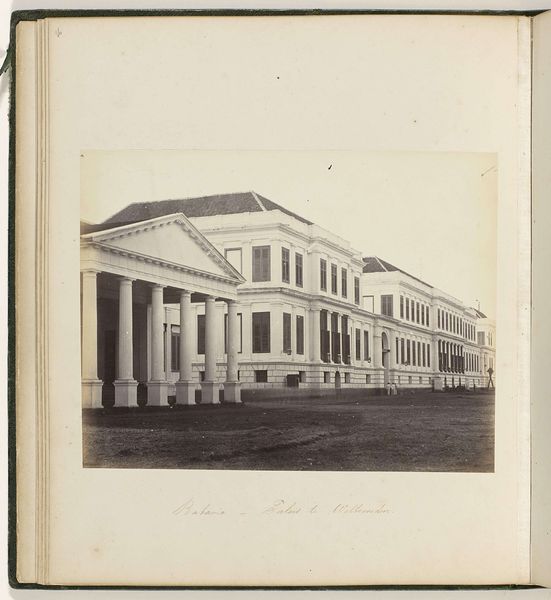

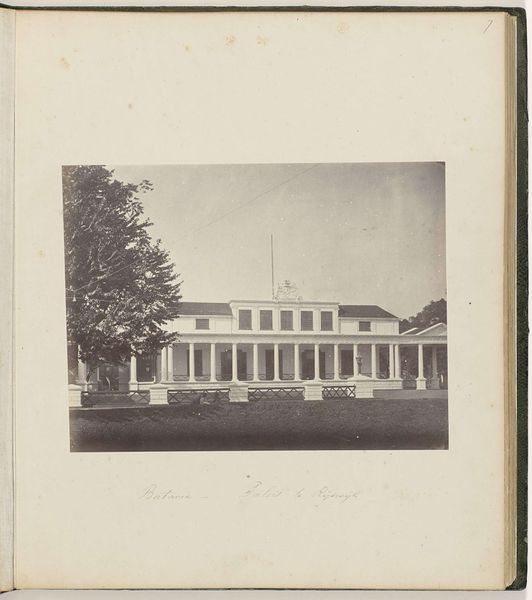

photography, albumen-print

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 186 mm, width 242 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So this albumen print from around 1863-1866, titled "Batavia - Maclaine Watson & Co," and attributed to Woodbury & Page… it's this almost ethereal cityscape, isn't it? The building dominates, yet the figures gathered feel…muted, ghostly, practically swallowed by the architecture. What stories do you think it whispers? Curator: Ah, whispers… indeed. It doesn't scream, does it? It's more like a hesitant sigh, captured in sepia tones. For me, it conjures a moment suspended in time, where commerce and colonial ambition intertwine with the daily lives unfolding beneath that impressive facade. Do you see the carriages? The way the figures are arranged? There’s a sense of…performance, wouldn’t you say? Almost staged. I wonder, was this intended to project a certain image of Batavia, a booming colonial city? Or is it simply a straightforward documentation of place and time? Perhaps both? Editor: "Performance" is interesting. Like, consciously constructed. And, perhaps the slight blur contributes...Was the exposure time much longer back then? Curator: Absolutely. This process of collodion printing requires a lot of light and stable conditions which made people still, but gives an "honest" image. I keep getting drawn to those arched colonnades – echoing the authority and perceived grandeur. I imagine them filled with bustling activity, yet the image itself feels so…still. It reminds me that photography can both capture and curate a reality, selectively emphasizing aspects of life. What do you think the contrast between the solid architecture and less-defined surroundings convey to the contemporary observer? Editor: It kind of boxes up and contains the people into this space. I didn’t quite notice the…imperial gaze behind it, you know? The company's goal of promoting business, creating trade in the East Indies – it makes more sense with what you’re saying! Curator: Precisely! The camera becomes a tool in service of empire. A quiet propagandist, framing a specific narrative. That slight blur? Maybe it's not just technical, maybe it suggests that all stories, especially those seen through a colonial lens, are open to reinterpretation! So grateful for the fresh, curious way you look at the world, opening new ways to see the history of colonialism with all its cultural meanings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.