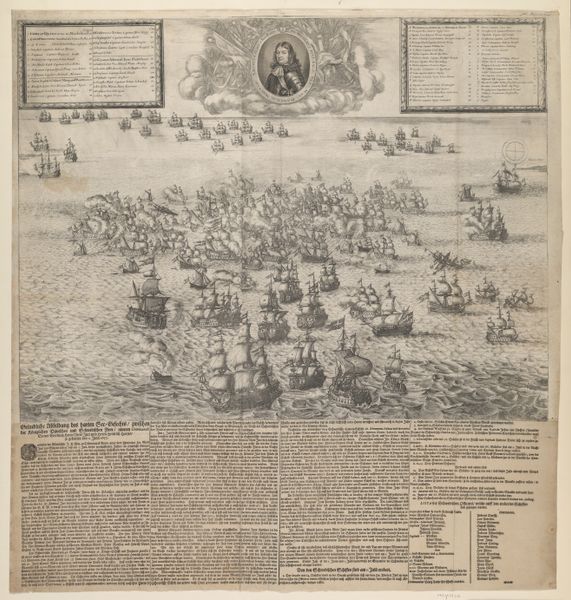

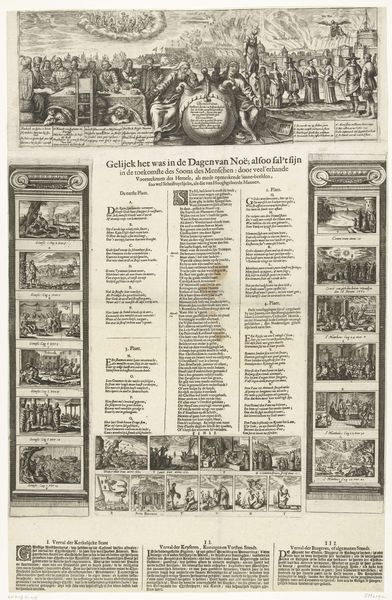

Dimensions: height 525 mm, width 418 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

