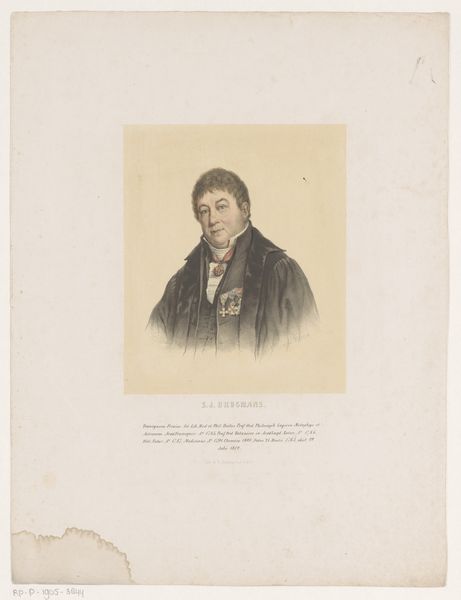

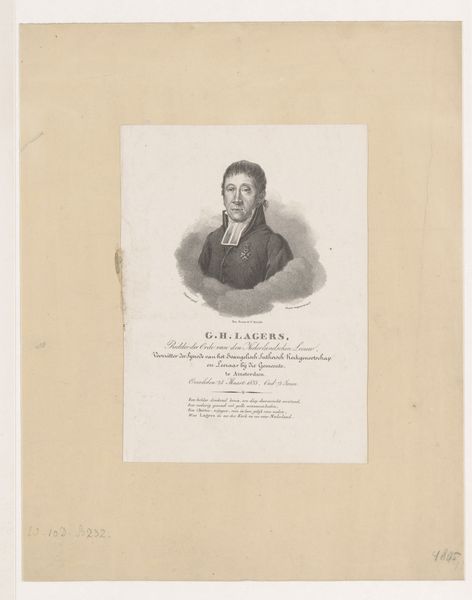

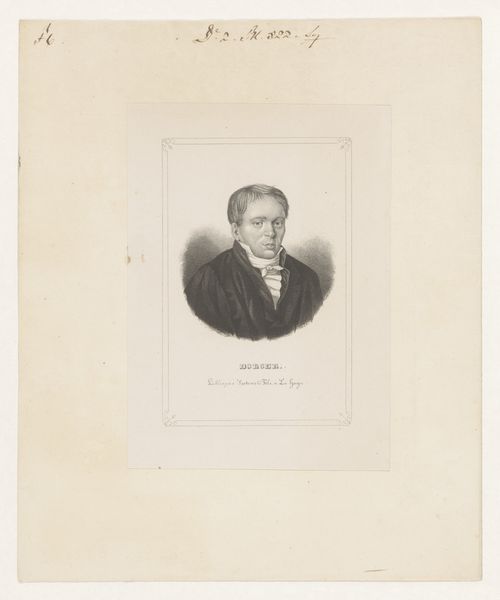

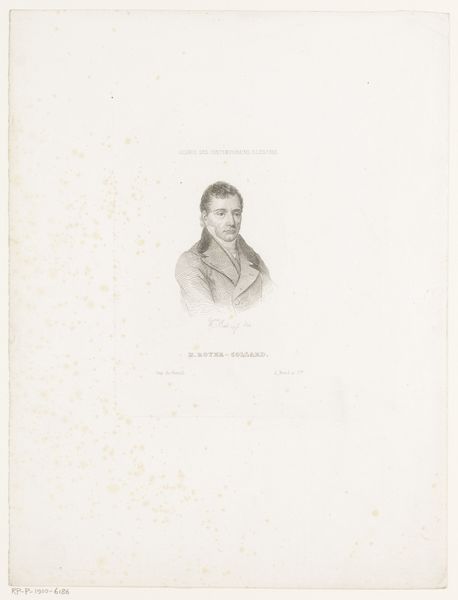

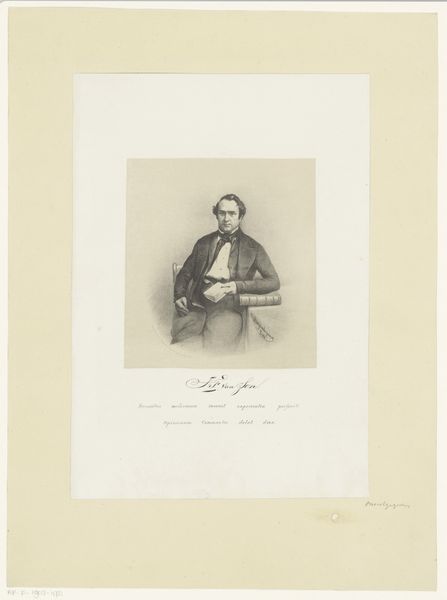

lithograph, print

#

portrait

#

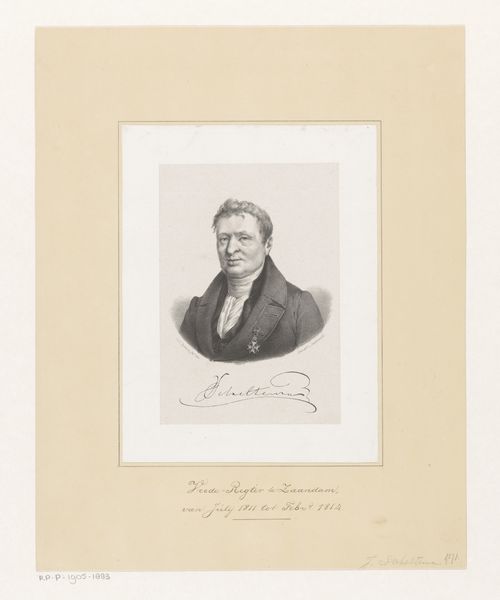

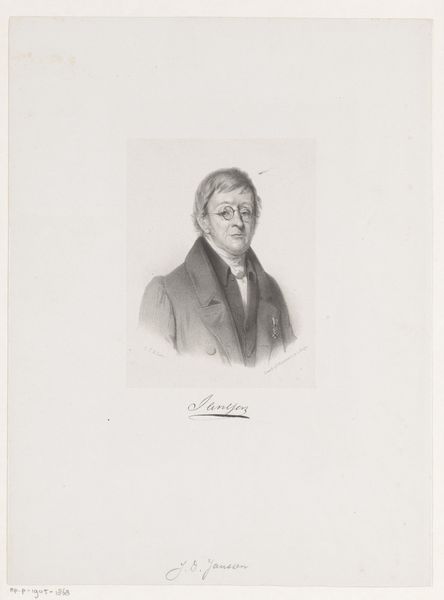

pencil drawn

#

lithograph

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: height 358 mm, width 271 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So here we have Leendert Springer's portrait of Johan Melchior Kemper, likely from around 1850. It’s a lithograph, which gives it this interesting…almost mass-produced feel. What do you see when you look at this portrait, beyond just the face? Curator: Well, immediately my focus goes to the lithographic process itself. Look at how the lines create the form; think about the labour involved in producing multiples of this image. Was this intended for widespread distribution, potentially democratizing access to Kemper’s image? That has significant social implications. Editor: That's interesting! I hadn't thought about the ‘mass-produced’ aspect as a deliberate choice, more just a consequence of the time. Curator: Exactly. And consider the materials: the type of stone, the inks used. Were they readily available? Did their cost influence the accessibility of the print? It speaks to a network of production and consumption tied to social standing and intellectual circles. The labour division would also have played a crucial role: Who drew the image on the stone? Who printed it? And who was consuming this image of Kemper? Editor: I guess I was so focused on it being a portrait that I overlooked all of that! What would a print like this be *for*? Curator: Portraits, particularly in print form, circulated power. Who owned a copy? What did its display communicate about the owner's relationship with Kemper’s values, or their social and political allegiances? Every choice – the paper, the ink, even the decision to produce it as a lithograph instead of a unique drawing – all point to the cultural function of this object. Editor: I never considered the choice of printing method as something that infused meaning itself! It’s made me rethink the whole idea of portraiture. Curator: Precisely! By considering the material conditions of its making, we see the portrait as more than just a representation. It becomes evidence of social networks, production practices, and power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.