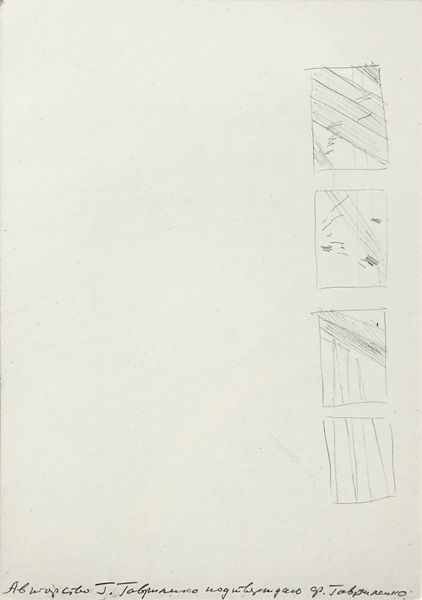

Dimensions: support, each: 560 x 768 mm

Copyright: © The estate of Bob Law | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

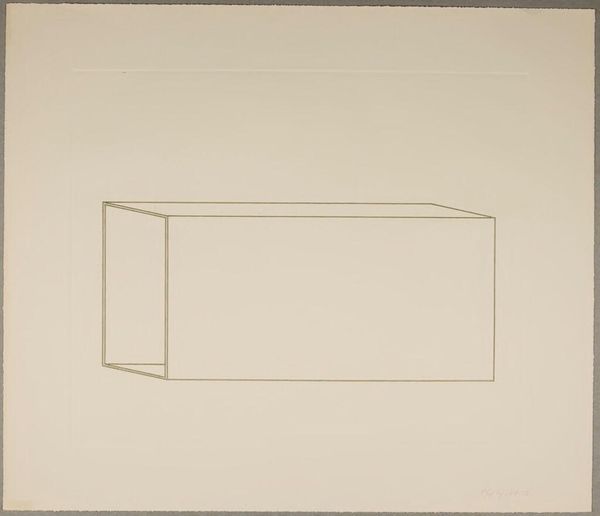

Editor: This is Bob Law’s "Twentieth Century Ikon Series 8.8.67" made in 1967. It's deceptively simple, just a few lines, yet it feels monumental. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This work challenges the very notion of the 'icon'. In 1967, when minimalist art interrogated power structures, Law asks: what does it mean to create an 'icon' in a world oversaturated with images and ideologies? Is it an assertion of the self? Editor: So, it's not just about the lines, but about questioning what we value? Curator: Precisely. The simplicity itself becomes a statement, resisting easy consumption and demanding critical engagement. It forces us to ask: what icons do we create, and who benefits? Editor: I never thought of minimalism as a form of resistance. This gives me a lot to think about. Curator: It's a reminder that even the most austere forms can carry profound social commentary.

Comments

tate 9 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/law-twentieth-century-ikon-series-8867-t12177

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

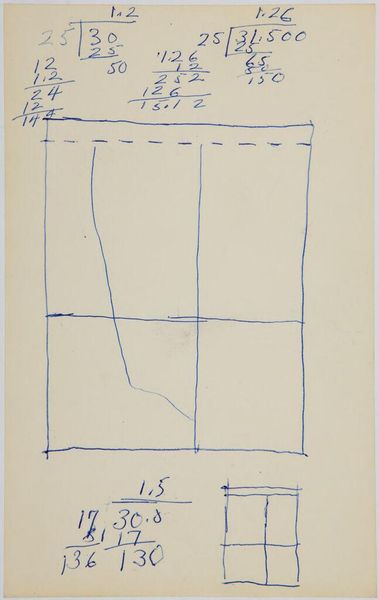

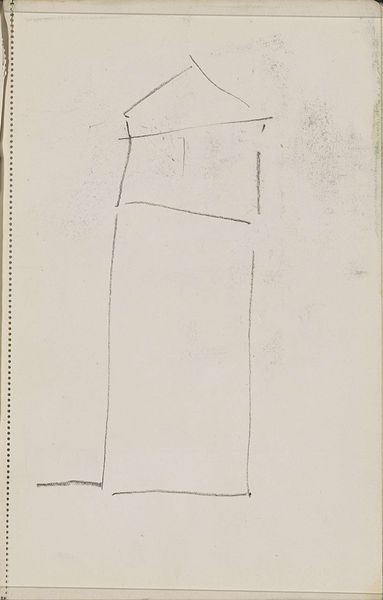

This series of nine drawings on paper was executed over the course of a single day. A penciled inscription in the lower right corner of each drawing reveals the sequence of the series – given as a roman numeral – and the date of completion, as well as providing a means of orientation. Executed as scant, exploratory variations of the same scheme, in the first drawing three rectangles of space approximating a golden ratio of proportions are delineated within a rhomboid graphite line framing almost the entire expanse of the paper. In the second and third drawings in the series the established horizon line gradually sinks along the vertical axis such that the smaller supporting rectangles shrink in size; for the subsequent three drawings the page is portrait-oriented and the horizon climbs, shuttling the smaller rectangular spaces towards the top edge; and for the final three landscape-oriented drawings the horizon sinks again, pressing the largest rectangle of space downwards. Precisely because of these shifts and reorientation of ground, the series together imparts an overall sense of movement – a cycle charting the artist’s changing perspective. For the most part, Law’s lines are of a single, slightly variable thickness and have been drawn without a straightedge, grid or other rigid structuring device; the persistent vertical lean of his outlines has been ascribed to swift right-handed drawing.