photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

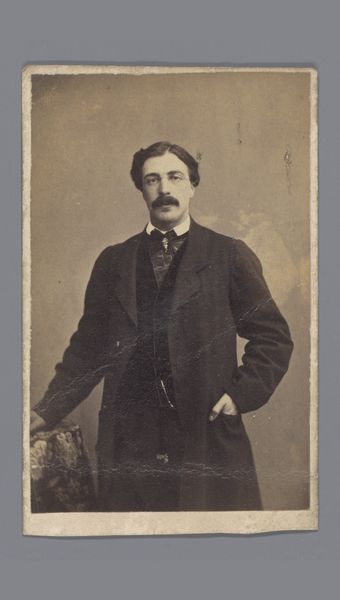

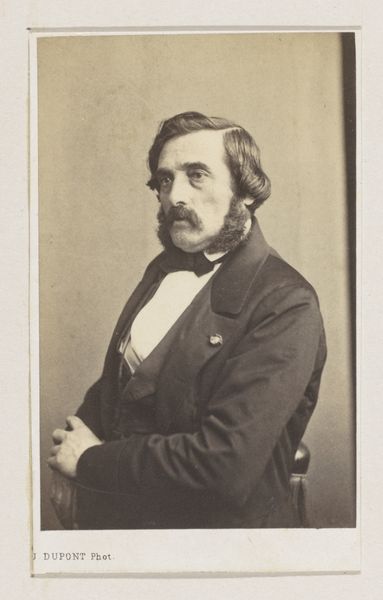

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

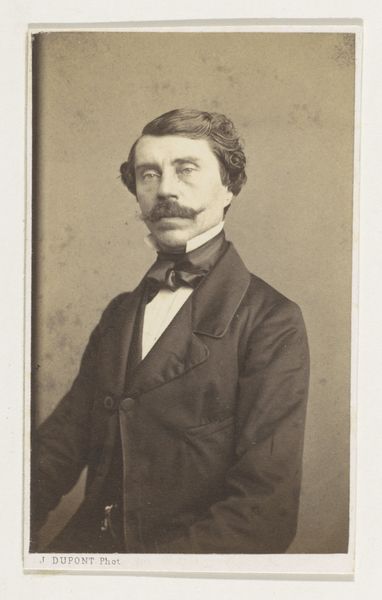

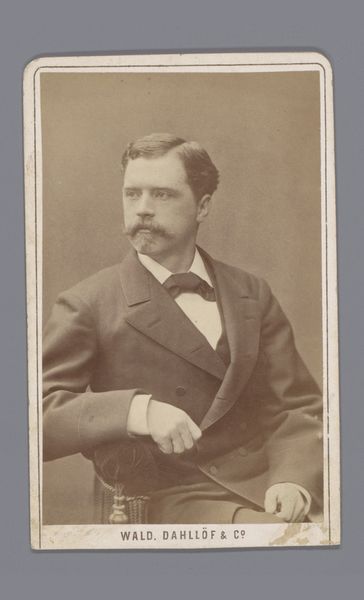

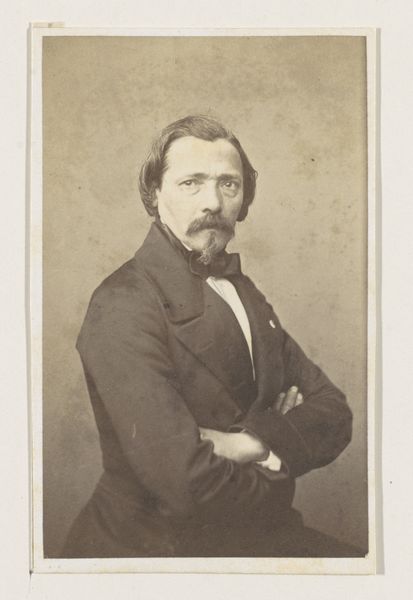

Curator: We’re looking at a portrait from 1861 by Joseph Dupont. It’s a gelatin-silver print titled “Portret van de schilder Moshelès, halffiguur"—a portrait of the painter Moshelès, half-length. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the materiality. Gelatin silver gives it a subtle sheen, but it’s the texture of his clothing, the crisp details of his vest, the very slight blur of the background—you can almost feel the surfaces. Curator: Photography was gaining momentum as a tool for portraiture at this time. Consider the rise of the middle class. Dupont provided an affordable option to painted portraits, impacting patronage structures within the arts. Editor: Right, access changed things, and with that the expectations around representation, too. Look how squarely he faces the camera. There is very little flourish. It's matter of fact. No flattering distractions, just… him. Curator: Exactly, that straightforwardness also speaks to the broader artistic movements. Realism was gaining ground; there was less emphasis on idealizing the sitter and more on presenting the person as they are. Editor: And what about the role of the photographer? We’re talking about this "realism," but this is still Dupont's selection of pose, lighting, focus... Curator: Yes! The power dynamics in these early photographic portraits were complex. While appearing objective, photography, just like painting, involved curatorial choices about how individuals and social classes were represented. These decisions could either challenge or uphold existing hierarchies. Editor: I appreciate that the photograph gives us such clarity and texture to observe these nuances; considering material changes helps inform a reading of how people were trying to picture themselves in an industrial era. Curator: Reflecting on the photograph’s capacity to democratize portraiture alongside social shifts really reframes how we understand both its artistic and historical contributions. Editor: Absolutely. It’s in these details—the materiality, the composition, the choices both sitter and artist made—where we truly connect with the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.