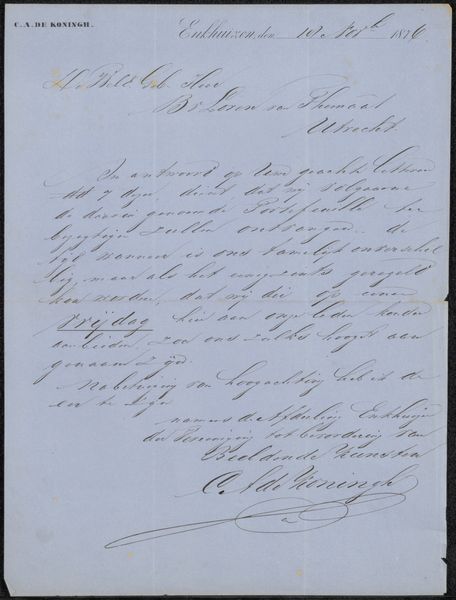

Curator: Here we have "Brief aan August Allebé," thought to be from 1894, by Evert Slaghek. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It feels so fragile and intimate. Look at that delicate ink on paper, like holding a whispered secret. What were the societal expectations on penmanship, and what stories could we infer from that, that are invisible now? Curator: Absolutely. Slaghek's labor in crafting this letter speaks volumes. Think of the precise hand movements required for such elegant penmanship, especially considering it's likely done with a quill. Editor: You can really sense a time of specific craft and labour expectations. Were you required to be neat and beautiful in your lettering to even have work back then? Curator: Exactly! It highlights class distinctions and educational access. Someone with the resources to master calligraphy held a different social position. The paper itself, its quality, even the ink—all point to socioeconomic factors. The letter form, as you were noting earlier, whispers social hierarchy, but in a world before rapid mechanized communication. It really asks you to question what types of art still communicate this clearly now. Editor: Right. We can explore how literacy rates, or lack thereof, further cement societal power structures during the late 19th century in the Netherlands. So the skill of handwriting really solidifies communication? Curator: It was more than that. Calligraphy conveyed intention, social grace, and personal expression, while mirroring those structures of power. It's fascinating how something as seemingly simple as a letter becomes such a rich artifact of its time. The act of reading it even changes through time. Editor: Seeing the material aspects – the paper, the ink, the precise craftsmanship – reminds me that we’re viewing not just a message, but the remnants of complex social forces at work. So something can survive the ages but change in context as our society changes. Curator: I think reflecting on those shifting interpretations, and the continued influence of social structure on what we deem "art" and "craft", enriches our understanding of "Brief aan August Allebé," and how we read artifacts in our society now. Editor: It’s not merely about the text but the whole picture of societal standards back then that help define where the value of something existed. That continues to hold importance for us even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.