drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

ink painting

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 10 1/2 x 16 7/16 in. (26.67 x 41.75 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

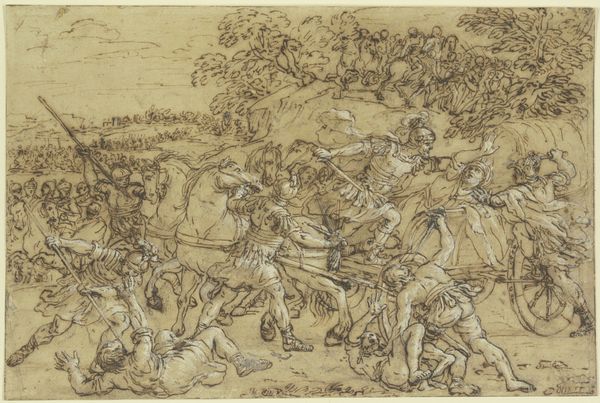

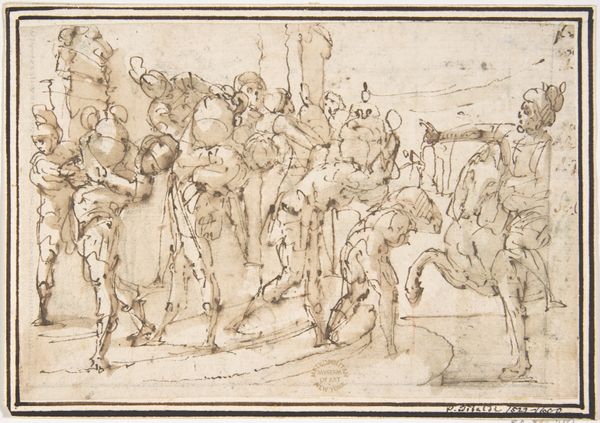

Curator: At first glance, this drawing appears frantic. The linework is so energized, there’s a palpable tension radiating from it. Editor: That's a fantastic observation. What we’re seeing here is Gaspare Diziani’s “Mucius Scaevola Before Porsena,” an ink drawing dating from the 1740s, depicting a pivotal scene from Roman history. It's currently part of the Minneapolis Institute of Art's collection. Curator: Ink work makes complete sense to me; look how thinly spread the ink is on the surface! It looks more sketched than drawn, really playing into this effect of action. I almost get the sense that this was done on site. What kind of political circumstances drove the distribution of history paintings like this, at the time? Editor: Well, the story of Mucius Scaevola was incredibly popular during periods of war and upheaval. His defiant act of self-sacrifice served as a potent symbol of Roman courage and patriotism. These kinds of artworks acted as visual propaganda. And with this piece existing in ink, and at this scale, you can start to imagine it mass-produced, or studied for much grander compositions. Curator: The material’s scale does indeed bring a sense of urgency. And even beyond that historical narrative, the textures themselves contribute to the drawing’s message, the dynamism lending credibility to Mucius' bravery. How might the art world have approached the subject if oil paint was the clear expectation? Editor: Had this subject been rendered in oil on a much grander scale, it would signify an establishment position, an appeal to a specific aristocratic class or government. Because this sketch carries the Baroque influence with that dynamic quality you highlighted earlier, you would imagine something more academic, which wouldn’t necessarily align with the revolutionary ideas linked with this narrative! The turn to a more intimate medium underscores its potential accessibility, broadening its societal impact. Curator: That makes perfect sense. Thinking about it materially provides context to the grandiosity of that moment. Editor: Yes, exactly! Looking at Diziani's choice to employ ink allowed us to examine the production and potential distribution of the image, enriching our grasp on the potent influence artworks wielded at pivotal moments. Curator: Thinking about Diziani’s piece and the potential ways ink opens the conversation around production, I better understand its contemporary relevance.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The ancient story of Mucius Scaevola was a popular subject in 17th and 18th-century Italian art. When the ancient city of Rome was under attack by Etruscan troops, a young Roman nobleman Mucius snuck into the enemy camp to kill the invading army's king, Porsena. Mucius, however, was seized after killing the king's secretary by mistake. Indifferent to his seemingly sealed fate, Mucius sacrificed his right hand in front of Porsena and his men, shoving it into a fire. The king was so impressed by his bravery, he set him free, and the young hero was henceforce called "Scaevola" or left-handed. This compositional study had no attribution when it arrived at the museum. It borrows heavily from Raphael's famous Sacrifice of Lystra, one of the Sistine tapestry designs Raphael executed in 1515, which made it difficult to recognize the hand of the artist. Yet it seems likely to be by prolific and accomplished 18th-century Venetian draftsman Gaspare Diziani, as has recently been suggested by the scholar George Knox. The energetic, almost frantic penwork, the planar compositional format, the figure types and costuming are all consistent with his drawing style, and he favored this combination of media for large compositional studies, that is, pen and ink over red chalk.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.