photography, architecture

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

photography

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 357 mm, width 267 mm, height 480 mm, width 321 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

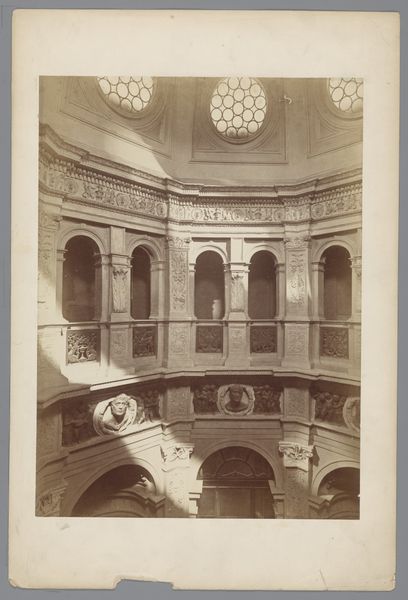

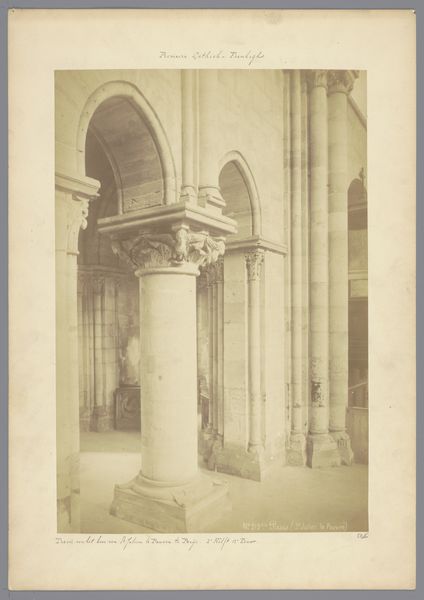

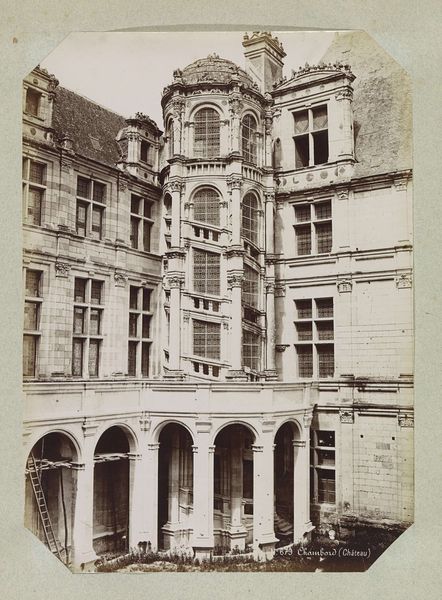

Curator: We're looking at an albumen print attributed to Pompeo Pozzi, titled "View of a Courtyard, probably in Italy," dating from around 1851 to 1880. What's your initial impression? Editor: My immediate reaction is one of confinement. There’s a stark geometry to it, all sharp angles and regulated rhythm of those classical columns. It feels rather weighty. Curator: Yes, the weight of the stone is palpable. Notice how Pozzi meticulously captures the architectural detail: the fluted columns, the decorative friezes, even the precise time displayed on that prominent clock face. It presents a formal, almost rigid composition. Editor: Precisely. It makes me think about the labor involved in extracting, transporting, and carving all this stone. And the implied social hierarchy that demanded this level of embellishment. This photograph is evidence of massive resource expenditure. Who was the client and what did he stand to gain from this opulent display? Curator: That’s a keen observation. In purely formal terms, though, consider how Pozzi uses light and shadow to accentuate the three-dimensional quality of the architecture. The light isn’t soft, exactly, but there’s an effort here to create an interesting interplay between dark and light. Editor: And yet that specific, calculated manipulation has everything to do with the production and social history of this type of image. The architecture in question—Roman revival style no doubt—needed to have visual ‘presence’ to convince patrons. Hence, light becomes yet another material used by workers to construct social spectacle, for commerce. Curator: Perhaps. Still, focusing on the forms, that tension creates depth and brings a stark beauty to the otherwise impersonal space. Editor: For me it speaks of power and control – of labor forced towards someone’s end. I now wonder how many prints like this the photographer produced at the time? These considerations also need attention, instead of being exclusively dedicated to matters of aesthetic merit and pictorialist intent, even if, like here, these may come to feel mutually connected and impossible to completely divorce from one another. Curator: An important final remark. By engaging both perspectives we’ve seen not only the visual components, but something of the historical machinery that underlies what might appear to be a static photograph.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.