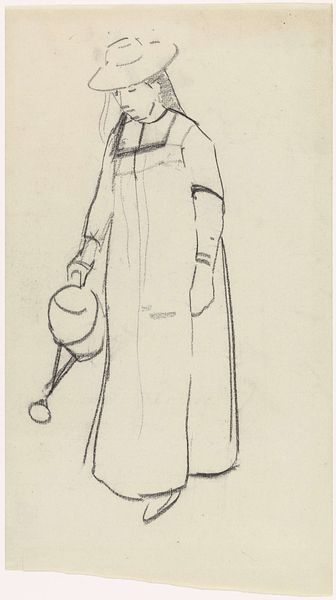

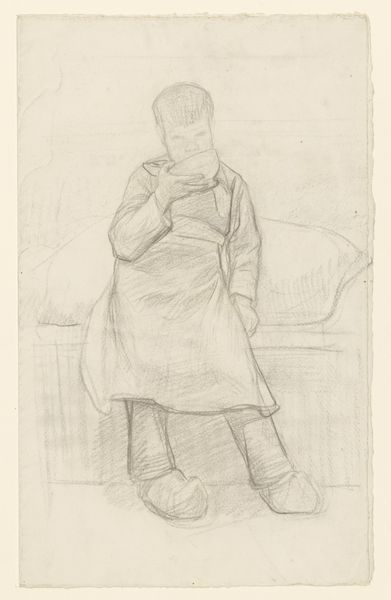

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

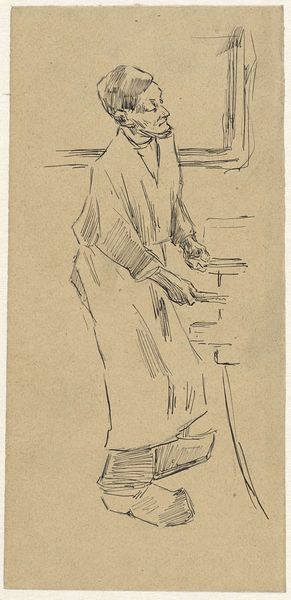

Dimensions: height 333 mm, width 214 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find the mood rather somber, even with such a simple composition and soft execution. What's your initial read? Editor: The drawing evokes a quiet, weighty sense of everyday struggle and resignation, like this is just how life is and he can not imagine other possibilities. It certainly pulls the eye and touches my heart. Curator: Indeed. The piece you’re looking at is a drawing titled "Fabrieksjongen aan het werk," which translates to "Factory Boy at Work." Created sometime between 1868 and 1892 by Anthon Gerhard Alexander van Rappard, it offers insight into a stark reality of that period. The artwork consists of pencil on paper. Editor: Rappard's choice to depict this factory worker, presumably a young boy, feels significant, doesn't it? What symbols do we perceive, looking beyond the aesthetic simplicity? Curator: Absolutely. Rappard belonged to a generation of artists who turned their gaze toward social issues, particularly the lives of the working class. This was during the rise of industrialization and its often brutal impact on families and children, a situation captured by other contemporary authors and social reformers as well. It reflected, and perhaps further fueled, a rising awareness of social injustice and a desire for change. Editor: The wooden shoes, for example, are immediately recognizable as symbols of a certain rural, working-class identity. Is he trying to send a deeper message by emphasizing his provincial looks in this sketch? Curator: I think it is safe to suppose so, especially when we consider Rappard’s social-realist artistic leanings and circles. In Dutch culture, such footwear was traditionally associated with laborers and rural life. By including them, Rappard may be emphasizing the boy's humble origins and lack of social mobility. They also serve as a visual shorthand, instantly placing him within a particular social context. The downward glance of the child also echoes themes of weariness and societal imbalance. Editor: Ultimately, I think this drawing resonates so strongly because it taps into a timeless theme of youth robbed of innocence, the exploitation of labor, and the unequal societal structures that perpetuate it all. It's a small work but manages to carry a considerable burden. Curator: I agree entirely. Rappard's sketch isn't merely a portrait; it's a historical document that invites us to reflect on the complexities of progress and the human cost it often demands, issues that, depressingly, continue to hold weight today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.