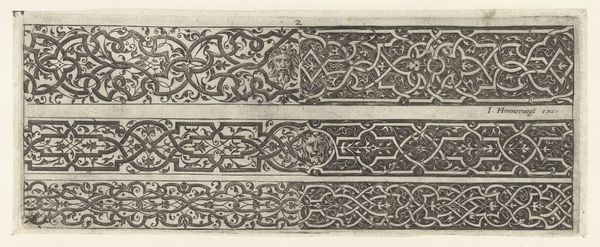

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

graphic-art

#

natural stone pattern

#

rippled sketch texture

# print

#

old engraving style

#

woodcut effect

#

crosshatching

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

embossed

#

limited contrast and shading

#

line

#

pen work

#

italian-renaissance

#

layered pattern

#

engraving

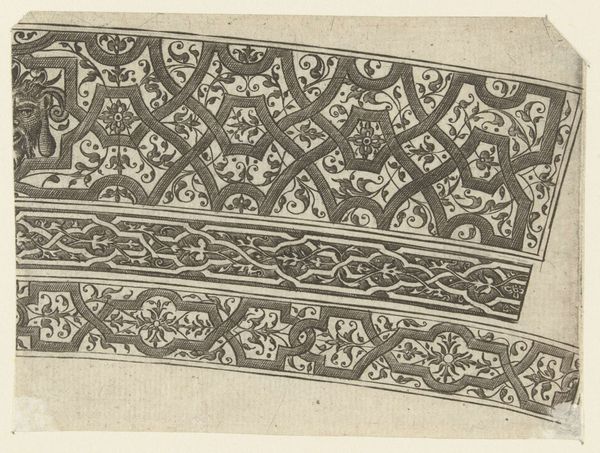

Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 227 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

