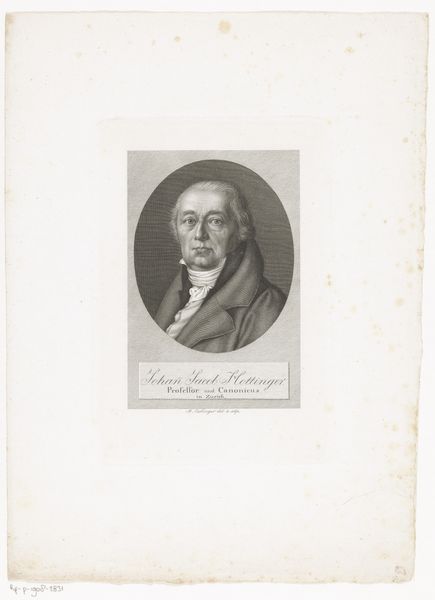

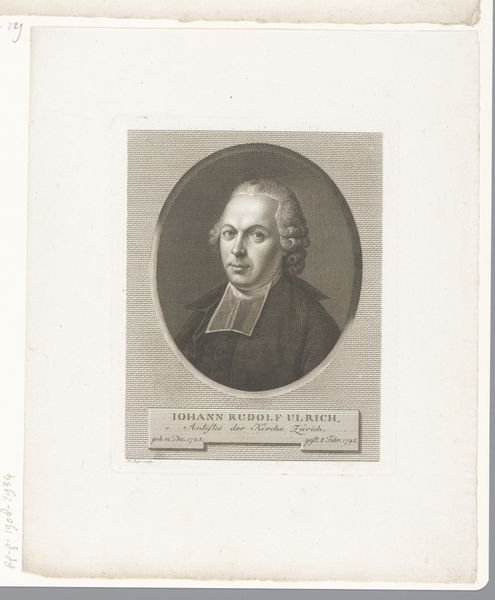

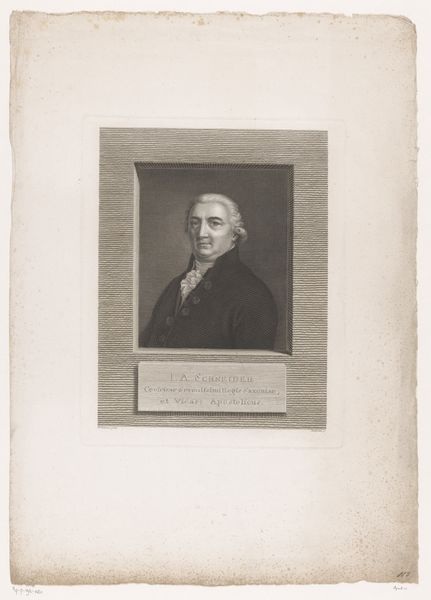

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Johann Heinrich Lips's "Portret van Julius von Soden," dating sometime between 1768 and 1817. It's an engraving, and it's quite striking in its detail despite being seemingly simple. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Well, let's think about what an engraving *is*. It's a print, infinitely reproducible – potentially. Lips is not only portraying Julius von Soden, but he's participating in a process of social representation. This is not a unique painted portrait accessible only to a wealthy patron, but a mechanically produced image available more widely. Think of the socio-economic implications. Editor: So the *act* of creating a print makes the image more democratic and accessible? Curator: Exactly! It’s crucial to remember that producing an image at this time was laborious, and engravings required skill and time. While not quite mass production, it hints at that possibility. Also consider the Neoclassical style - clear lines and austere presentation. Editor: That almost classical feel feels a little stiff, and formal. Is that intentional do you think? Curator: Consider the *material* contrast between that stylistic choice and the means of production. Does the attempt at austere grandeur heighten or diminish the impact, knowing its reproducible nature? Was it truly trying to capture an ideal, or more interested in flattering its subject for social advancement. What's it telling us? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t considered the tension between the style and the process of engraving like that. It really shifts how I see it. Curator: Seeing art through the lens of material production offers powerful insights. We are not looking at a unique image by the artisan hand but a social and economic construction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.