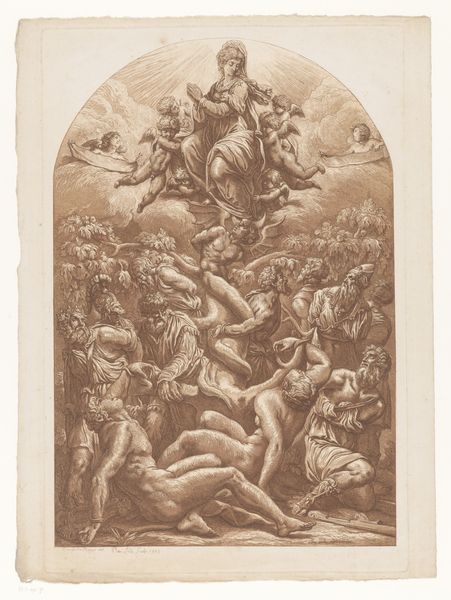

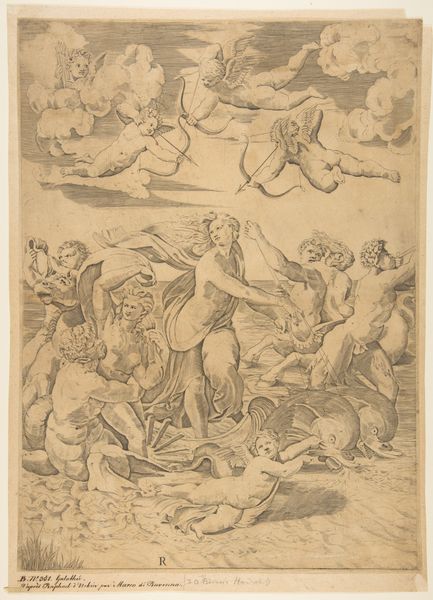

Allegory of the Immaculate Conception, with Adam, Eve, kings, priest, soldier and Moses tied at the bottom of a fig tree, and the Virgin sitting on cloud overhead, surrounded by angels 1611 - 1612

0:00

0:00

drawing, print

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

coloured pencil

#

pen-ink sketch

#

mixed medium

#

sketchbook art

#

pencil art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: Sheet: 20 9/16 × 14 1/2 in. (52.2 × 36.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have "Allegory of the Immaculate Conception," made between 1611 and 1612 by Philippe Thomassin. It's a print—a drawing, really—on toned paper. I'm struck by the sheer density of figures; they seem packed together. What speaks to you most when you look at it? Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the materials themselves and their implications. It's a print, widely reproducible. This shifts the emphasis from singular artistic genius to the dispersal of an idea, a commodity even. Consider the socio-political context: How does the mass production of religious imagery reinforce or challenge existing power structures? Editor: That's fascinating. It wasn’t a unique artwork, which I hadn't thought about! Does the medium itself then contribute to the artwork's message? Curator: Absolutely! The act of printing transforms the image from a singular, precious object into something accessible. What materials do you think may have been employed? What do you make of the pencil and ink’s contribution? Consider the paper: its availability, cost, its specific preparation to function in contrast to the mediums, etc. Who would've been able to afford this print, and where would it have been displayed? These questions ground our interpretation in the material realities of its time. Editor: So, understanding the economic and social context is key to truly understanding the art. It makes you wonder how we consume art now versus then, too. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on production, consumption, and the social implications of these prints, we gain insight into the beliefs circulating and how such material objects reinforced those beliefs. We challenge the usual focus on high art and start to look at how art can impact society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.