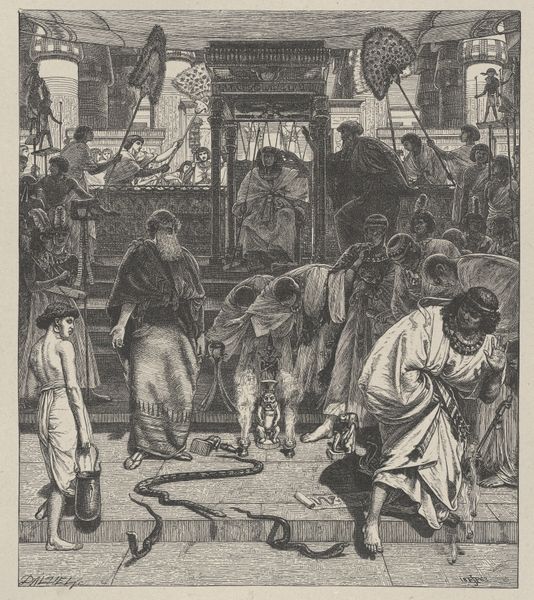

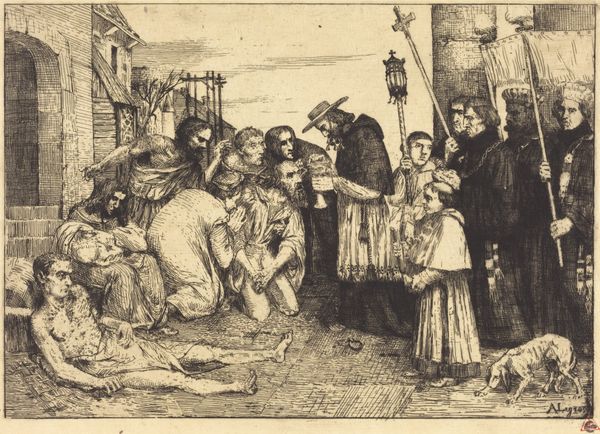

The Parable of the Prodigal Son, No. II: In Foreign Climes 1882

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

impressionism

#

etching

#

orientalism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 20 3/16 x 24 7/8 in. (51.2 x 63.2 cm) plate: 12 5/8 x 15 3/16 in. (32 x 38.5 cm) frame: 24 1/2 x 30 1/2 in. (62.2 x 77.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have James Tissot's etching, "The Parable of the Prodigal Son, No. II: In Foreign Climes," created in 1882. Editor: My immediate impression is one of tension—almost a sinister decadence. The figures seem caught between revelry and a looming sense of unease. The light feels artificial, trapped within those lanterns. Curator: Tissot situates the biblical story of the prodigal son within a decidedly Japoniste setting, reflecting the Victorian era's fascination with East Asian aesthetics and culture, particularly in artistic circles. This choice isn't merely decorative. How does that location speak to the narrative itself? Editor: Well, the use of Japan, though visually intriguing, plays into orientalist tropes prevalent at the time, othering and exoticizing the location as a place of moral laxity. This reinforces problematic power dynamics, casting the West as inherently virtuous in contrast. Were other marginalized cultures portrayed in his works in the same vein? Curator: Often yes. Tissot moved between London and Paris art circles which embraced Academic painting. The "flavor" he added was by recasting biblical and contemporary scenes to appeal to that sense of exoticism. The etching method allowed a wide distribution to bourgeois homes wanting religious art that also kept them aware of current cultural trends. Editor: You are suggesting a critique of bourgeois values embedded within the narrative itself? The prodigal son, framed by these Japanese motifs, can be seen as a symbol of Western decadence and its consequences. But perhaps, we might interpret those lantern lights not as symbols of superficial fun, but perhaps of yearning for real joy? Or safety within a tight community that can keep you out of trouble? Curator: It is easy to apply those ideas in retrospect. At the time, that was not how society viewed itself or interpreted the images it embraced. That does raise interesting questions about his artistic choices though—consciously or unconsciously mirroring or perhaps satirizing colonial attitudes and internal anxieties? Editor: Absolutely, and analyzing the image's reception then versus now highlights the shifting cultural and ethical lenses we bring to art. Examining who benefitted and who was othered through his artwork is of high importance today. Curator: Thank you. This has certainly encouraged us to reconsider Tissot's engagement with not just visual culture but also his representation of power dynamics in a colonial context. Editor: And to remember that visual pleasure, if it relies on exploiting and exotifying marginalized people, it can never be seen as truly pleasurable or valuable.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.