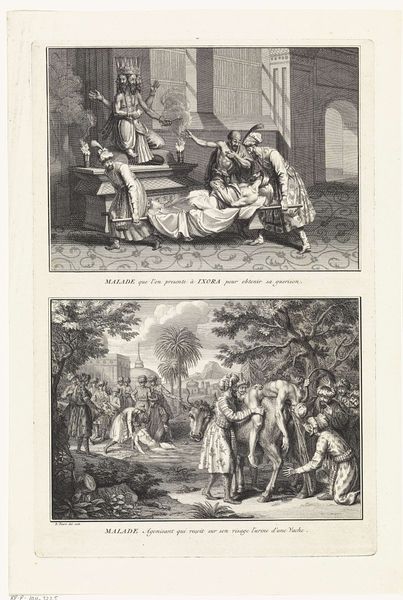

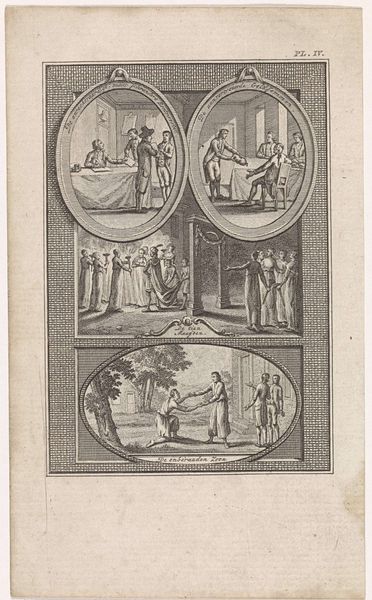

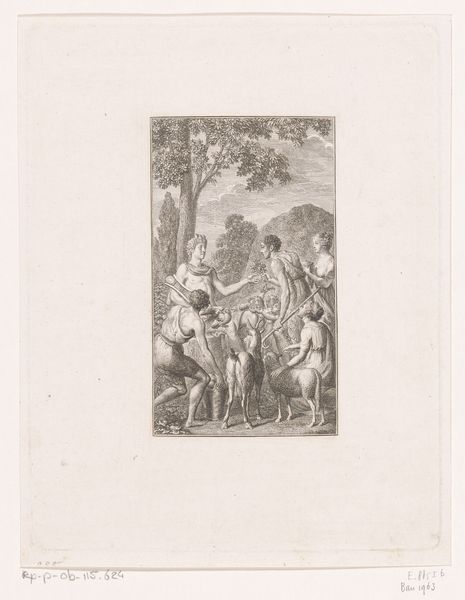

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 297 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving created between 1724 and 1726 by Jan Lamsvelt, entitled "De prinsessen Noer El Tadjoe en Begquem Saheb," which currently resides in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It strikes me as a very formal depiction, almost theatrical. The composition is split into two distinct scenes, each seemingly self-contained within its framed space. There's a curious stillness despite the implied narrative. Curator: Indeed, the two-part presentation mimics diptychs and polyptychs common in devotional images—however, here, it's repurposed to juxtapose contrasting scenes of leisure. Observe how symbols function here; a servant offers a headdress in the upper scene, while another tends a reclining woman with a fan below. Both images are designed with the clear intention of emphasizing status and wealth. Editor: Formally speaking, I’m fascinated by the lines. The sharp, clean lines delineate every detail, giving the image an almost hyper-real clarity. Notice how Lamsvelt uses cross-hatching to create subtle tonal variations, almost mimicking the effects of chiaroscuro in painting. The varying densities create volume and texture. Curator: And if we dig into that symbolism, these images highlight aspects of power. One scene involves preparation, signifying control, while the other, the languid relaxation. They aren't just portraits but visualizations of the women’s roles. I am drawn to how they negotiate a fine line between public appearance and private vulnerability. Editor: Do you think the stark contrast in the depictions could relate to Baroque aesthetics influencing its representation, a fascination with opposing elements and implied theatricality? The precise architectural rendering adds a sense of constructed artifice, fitting that period’s interest in control and reason, but also suggesting underlying artifice in representing real lives. Curator: Perhaps, but within Islamic Art—in the more narrative genre aspects of that framework—it functions to instruct. It visually reinforces their rank, while telling a story for the viewer—a type of accessible narrative meant for widespread circulation through prints. This is no candid shot, but constructed visibility. Editor: Right, and in its totality, this particular engraving speaks to an elaborate and intricate performance between reality and artistic convention. It leaves me thinking how deeply cultural constructs shape perception itself. Curator: Yes, precisely; an elegant window, meticulously framed, offering layers upon layers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.