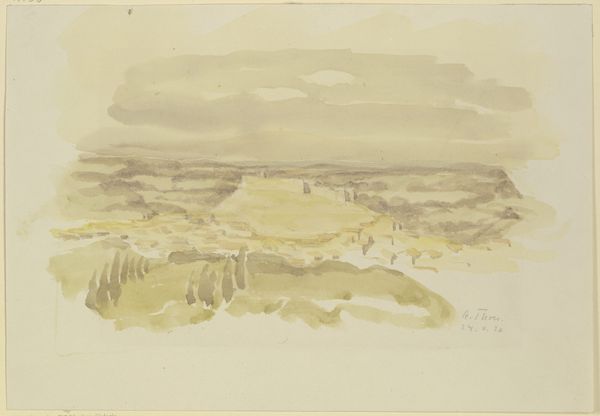

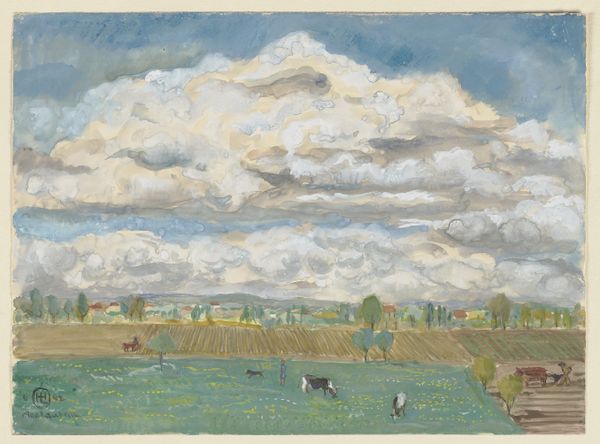

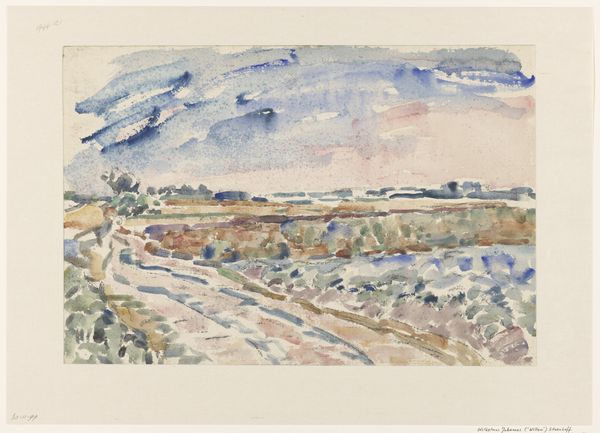

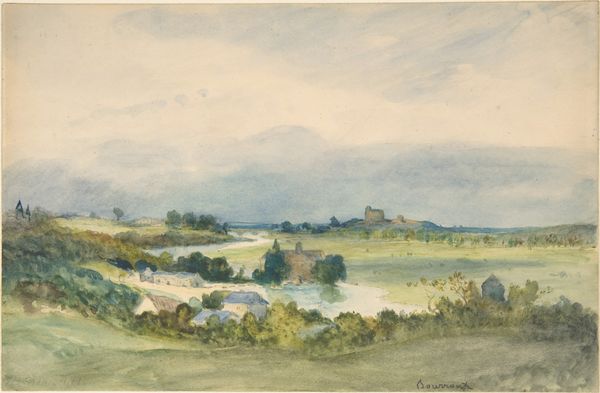

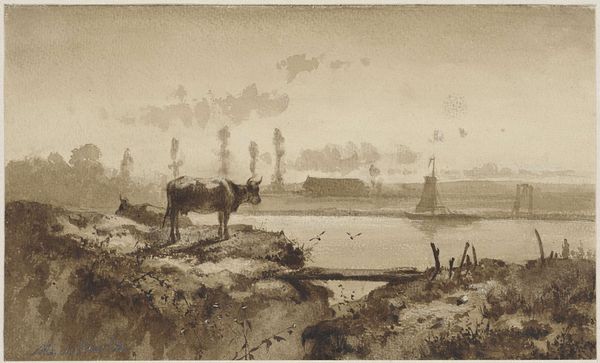

plein-air, watercolor

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

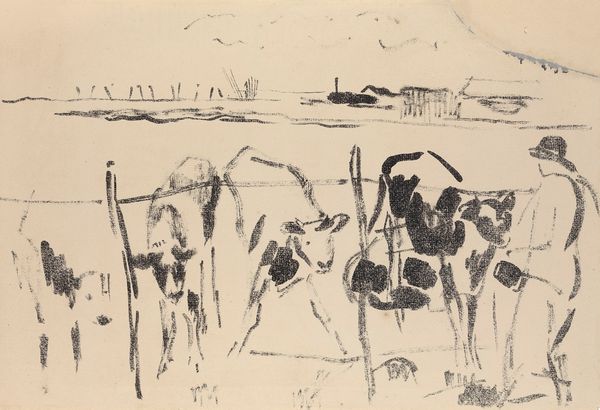

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before an evocative landscape work by Jacob Maris, most likely created between 1847 and 1899. This watercolor, residing at the Rijksmuseum, is known as *Krantenlezer met hoge hoed*, though its literal meaning translates to 'Newspaper Reader with Top Hat'. Editor: That's interesting because I see a tranquil pastoral scene bathed in soft light with cattle. The colors are muted, dominated by greys and greens; there's something so peaceful and atmospheric about it. Almost hazy, like looking back in time through soft focus. It belies its subject…a reader. Curator: Indeed, that haze you detect speaks volumes! Maris was a key figure in the Hague School, deeply influenced by Impressionism. The muted tones and broad, washy strokes here exemplify the *plein-air* tradition. Yet his true mastery lies in capturing the atmospheric qualities of the Dutch landscape. But yes, that subject–reader— that makes the pastoral somewhat deceitful. Editor: It does change things, knowing. Though I see his world. One could ruminate on how Maris perceived his materials: The subtle interaction between watercolor and paper is critical here, and you see this sense of the atmospheric captured with such restraint. But if the focus is meant to be on the man reading? Curator: Perhaps that's misdirection. Maris frequently employed seemingly commonplace subjects – windmills, boats, and of course, cows— as conduits to explore deeper emotional and even psychological states. The figure might be less about news and more about a mood or a space. Consider what the imagery conveys of Holland at this time… a quickly industrializing nation finding ways to hold onto something more primal in its collective memory. Editor: Yes, industrial versus primal-- I'd wondered. That smokestack in the distance – does it also feature that sense of impending transformation of work through industry? How these pastoral lands also function as places of consumption, places of production? It’s that stark material presence that defines our experience, reminding us of shifting landscape that isn't natural, so to speak. Curator: An incredibly important note. So maybe the reader isn't simply taking in information but wrestling with the symbolic weight of his world's past as contrasted by an unsure industrial future… a transition of old to new. Editor: Precisely. Viewing Maris’ landscape through the lens of labor, through its medium, we discover this tension between art and the making of living. It does create tension and complexity beyond the traditional bounds of romantic landscape, wouldn't you agree? Curator: Absolutely! Thinking about all of this I come away with an expanded understanding of Jacob Maris—the Hague School— and the layered symbolism interwoven throughout seemingly serene Dutch scenes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.