drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ink

#

cityscape

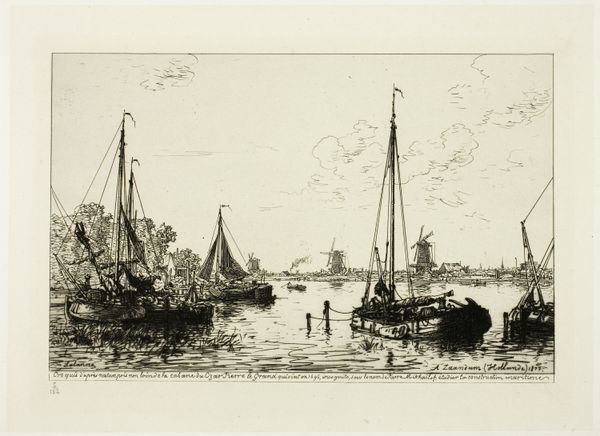

Dimensions: image: 20.9 × 30.5 cm (8 1/4 × 12 in.) sheet: 38 × 53 cm (14 15/16 × 20 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This is Maxime Lalanne's "A Haarlem," an etching created in 1877. Editor: It's quite evocative! Immediately, I'm struck by the contrast between the detailed foreground and the more faintly sketched background, and it creates a wistful, almost nostalgic feeling. Curator: Lalanne, like many artists of the time, was deeply interested in the revival of etching as a serious art form, focusing on the printmaking process and technical mastery involved. You can really see it here, I think, in the intricacy of the linework—it feels almost photographic despite being entirely hand-crafted. Consider the labor needed to produce the plate itself; that’s essential to understanding the image, and the time required to print it is equally valuable. Editor: Absolutely. And what strikes me further is how it captures Haarlem in a moment of transition. You have the prominent windmill—a symbol of Dutch industrial power of the past. Consider it in dialogue with the other emergent urban signs that populate the image, specifically what is enabled by its waters, namely movement of goods and, thereby, global capital. Curator: And beyond mere depictions, prints were readily available and affordable—the printing press democratized image consumption and, by extension, access to the aesthetic dimensions of representation that had until then been reserved for only wealthy landowners who could buy originals. Editor: Exactly. Think, too, about the politics inherent in the gaze. Lalanne chooses a scene of relative tranquility. This says something about the priorities and biases involved in crafting idyllic scenes that reflect cultural memory. There were obviously other stories he could have chosen to reflect here. Curator: I agree there are politics to unpack here. However, the success of a work like "A Haarlem" also resided in the very direct relationship between the maker and the print. The artist creates the printing plates, monitors the output, and is ultimately the producer and the seller. They maintain far more agency over the commercial aspects of their works. Editor: Fascinating to consider all of this layered together. It makes you think about how deeply implicated this quiet waterside view is within larger networks of labor, production, and politics. Curator: I think it highlights the importance of understanding the process of art-making when assessing even a seemingly simple cityscape like this one. Editor: Precisely. Looking again with this framework, it reveals a more profound commentary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.