print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

realism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

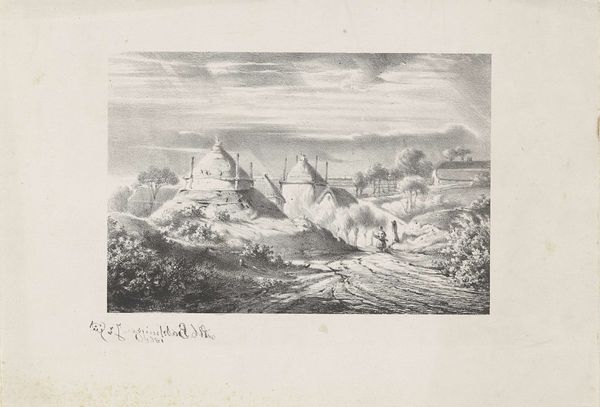

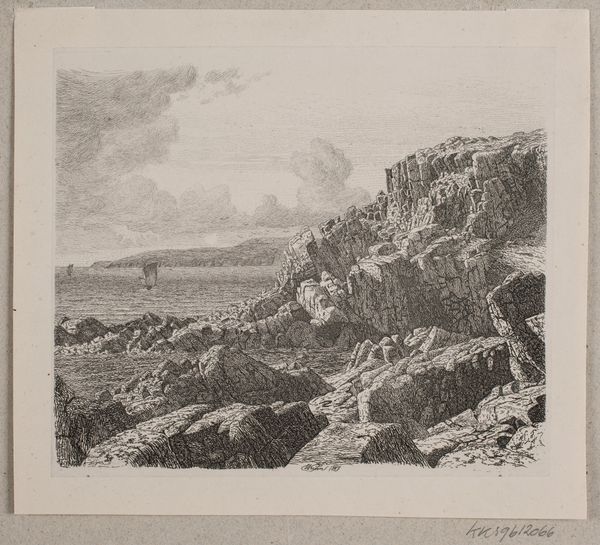

Curator: Before us is Joseph Pennell’s 1910 etching, "Work Castles, Wilkesbarre". Editor: My initial impression is one of muted grandeur. The etching's grayscale and vast sky evoke a feeling of industrial ambition juxtaposed against a serene, almost desolate landscape. Curator: Pennell was fascinated by industry, wasn't he? We see that manifested here. This work sits within a larger tradition of depicting industry as a kind of heroic endeavor. However, when contextualized, the depiction of Wilkes-Barre specifically touches upon significant narratives about the social and labor conditions within Pennsylvania’s coal mining regions at the time. Editor: Exactly, the materiality of this etching is revealing. Consider the copper plate, the acid used to etch the design, and the press that transferred it onto paper. These material processes reflect the industrial era it represents. Furthermore, think of the laborers involved in creating and distributing these images—they are implicitly part of this industrial landscape. Curator: It makes me think about the tradition of landscape painting that often romanticized rural settings, usually sidelining human industry altogether. What are we to make of Pennell’s approach to blurring boundaries between labor and leisure in this sooty depiction of nature? Editor: Absolutely. It’s a shift, though an uneven one. Even in depicting labor, the work retains a sense of aesthetic detachment. What about the consumption of this image? Did the working class see representations like this and feel acknowledged or exploited further? Who were the consumers and patrons? Curator: And who decides which materials and which landscapes merit artistic depiction and preservation? There is the inherent bias of seeing through the lens of a single male artist. I’m reminded of recent discussions around ecofeminism and how such landscapes and laborers were invariably and unequally gendered, raced, and economically oppressed. Editor: I agree; understanding those material networks of production, distribution, and consumption, as well as labor relations in these spaces are key. It's not enough just to interpret it as "landscape". Curator: Understanding these layered histories brings new insight, especially by connecting the narratives of exploitation, landscape, and material conditions of printmaking. It pushes us beyond merely aesthetic appreciation and confronts difficult histories that art, and specifically landscape art, has frequently tried to smooth over. Editor: Precisely, engaging with this work has prompted a needed reminder of the social and material underpinnings that shape both the making and viewing of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.