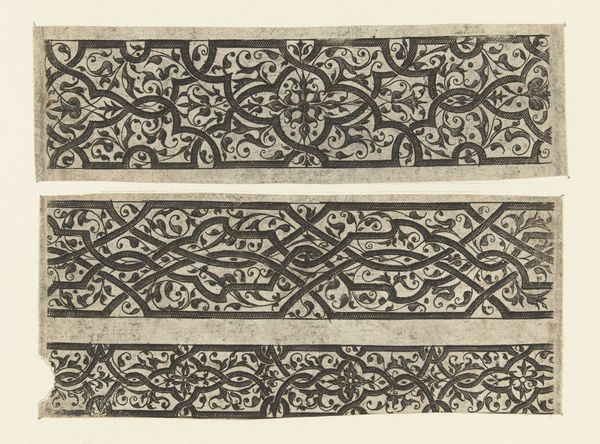

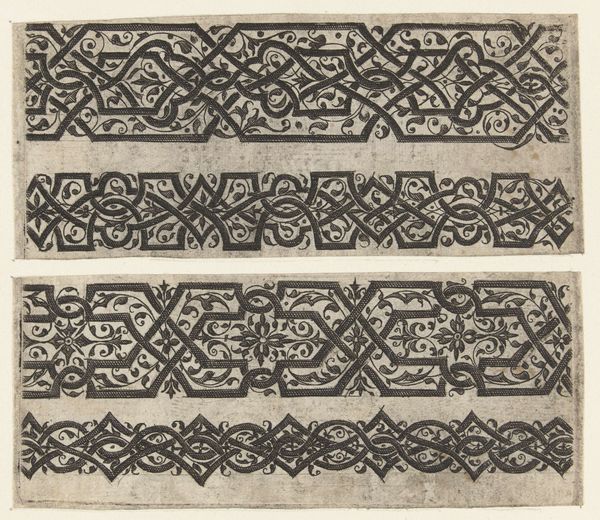

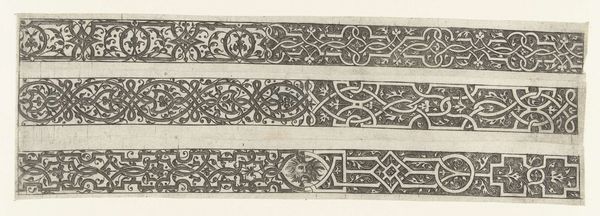

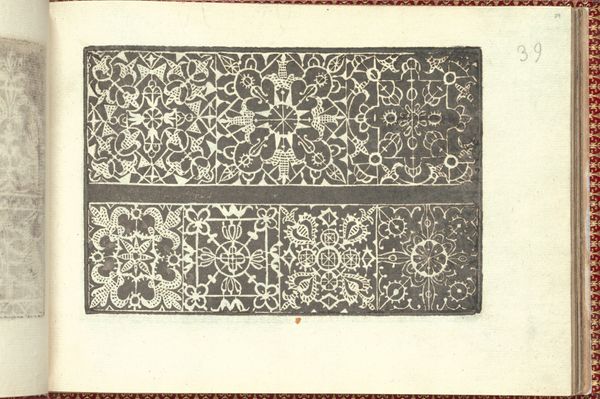

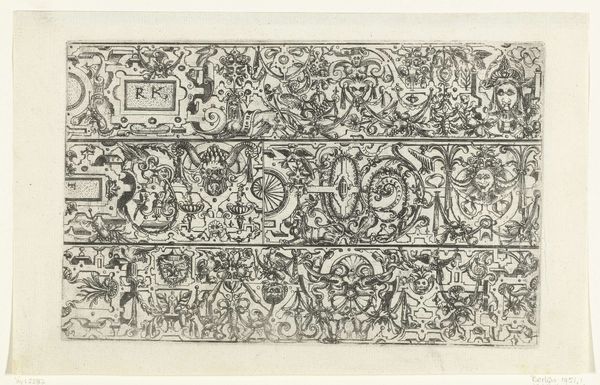

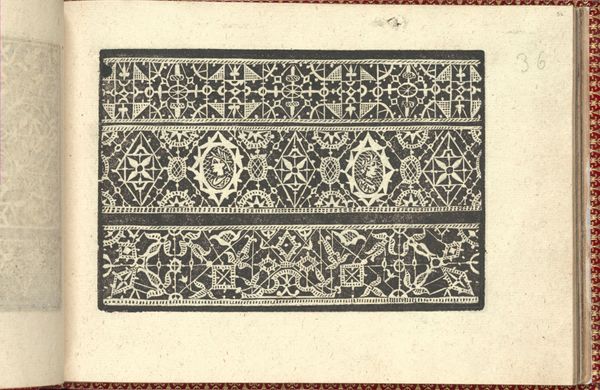

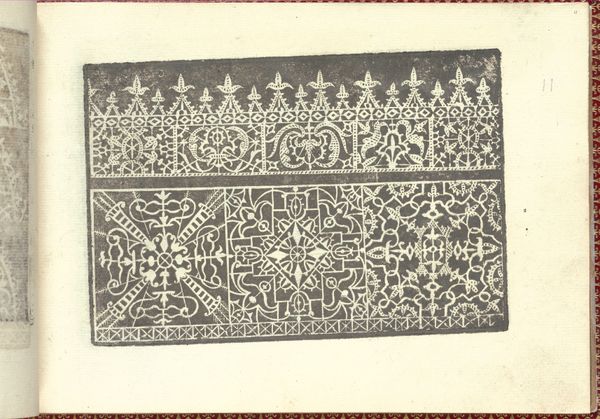

Curator: Look at the intricacy! Here we have "Een breed fries en twee smalle friezen met moresken," dating from between 1550 and 1580, held here at the Rijksmuseum. It's an engraving. Editor: It has such a decorative quality, almost overwhelming. A feast for the eyes. I see immediately a dense, interlacing design, repeated motifs – the lines so clean, like an ornamental script, but cold. Curator: The cool effect comes through, indeed. I understand this piece speaks volumes about the accessibility of art during that period. Engravings allowed for mass production, democratizing visual culture beyond the elite. Imagine these borders not just as adornments, but as tools for social climbing through fashionable displays! Editor: Absolutely. And we can't ignore the labor involved in producing such a print. Who were these artisans? Were they celebrated or considered mere craftsmen? Their skills were undeniably crucial to spreading design ideas and contributing to interior decoration. We would want to reflect on what printmaking afforded society. Curator: Excellent questions. It makes you think about who was designing these things, right? Were they even attributed in many instances? We know prints like these circulated widely as models for artisans, influencing everything from furniture to textiles. It played a critical role in establishing aesthetic standards and spreading Italian Renaissance ideals across Europe, it should also be noted. Editor: Yes, and the 'moresken', or moresque designs are themselves fascinating—borrowed and adapted from Islamic art, reflecting a complex cultural exchange and appropriation that often gets glossed over. We see the dynamics of power playing out even in these decorative forms, right? What does it mean when Western art adapts motifs rooted in another culture’s aesthetics? Curator: Precisely! These objects invite viewers to reconsider notions of authorship and value—how these images helped transform taste and aspiration among a growing middle class hungry for symbols of status in their domestic environments. Editor: So, it is fair to state that despite its detached affect and cold style, this piece has a dynamic history of production, and cultural adoption tied to larger historical shifts in economy and power! Curator: Right. It’s an intersection where aesthetic preferences collide with social ambitions. Editor: Which makes it all the more worthy of exploration, beyond its initial appeal as ornament.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.