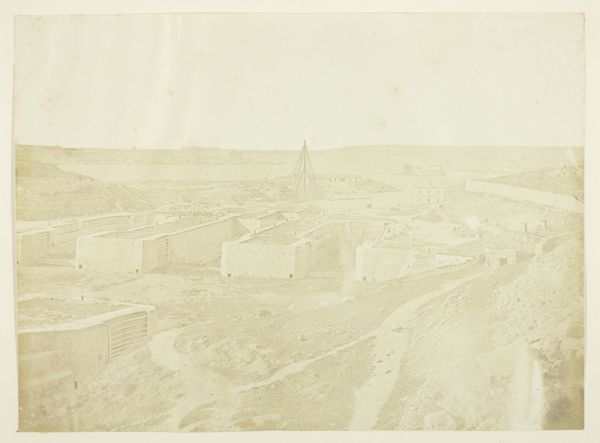

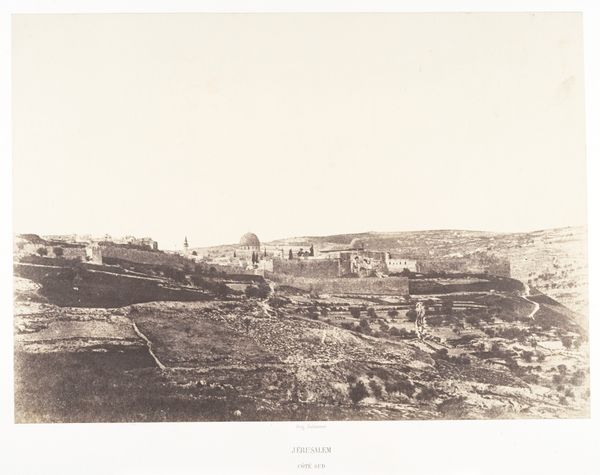

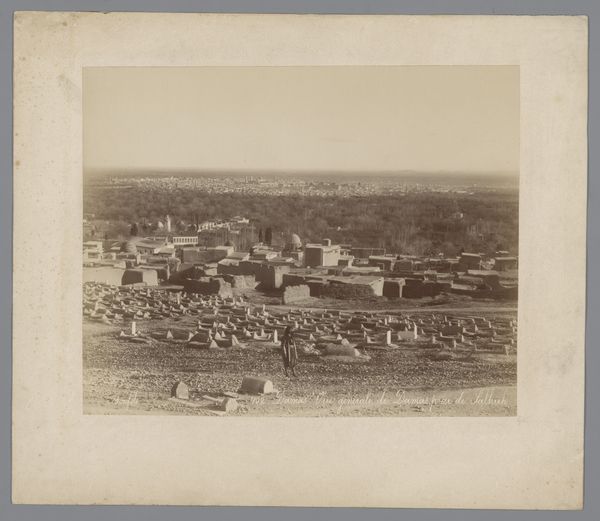

Buildings in Sebastopol, View Taken from the Redan 1855

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

cityscape

Dimensions: 22.2 × 29.8 cm (image/paper); 32 × 40.5 cm (mount/page)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's explore "Buildings in Sebastopol, View Taken from the Redan," a daguerreotype captured by James Robertson in 1855. The work resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: I'm immediately struck by the sheer devastation. There's a ghostly, ethereal quality to the light, almost as if the destruction itself is radiating outward. It seems strangely compelling, like peering into a faded memory of collective trauma. Curator: It's powerful, isn’t it? We're looking at a pivotal moment frozen in time, at the aftermath of the Crimean War. This wasn't just a military campaign; it was a moment that challenged notions of empire and exposed social and technological transformations in Europe. Robertson's image, rather intentionally I'd say, becomes a site of memory and reflection. Editor: Absolutely. I find myself thinking about the physical process, how the daguerreotype itself, this metal plate treated with chemicals, captures light reflected off rubble and ruin. The labor of war, of building and destroying, is etched materially onto the plate. And how that original process connects to the labor of Robertson in that moment to create such work during wartime conditions is compelling too. Curator: Exactly, think of who had access to photography then and who was likely kept away from these images, a kind of intentional witnessing if you will. The Redan, a heavily fortified British position, provides Robertson with a vantage point, which immediately implies a perspective. That compositional choice speaks volumes. It hints at imperial power, but it also unveils the consequences of conflict on a city and its inhabitants. Who benefited? And at whose expense? Editor: You bring up a key point—benefit. While Robertson may have sought to document or even sensationalize, the stark imagery also exposes the immense human cost of geopolitical strategies. The very means of producing this image--photography--becomes intertwined with empire and war. Curator: This single image serves as both a historical record and a stark reminder of war’s impact on both tangible environments and intangible societal structures. It forces us to reflect on what "progress" really entails and who bears the brunt of its advancement. Editor: Agreed. It encourages a necessary and ongoing engagement with uncomfortable truths embedded in the legacies of conflict, materiality and technological process.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.