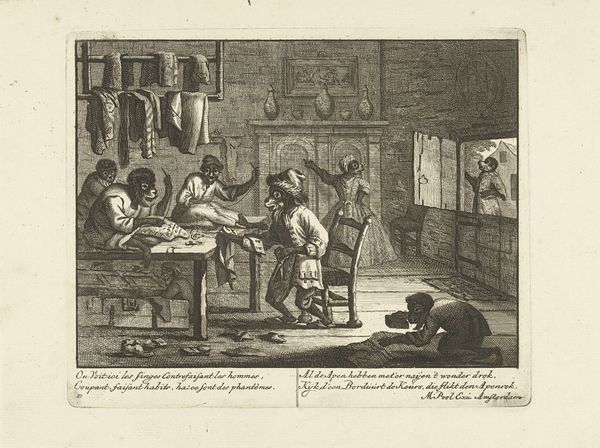

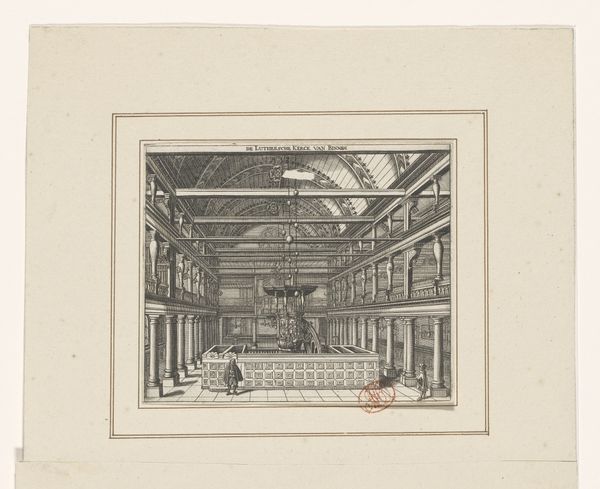

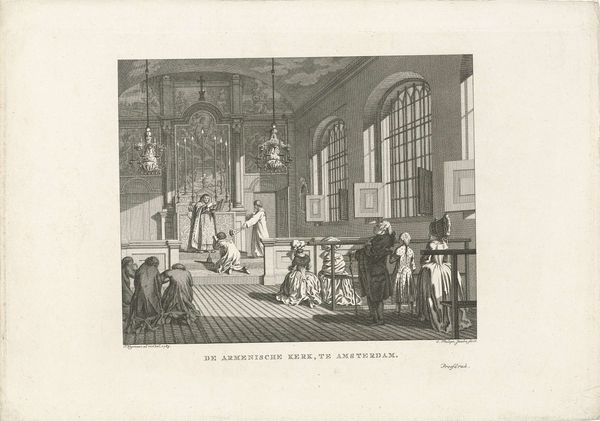

print, engraving

# print

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 223 mm, width 304 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The work before us, titled "Vergadering van Quakers" or "Meeting of Quakers," crafted around 1780 by Caspar Jacobsz. Philips, offers a glimpse into a Quaker gathering in Amsterdam. It's an engraving, so the details are meticulously rendered in lines. Editor: The first thing I notice is the muted stillness. There's something incredibly contemplative about the composition. The linear structure emphasizes the austere architectural setting, which serves to emphasize the focus and perhaps confinement, but also communal focus within the group gathered here. Curator: Yes, the linear style really suits the Quaker aesthetic. Their emphasis on simplicity, inner reflection, and rejection of outward display is mirrored in Philips' stylistic choices. The architectural space itself, flooded with natural light, becomes almost a character. Note how Philips utilizes light and shadow not only to give depth, but to offer what feels like emotional and symbolic significance here. Editor: That's a great point. The light highlights the diverse ways the participants engage. Some sit facing each other, deep in what we presume are serious conversations, while others appear more solitary, reflective even in a shared space. Are we really seeing them as they are? Are the gazes focused or internal? What does this scene reveal about visibility versus invisibility for marginalized communities like the Quakers? Curator: The very act of depicting them feels significant, doesn't it? By 1780, the Quakers had become a notable presence, but not without facing their share of scrutiny and prejudice. The artist uses realism to record this specific assembly and their customs; however, this work becomes significant as visual documentation of cultural practices. And if you think about symbolism more deeply, light frequently symbolized “Truth” which was very aligned with the Quakers. Editor: I think that visual document function makes this work incredibly important to acknowledge, not just because it records Quaker traditions, but it serves as an accessible mode of visualizing marginalized histories. This act is a step toward greater inclusivity. How can art shift the focus towards stories previously pushed to the margins of history? Curator: Exactly! It urges us to delve beyond the familiar narratives and engage with those of groups like the Quakers, understanding how visual imagery, and especially the way groups like the Quakers approached aesthetics can teach us a lot about values. Editor: I'm left contemplating what this moment captured by Philips signifies for contemporary dialogue—not just on religious tolerance, but representation itself. Curator: Indeed, it prompts a deep reflection on our perception of identity and community in our current context, which, is perhaps, its most important contribution to today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.