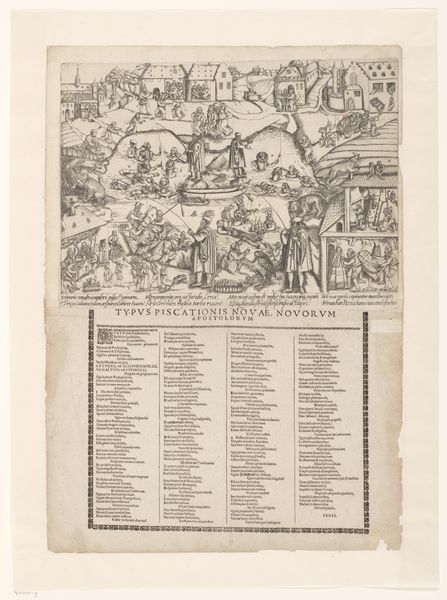

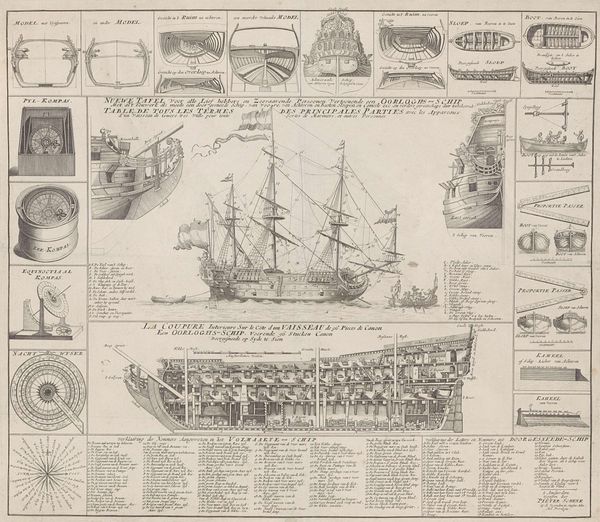

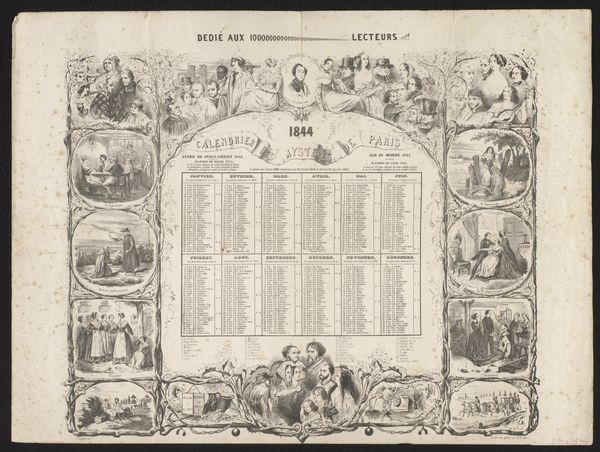

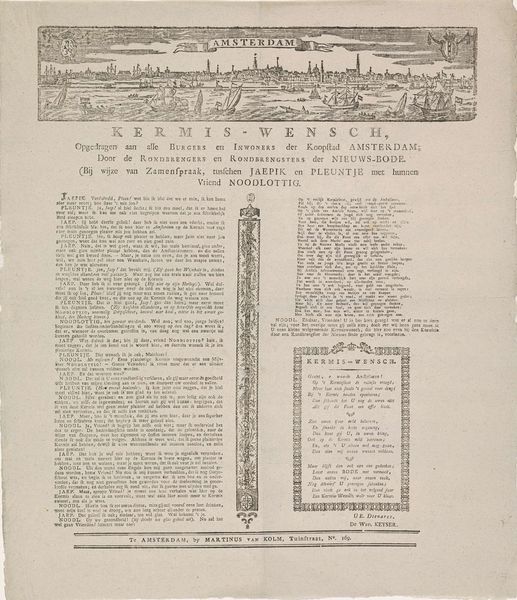

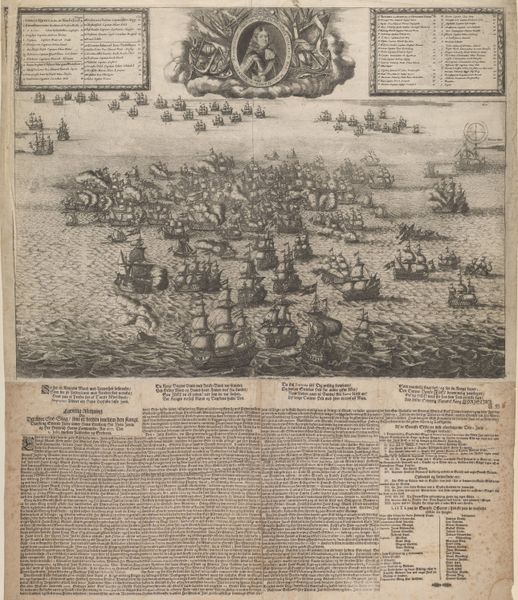

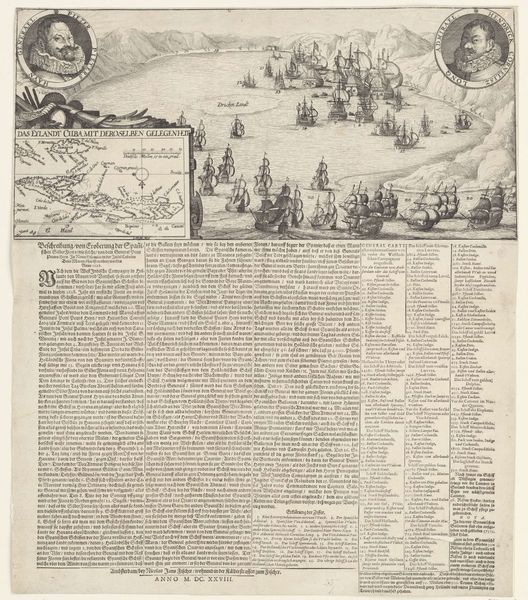

Curator: At first glance, I see an intricate landscape with what seems like calendar dates and information panels superimposed beneath a lively naval battle scene. There's a stark tension between celebration and rote function, or perhaps those two functions worked hand in hand. What do you think? Editor: Well, initially, I am struck by the process used to create this curious amalgamation, titled “Almanak met de verovering van de Zilvervloot door Piet Hein in 1628". Given that this print using the etching medium dates from 1787-1788, there’s an obvious mass production aspect—likely to promote this heroic battle scene for popular consumption through almanacs for 'Comptoir en Huis’ -- office and home. It’s fascinating that such a widely reproducible method was employed. Curator: Indeed, notice the image up top: this commemorates the Dutch capture of the Spanish treasure fleet in 1628. These sea battles of imposing ships hold so much weight symbolically: pride, authority, power! Consider how visually similar iconography was and still is adopted across time to celebrate power and valor, no matter the cultural specifics. It carries collective meaning to each person, no matter the background. Editor: Right, but how accessible would such prints actually be? Who possessed the capital to both obtain and display these, and how does its reception transform from being situated in a merchant's office, as opposed to the household sphere implied on the calendar. Think too of the engraver, hunched over their tools to convey this naval battle. We might appreciate this battle from the comfort of our galleries, but the maker was working within entirely different economies and politics, embedded in various structures of servitude. Curator: A very valid point. But let's also consider the long shadow cast by historical events and how a relatively “recent” war for them has been memorialized in this way through its placement upon the more quotidian device of the almanac. Consider that perhaps its ready access for many families normalizes it and even uses it to promote ideas of mercantile valor. Editor: That said, thinking about its materiality has expanded my understanding, considering both the intent of mass production but with a critical examination of that historical intention of wide viewership in 1787. Curator: Absolutely, examining the symbolism inherent to collective understanding alongside production methods, reveals so much.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.