painting

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

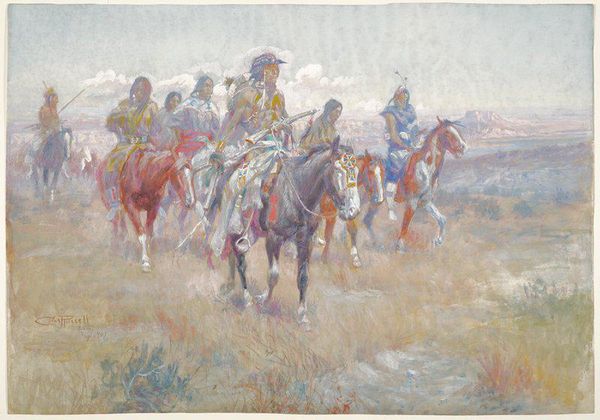

watercolor

Dimensions: 16 5/8 x 27 5/8in. (42.2 x 70.2cm)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

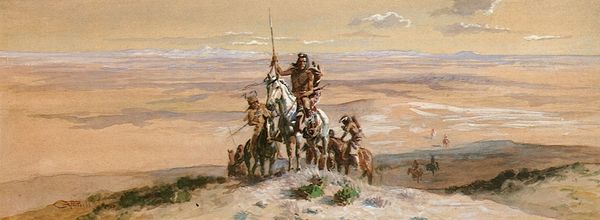

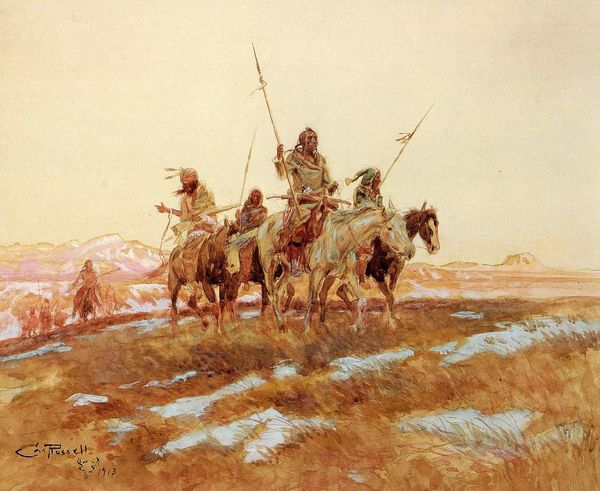

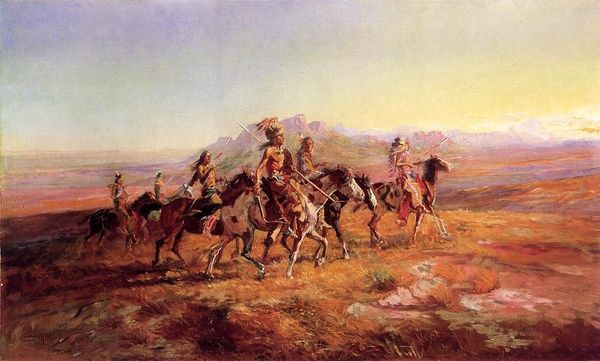

Curator: Looking at Charles M. Russell's 1897 watercolor, "Indians on Horseback," I'm immediately drawn into a vast, dreamlike expanse, where figures seem to emerge from the very dust of the landscape. Editor: Dust is right! It’s palpable, isn’t it? I'm wondering about the pigments Russell used—ochres, primarily? He seems to have ground them himself, imbuing the work with a sense of place through the land’s very materiality. Curator: Perhaps. It’s less about precision and more about a felt presence. Look how he evokes the movement of the horses—not with photographic detail, but with an almost spiritual rhythm, the watercolor itself seeming to gallop across the page. He wasn't just depicting; he was embodying the West. Editor: Embodying and perhaps, in some way, mythologizing. Watercolor as a medium lends itself to the romantic, easily traveling, commercial. We should not look past how the art market, then and now, is key to constructing these images. This work, lovely as it is, participates in the narrative of the 'vanishing' West. Curator: But the humanity, surely, remains palpable! Each figure is individual, bearing his own weight and story. Do you see the glint of light on the spear, the texture of the leather? It speaks to a deep respect for their lifeways, for their relationship to their tools and animals. Editor: Agreed, but the tools and animals are equally material markers, symbols of power relations—the horse representing both freedom and a kind of imposed hierarchy among tribes post-colonization. Think of the sheer labor and resources that go into maintaining those saddles. The 'romance' hides so much. Curator: Perhaps it's about memory then—Russell capturing a fleeting moment, not just of physical presence, but of a culture on the brink. Isn’t there a poignant beauty in that delicate preservation, using something as simple as watercolor? Editor: Simple, yet loaded. The affordability of watercolor made images of the American West widely consumable. Even the choice of medium carries cultural and economic implications within the broader history of representation. Curator: Well, whatever the implications, the image stays with you, doesn’t it? The figures are riding, and you feel a sense of forward movement, into the clouds and into history itself. Editor: Indeed. A movement fueled by the very ground they traverse, a ground that's been labored over, traded upon, and contested—leaving its marks in the art, and in the broader landscape of history.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Charles M. Russell was born in St. Louis, Missouri. Shortly after his 16th birthday, he left for Montana to pursue his lifelong dream of being a cowboy. He worked as a cowboy and wrangler for 11 years and documented his experiences through sketches, paintings, and modeled figures. Russell’s paintings reveal a deep admiration for Native Americans and especially the Plains peoples. His close observation of their traditional dress, weapons, and horses is apparent here in details that indicate these men are members of the Apsáalooke (Crow) tribe. The scene is likely a hunting or scouting party—whether actual or imagined is unknown.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.