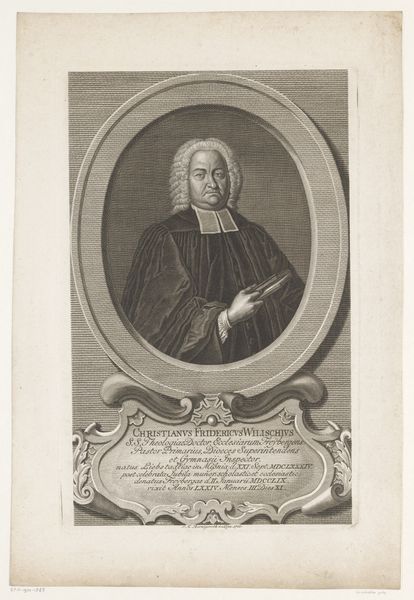

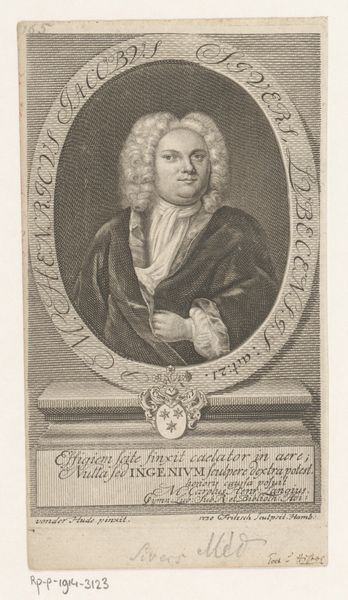

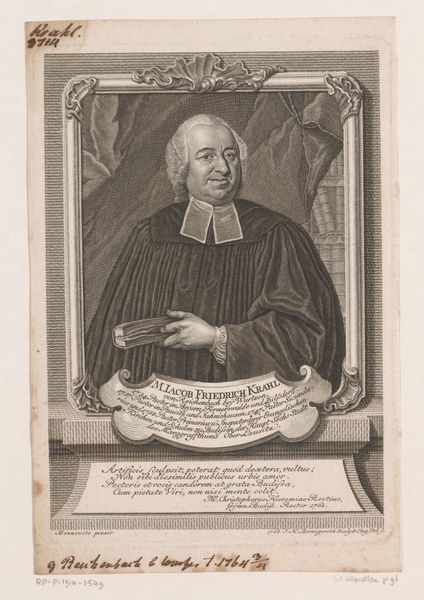

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 114 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

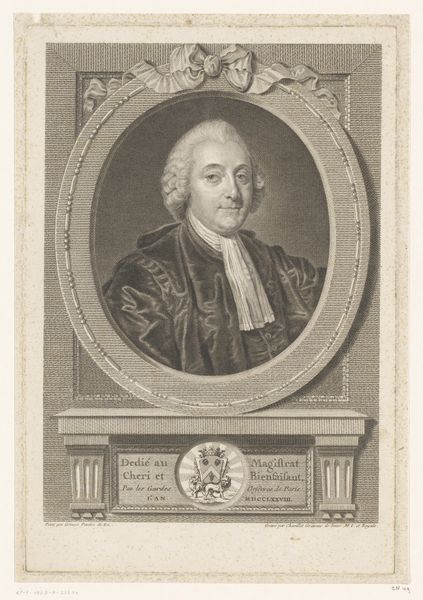

Curator: Let's discuss this intriguing engraving titled "Portret van Gottlob Benjamin Weinmann," created in 1782 by Johann Christian Gottfried Fritzsch. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Hmm, my first thought is: this feels like a carefully constructed performance of power. The wig, the somber attire, the ornate frame – it’s all signaling authority. It gives the feeling that it lacks personality, just repeating codes of class. Curator: Precisely. This portrait participates in a broader visual language. Note how Weinmann, an Evangelical preacher, is presented within this oval frame, complete with a decorative ribbon above. It firmly situates him within the religious and social hierarchy of his time. His clothing speaks volumes; the cut and fabric indicate not only his profession but his status within the church. It reinforces historical assumptions of who could take on the identity of cleric, so Weinmann's status has many layers to unpack. Editor: It’s so…controlled, though, isn't it? Like every line in this engraving is calculated to project respectability. And maybe that's why it’s a little bit funny to me. What secrets or wild passions are lurking beneath that perfect wig? Curator: It's interesting that you consider his presentation in relationship to something suppressed, a lack of expression. We might consider it in relationship to contemporary performances of self through social media, in which identity is mediated through technology. Is Weinmann not presenting a perfectly manicured self? What freedoms are or are not available across history? Editor: Okay, okay, fair point! But still, the severe formality leaves me a little cold. I’m always more drawn to the messy, the human…give me a portrait with a smudge of charcoal or a misplaced brushstroke! Curator: Even those “imperfections,” though, can be read as constructed elements! However, returning to Weinmann, this print would likely have served to disseminate his image and authority throughout his community, and further cement existing ideas around the church as authority. Editor: So, what we see—or don't see—tells us more about the systems at play than about Weinmann, the man himself? Curator: Absolutely. Ultimately, this image becomes a potent symbol of faith, class, and power in 18th-century society. Editor: Right, the absence almost speaks volumes. The spaces in between always reveal the interesting part!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.