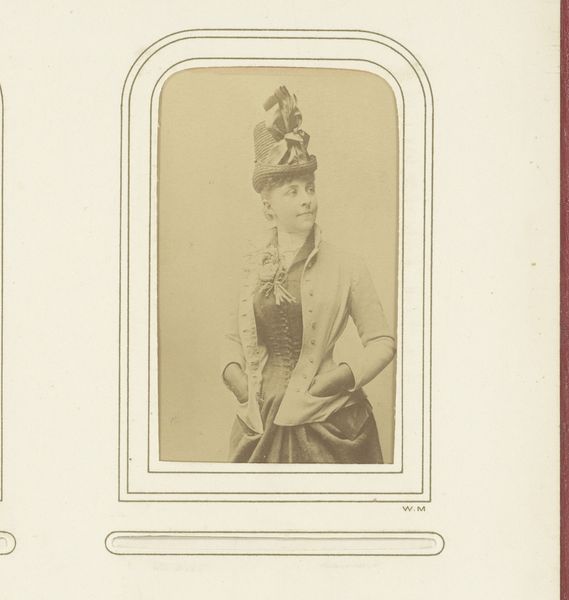

daguerreotype, photography, glass

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

glass

#

historical photography

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this image, I see celebration, a sense of release. It’s theatrical and inviting. Editor: Indeed. We’re looking at an intriguing photograph believed to be from around 1875 to 1885. It is titled "Portrait of Elisabeth Hjortberg in costume, with glass in hand.” It's captured using the daguerreotype technique, resulting in a direct positive image on a polished glass surface. Curator: Hjortberg is presented, for lack of a better term, en travesti; the choice to depict a female opera singer, specifically, in men's clothing is hardly coincidental. Editor: It certainly speaks volumes! Gender-bending was an accepted performance and popular cultural tradition then; roles in operas for younger male figures were, surprisingly often, portrayed by female opera singers, it would seem. Curator: Consider the imagery. What kind of gender roles might such visual displays signal in 19th century Europe? The high-held glass acts as a symbol of liberation. She wears men's attire but retains her delicate feminine grace. Editor: Exactly! Think about this specific theatrical lens to frame it; male or female, Hjortberg uses costume, gesture and stagecraft to embody an identity. Is this persona reflecting or refracting real attitudes about power, celebration, performance at the time? Curator: It’s worth mentioning that studio portraiture provided new platforms of visual self-fashioning among various performers. But in particular for queer people, that sort of public portrait had real world political consequences in many instances. Editor: And still does for that matter! It strikes me too, that she isn’t caught up in representing any *single* aspect of performance, identity, class. Perhaps her power as an artist comes precisely from weaving those together to project multiple things. Curator: It truly invites us to investigate gender and class as things performed. In these performances there’s freedom of reinvention in how Hjortberg is presented, which, upon examination, still reveals a bit of both 19th-century spectacle, and everyday experience. Editor: A perfect toast to art’s continuing ability to stir debate, while preserving beauty across the ages.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.