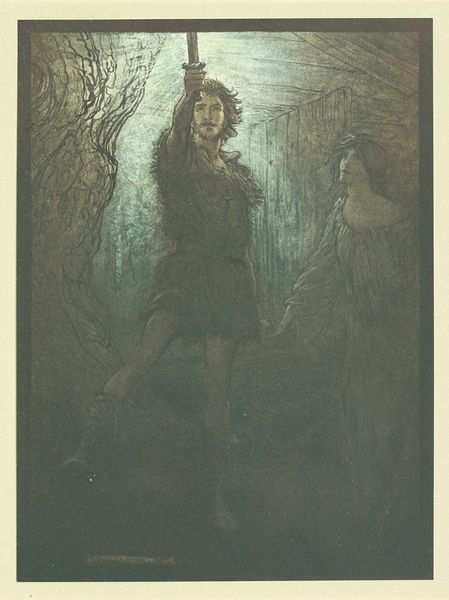

Picture of Taira no Tadamori Capturing the Priest of Midō Temple c. 1884

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 13 5/8 × 28 1/8 in. (34.61 × 71.44 cm) (sight, vertical ōban triptych)

Copyright: Public Domain

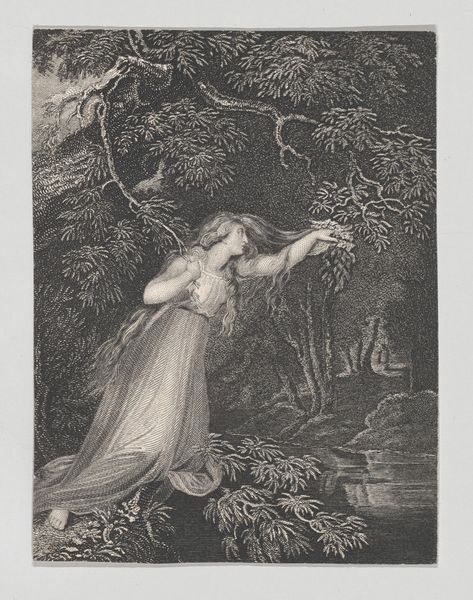

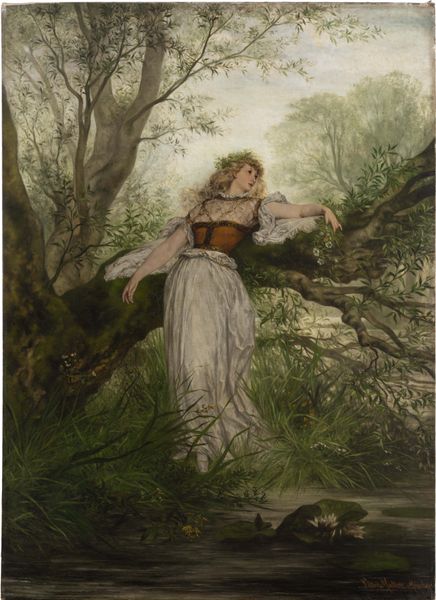

Curator: My immediate sense is…unsettling. This scene evokes a world where the ordinary is breached by the uncanny. A kind of Japanese gothic, maybe? Editor: Indeed. What we have here is Kobayashi Kiyochika’s circa 1884 print, "Picture of Taira no Tadamori Capturing the Priest of Midō Temple," housed here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Crafted using ink and watercolor on paper. Notice the ukiyo-e tradition, a clear marker of its origins. It's fascinating how printmaking enables the democratization of art, bringing scenes like this to a broader audience than, say, an oil painting would. Curator: Ukiyo-e often captured daily life, the pleasure districts, actors. But this…this is different. Look at the setting: a flooded forest, those stark tree trunks mirroring the equally stark temple lanterns. There's a real drama unfolding. Editor: Let's dig into that drama, shall we? The story behind it implicates class struggle. The legend goes that Tadamori, tasked with temple construction, suspects a priest of illicit behavior, disguises himself, and infiltrates a secret meeting. Curator: A master of disguise and deception! And there’s the priest – or is it? The figure seems less godly and more…deranged, almost feral with disheveled hair and tattered clothes. Is it societal alienation personified? Editor: Note also the specific labor here. The careful carving of the woodblocks to create such depth, such watery reflections! This highlights the incredible skill involved in the printing process—the division of labor that sees the artist create the design, then skilled artisans interpret and transfer it onto the block. It forces us to recognize the collective, the human input behind what seems like a singular artwork. Curator: Right, the process itself becomes part of the story. Kiyochika often infused his prints with a modern sensibility, this interplay of light and shadow, Western perspective blended with traditional Japanese aesthetics. And those watery reflections...they add another layer of ethereal depth, creating unease, suggesting something lurking beneath the surface. Editor: I’d also like to emphasize Kiyochika’s social consciousness—his willingness to break from standard ukiyo-e subject matter. A critical reflection on power, corruption, and social inequalities in Meiji-era Japan is clear here. Curator: Yes, he took a simple ghost story and, with light, composition and dramatic form, and of course the story it illustrates he amplified it with complex layers of commentary on the power of its society. It goes beyond simple decoration or telling of popular folktales. Editor: Indeed, it makes you think about the systems and labor practices in art making but also question what and whose histories we depict and how labor and class interplay in our storytelling. Curator: This print becomes a subtle window into a much larger narrative tapestry woven with tradition, conflict, and hidden truths, unsettling indeed.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The warrior Taira Tadamori (1096–1153) was serving the retired emperor Shirakawa (1053–1129) when, one rainy night, they set out to visit a favorite concubine in the Gion district of Kyoto. On the way, a ghost-like figure appeared among the trees of a shrine. Tadamori went to subdue the beast but discovered that in fact it was an old priest with a small torch and a pot of oil, replenishing the lanterns. The emperor rewarded Tadamori's courage by granting him his concubine.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.