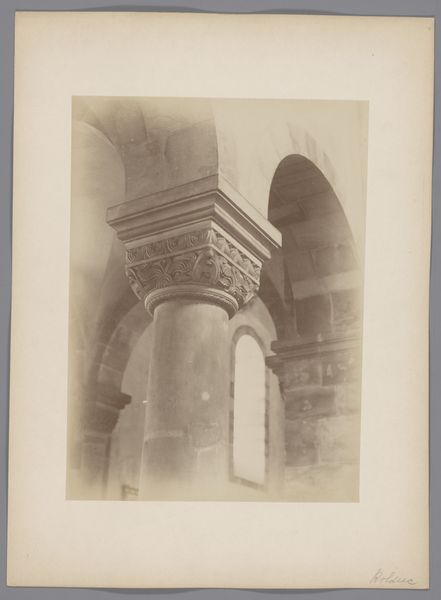

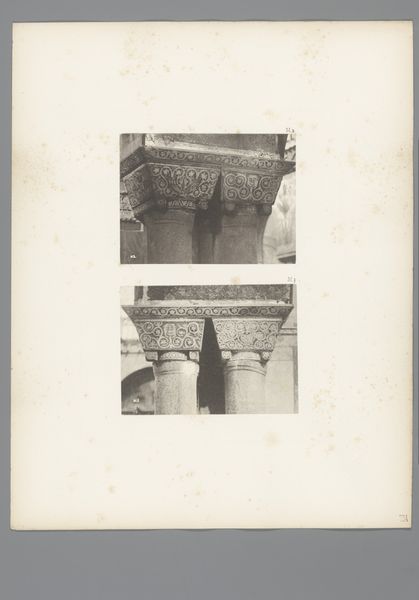

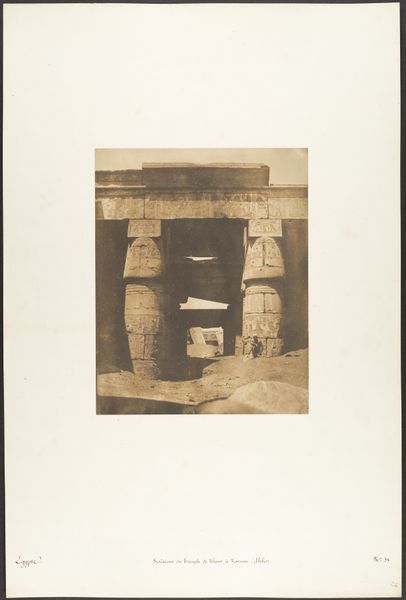

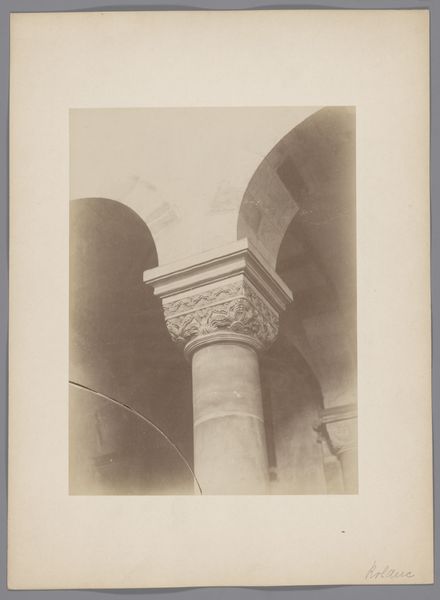

carving, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

carving

#

muted colour palette

#

landscape

#

white palette

#

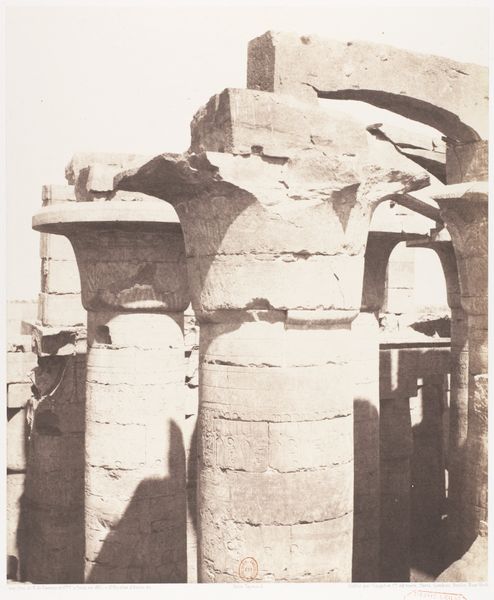

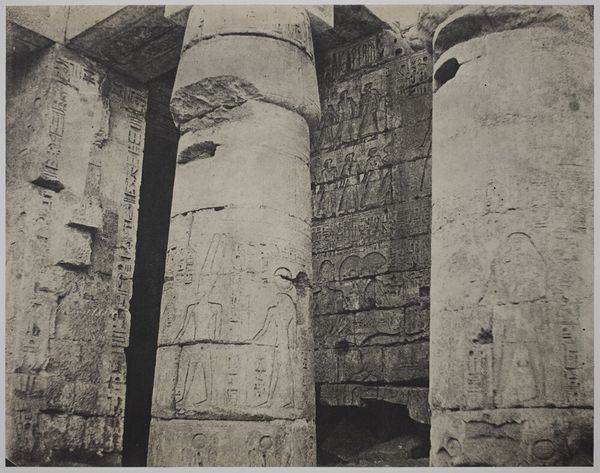

ancient-egyptian-art

#

figuration

#

photography

#

unrealistic statue

#

carved into stone

#

column

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 288 mm, width 234 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin silver print, captured sometime between 1875 and 1900 by Maison Bonfils, showcases a column within the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. It's a fascinating example of early photographic documentation blending with Orientalist aesthetics. Editor: It’s like stepping back in time... yet the first thing that strikes me is this looming, almost ghostly presence. The column is majestic but muted, as if holding secrets for centuries, trapped within the toned paper itself. Curator: Exactly. The Temple of Hathor, dedicated to the goddess of love, beauty, and music, holds significant cultural weight. Bonfils's lens offers a view into a space of immense symbolic value, but simultaneously mediates that space through the lens of the 19th century’s colonial gaze. The carving, the hieroglyphs...they’re all framed within this European fascination with the "exotic" Orient. Editor: Absolutely. I am drawn to the faces on the column; they appear to be both watching us and guarding the knowledge from a lost world. But also, the sepia tone makes everything seem ancient and slightly detached. Almost like looking at a faded memory of the actual location. Curator: That's precisely where the photograph's tension lies, doesn’t it? On the one hand, photography offers an ostensibly objective record, yet the choices made – framing, lighting, the very act of selection – reveal so much about the photographer’s, and indeed, the era's worldview. The photograph is less about pure documentation and more about representation and power dynamics. Editor: True! It reminds me how history and representation are intrinsically linked, and it’s not merely a 'snapshot'. Each picture tells not only of an ancient Temple and a Goddess, but also it reveals stories of how we view "otherness", stories we have written ourselves, like another layer of glyphs. I suppose. Curator: It is through recognizing those embedded layers that we can move towards more equitable and decolonized ways of interpreting historical artworks. Editor: I love how art, even a photograph from over a century ago, can be such a living invitation to look at both what’s "then", but also who and where we are right now. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.