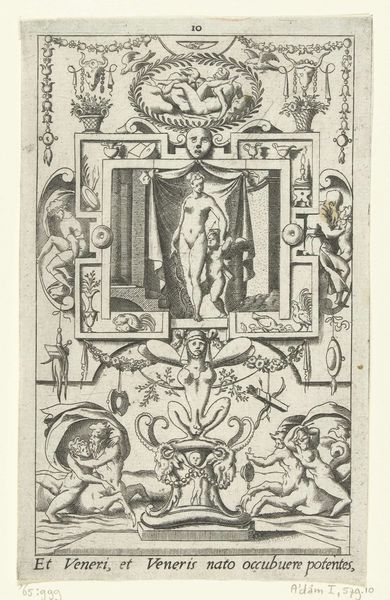

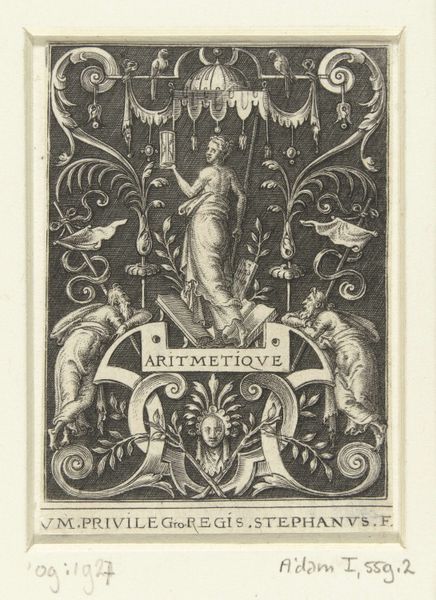

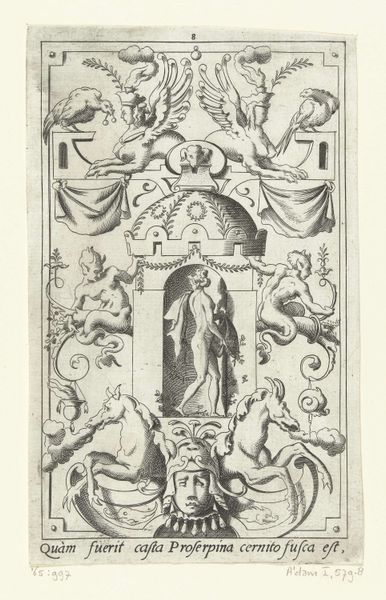

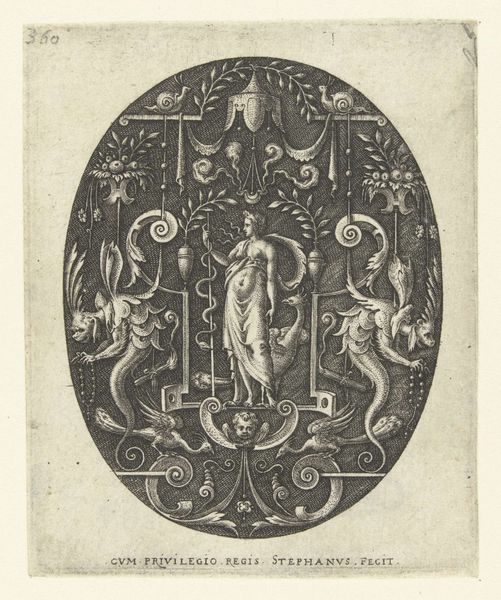

drawing, print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

metal

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 57 mm, width 42 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I get a feeling of ornate preciousness from this work. It's so detailed! I just want to hold it like a charm. Editor: Indeed, that jewel-like quality is part of what makes "Diana with the Moon in her Hand," so compelling. Created by Étienne Delaune sometime between 1528 and 1583, this engraving showcases the artist’s exceptional skill in metalwork and printmaking during the Renaissance. Curator: Diana... goddess of the hunt, right? The moon she's holding really cements that lunar connection. But, wow, look at all the ornamentation—almost feels more decorative than reverential. I mean, the balance in the composition is amazing, too—those fantastical dragon-tailed creatures flanking her… almost makes me think the sacred gets dressed up, put on display like everything else at court. Editor: You're right. This period certainly saw a surge in emblem books and allegorical representations where gods and goddesses were used to symbolize virtues, attributes, or even political ideals. In that vein, think of the print in this case not only as a symbolic image but also as a piece of courtly art. Note also the Mannerist style – elegant, elongated figures and intricate details were definitely fashionable. The image itself, like many, circulated widely. Curator: Interesting to think about it being widely distributed; kind of flattens the notion of originality in art, doesn’t it? Every wealthy family with space in the salon likely could have possessed this icon! Still, something about her expression remains really intriguing to me – a bit aloof and self-assured amidst all that fanfare and imagery, that’s hard to ignore, right? Almost has this quiet defiance in those features. Editor: Definitely. We should acknowledge that artists weren't always entirely free in how they interpreted these figures, even if personal touches found a way in. Delaune probably operated within certain courtly constraints or at the very least, expectations for such work. Still, seeing this tiny print reminds me how adaptable such ideas became at that time. To close on that thought, remember what you feel looking at this – preciousness but balanced with purpose – maybe hints a little about this Renaissance world we tried to explain with such simple-seeming drawings. Curator: Absolutely. It is a conversation with another age, a real invitation. And for me the drawing offers a little reminder that strength often resides not in grand pronouncements, but rather from a thoughtful balance of symbolism and intimate touch.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.