drawing, watercolor, sculpture

#

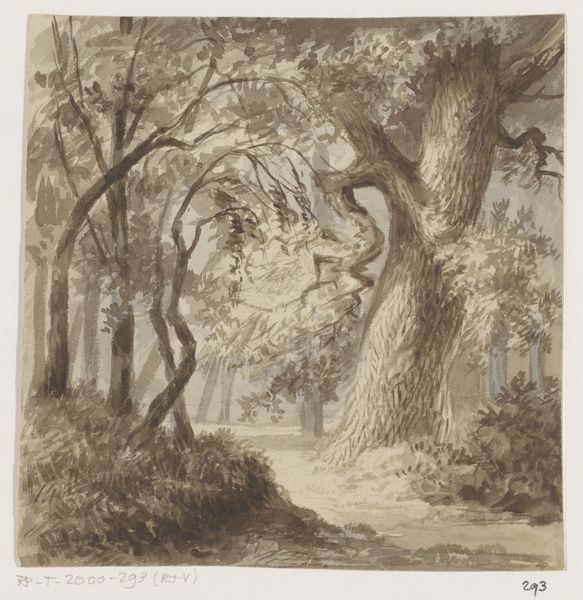

drawing

#

statue

#

pencil sketch

#

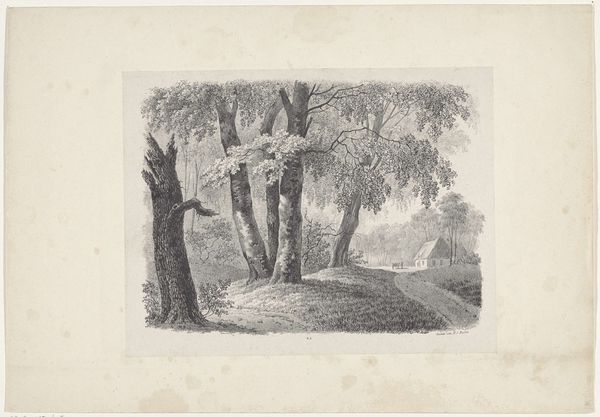

landscape

#

watercolor

#

sculpture

#

romanticism

#

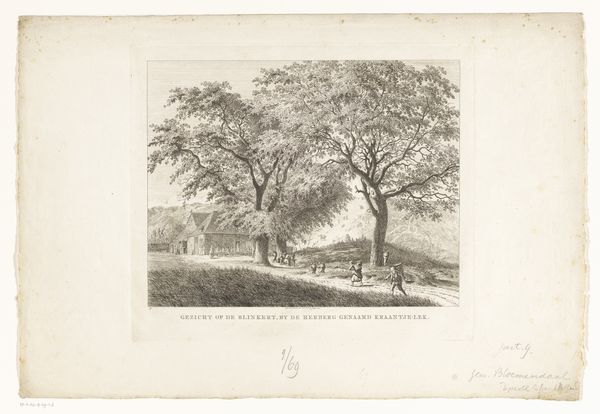

park

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 312 mm, width 384 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I am immediately transported. This is a drawing titled "Tuinbeelden in Chiswick Park," placing us in that idyllic spot sometime between 1800 and 1864, courtesy of William Henry Hunt. Look at how the artist uses watercolor to capture this beautiful scene. Editor: It does have a dreamy quality, doesn't it? I'm struck by the balance and the subtle interplay between nature and these man-made statues. It's like a stage set. Are we meant to see this park as a sanctuary? Who had access to such spaces? Curator: That's a thought-provoking question. The statues are classical in style. I'm thinking about how landscapes became symbols of power, ownership, and the carefully constructed ideals of beauty favored by the upper classes. Editor: Right, these types of parks weren't public in the way we understand it today. It raises questions about privilege, doesn't it? Land ownership was closely linked to wealth and social status. Curator: Absolutely. Now, thinking just of the artistic element... Hunt uses light to lead your eye into the composition, doesn't he? The soft, diffused light makes it seem timeless and melancholic, almost dreamlike. Editor: And I see that as both a technical skill and a kind of romantic longing. How do we reckon with romanticising landscapes when their accessibility was historically restricted and steeped in inequality? Is this art perpetuating or questioning this dynamic? Curator: Hmmm. It's an interesting dilemma, and one I think Hunt invites us to contemplate by juxtaposing nature and classical art. In truth, though, maybe the truth lies somewhere in between those two narratives. The personal appreciation for natural beauty and the acknowledgment of the social context in which that beauty exists. Editor: Agreed. There's a lot more than what first meets the eye here. It definitely offers some nice reflection points.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.