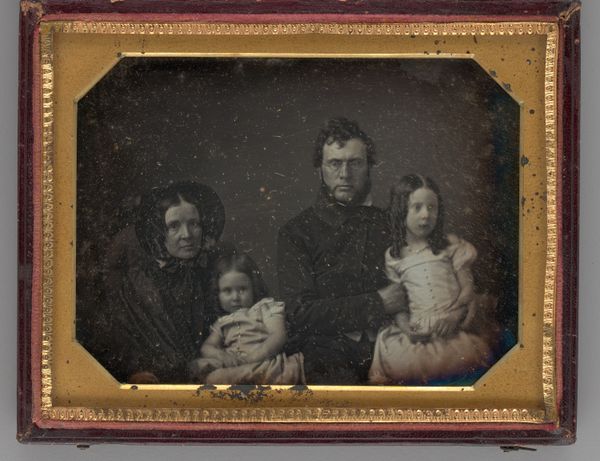

daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

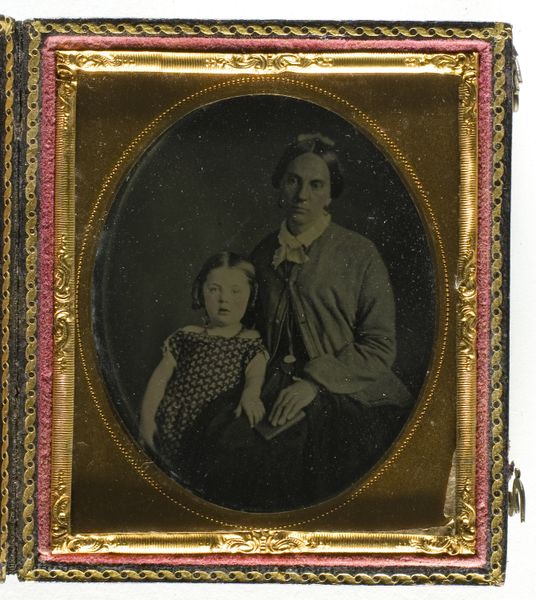

mother

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

oil painting

#

framed image

#

romanticism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 88 mm, height 150 mm, width 117 mm, thickness 15 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this portrait, it’s difficult not to think about the constraints placed on women during this time. This daguerreotype, titled "Portret van een onbekende moeder en kind" – or “Portrait of an Unknown Mother and Child” was taken sometime between 1844 and 1852 by an unidentified artist. Editor: It feels intensely private, almost secretive. The image is quite dark, and the composition with its golden frame focuses our attention on the two figures. They look stiff, though…a bit uneasy. Curator: Right, the photographic process in the mid-19th century was still quite novel, so the subjects likely had to sit still for quite a long time. But consider the socio-political implications: portraits like these democratized representation. Previously, portraits were the domain of the wealthy, reinforcing a class structure through art. Now, more families, even if not affluent, could participate. Editor: That's true. But it also seems to play into a sentimentalized view of motherhood that was taking hold at the time. I wonder about the societal pressure this unknown mother felt to project this image of maternal bliss. Were women like her allowed more visibility, yes, but in roles strictly defined by their relationship to husband and child? Curator: An interesting point! This reflects broader debates on domesticity, gender roles, and female education of that era. Perhaps she's holding onto that child just a bit tighter to affirm her primary, publicly accepted role. Also, think about the power dynamics involved – the professional photographer, likely a man, shaping the narrative, freezing this representation of idealized maternity in time. Editor: Absolutely. I look at it, and I see a powerful yet muted statement, both capturing a moment of personal significance and perpetuating the expected visual vocabulary of the time. A reminder that even supposedly objective media like photography always exists within complex webs of social and political forces. Curator: It brings new light on the power of imagery and what it means to create art within systems of power. Editor: A potent thought indeed that makes us evaluate all portraitures of the period with a critical lens.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.