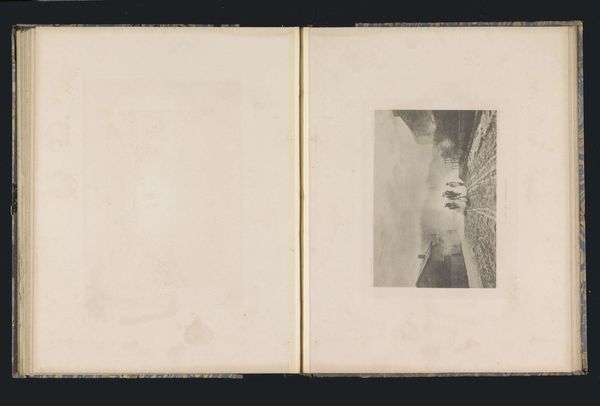

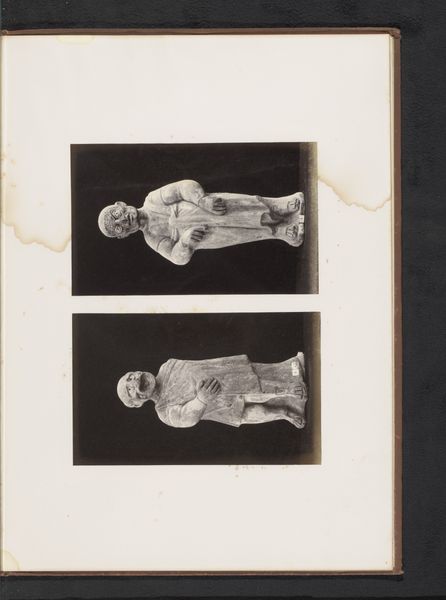

The Labyrinth of Animals; Including Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, & Amphibians - Vol. II 1900 - 1908

0:00

0:00

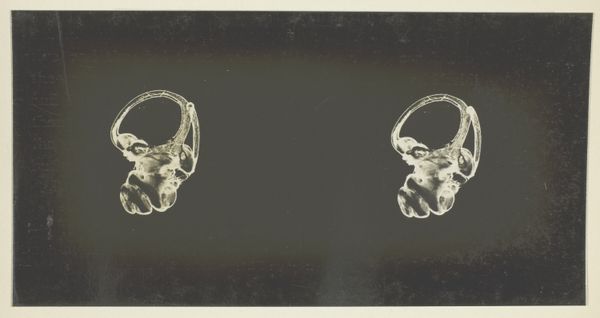

print, paper, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

paper

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Copyright: Public Domain

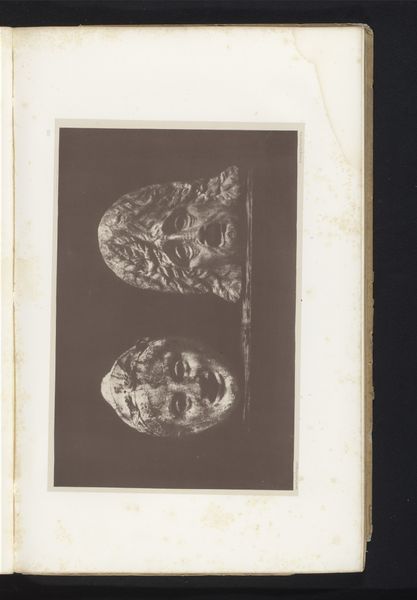

Curator: Here at the Art Institute of Chicago, we're looking at Albert A. Gray’s gelatin silver print, part of "The Labyrinth of Animals; Including Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, & Amphibians - Vol. II", dating from the turn of the century, 1900 to 1908. Editor: Well, immediately I see these strange, almost alien-looking forms floating in a sea of black, they look like ghostly echoes. What are these forms? Curator: Gray created these photographic prints as part of a scientific study into the comparative anatomy of animal ear ossicles. These images reflect not only a scientific, evidentiary gaze, but one intertwined with then-nascent artistic applications. Editor: Oh, ear bones! That context really changes my perspective. Before, I was drawn to the abstract shapes, their almost mystical presence against the void. But knowing they are physical objects, anatomical specimens, makes it more about their biological function, their purpose. Does seeing the forms as functional instead of abstract change their perceived worth? Are they precious because of the knowledge they hold? Curator: This work certainly begs questions of valuation, the objectification inherent in scientific study. Who gets to determine the “worth” of a thing? Here, these bones can represent colonial exploitation, where specimen collections objectify animals while also advancing scientific understandings and discourses that perpetuate a type of racial or biological science. Editor: It's haunting how a scientific pursuit can also hold complex moral implications. These tiny bones whisper narratives far bigger than their physical forms. But this kind of work makes us more sensitive to recognizing how coloniality frames and values a body’s parts. Curator: Precisely. This juxtaposition between scientific study, colonial histories, and their representation, demands that we think critically about the social structures through which our scientific understanding develops. Editor: It makes you wonder, what hidden narratives might be unlocked in seemingly objective renderings. Curator: Indeed, and it reminds us to approach visual documents, especially those claiming scientific neutrality, with an inquisitive, historically-aware perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.