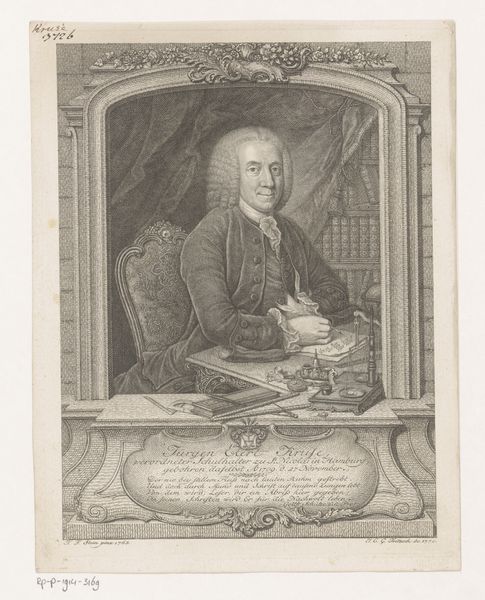

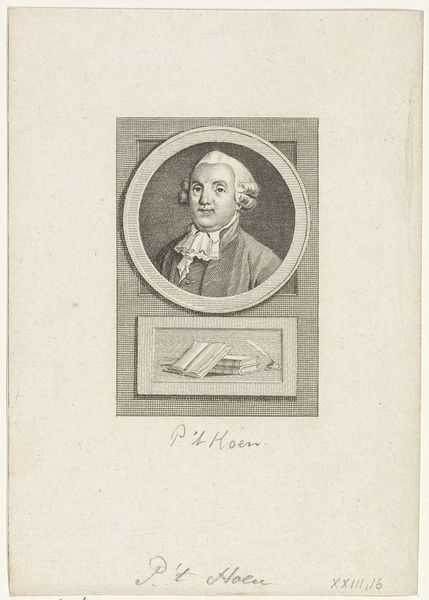

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 314 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a printed portrait of Hendrik Karel Nicolaas van der Noot, dating from between 1789 and 1793, made by Theodorus de Roode. It's a fine example of late 18th-century portraiture. Editor: My initial impression is of restraint and formality. The limited palette and careful etching suggest a need for decorum, but then the eyes looking off to the left provide just enough motion and personality. Curator: Yes, the neoclassical style is certainly present. The engraving technique allows for remarkable precision in rendering the sitter's likeness and the details of his clothing and surroundings, note also the use of oval composition that frames the subject. Editor: But beyond the aesthetic choices, consider the labor. Each line, each bit of shading, required someone skilled in the precise art of engraving. And what was the societal value ascribed to that labor? Was de Roode's hand elevated or simply instrumental in service of depicting van der Noot? Curator: An interesting point. Although the Neoclassical style seems focused on idealized forms, within that stylistic paradigm, close inspection shows a detailed realism and compositional balance between Van der Noot, writing materials, and stage curtains. The textures, skillfully captured, also indicate much about the historical context of the time. Editor: Exactly. And speaking of context, the choice of engraving itself speaks volumes about accessibility. This wasn't a unique oil painting intended for a wealthy patron, but a reproducible image. Consider its function and dissemination in solidifying Van der Noot's image, particularly when we account for the historical period where he actively sought allies in the revolt against Emperor Joseph II. Curator: Indeed, and the engraver's labor becomes even more complex. De Roode does not simply copy, but he must skillfully interpret painting and form a translation into linear work. De Roode’s aesthetic decisions become fused to our perception of Van der Noot’s character, immortalized with sharp edges and defined tonalities. Editor: Right, a political project dependent upon the engraver’s capacity and understanding. One begins to wonder, did he support Van der Noot’s position? Or, perhaps more practically, how much was he paid, and what influence might that financial incentive exert over the final result? Curator: An insightful way to approach the piece. By examining the artistic execution with its historical moment and medium, the artistic choices by Theodorus de Roode and subsequent questions regarding both subject and artmaking further enrich and offer nuanced readings. Editor: Absolutely, the image’s material origins and wider dissemination become crucial layers when assessing it not merely as a portrait but as a historical object itself, bound to production conditions of labor and ideological investment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.