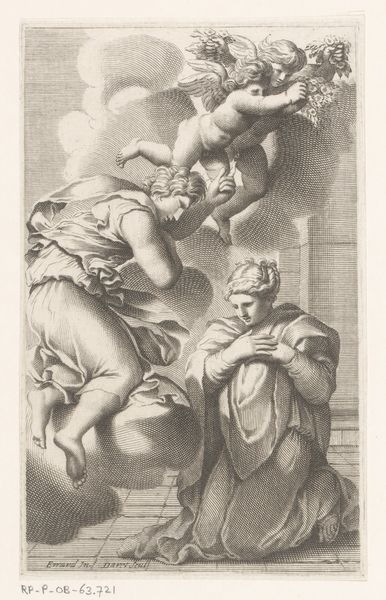

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 13 1/4 × 7 9/16 in. (33.6 × 19.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look at the dynamism in this print! Michel Dorigny created "Saint Margaret" in 1639. The engraving depicts Saint Margaret's triumph over a dragon. Editor: Immediately, I am struck by this contrast of delicacy and violence. Her robe billows as she emerges triumphant. It feels so Baroque, the drama dialed all the way up. It feels a little...exploitative, focusing on the spectacle of her conquering this beast, what do you think? Curator: It certainly adheres to that aesthetic! And the visual vocabulary—angels swooping in, bestowing laurels... it’s classical, yes, but then infused with Counter-Reformation zeal. Notice how the saint's gaze and gesture direct us upward toward salvation and redemption in the face of the dragon’s implied evil? Editor: Absolutely. The positioning reinforces the patriarchal power dynamic that she represents. Is she saving herself, or simply acting as an allegorical figurehead representing some other social, political, religious struggle, through which men consolidate their power? What do you think that dragon represents? Perhaps that period's view of female sexuality and autonomy: a dangerous, chaotic force that must be conquered, maybe even stomped down upon? Curator: Well, dragons in Christian iconography often symbolized paganism or heresy. In that period it could easily represent chaos itself, quelled by faith. Margaret, then, would symbolize the unwavering belief. Also, note the column fragment behind her – classical ruins always carry a connotation of a lost, perhaps decadent, past now superseded by the Christian present. She is literally atop those ruins, isn't she? Editor: True. Her foot is firmly planted on the defeated beast. I still question if the image merely uses her legend as a vehicle to send that broader message, you know? Regardless of the story, an image of female power and dominance gets packaged with religious, and arguably patriarchal, justification. I wonder how the print was received in its time, though. Who was its intended audience, and what did they see? Curator: Those are excellent points. Perhaps for viewers in 17th century France, its function would have been devotional as much as anything, reminding them of the rewards for withstanding temptation and upholding the faith. But even devotional objects reflect underlying social assumptions and agendas. Editor: I appreciate how analyzing such works forces us to confront those difficult nuances of power and faith. It is also so very stylishly composed! Curator: A vital message delivered with extraordinary baroque verve indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.