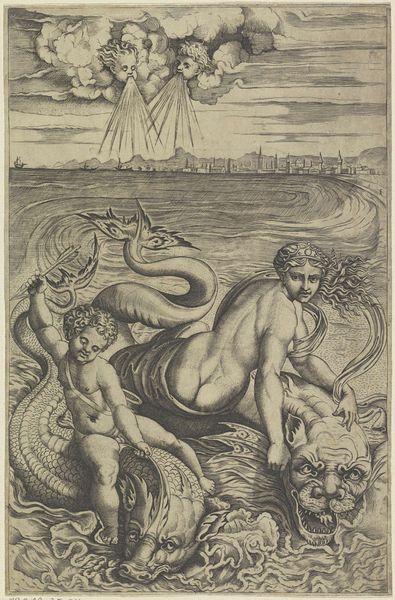

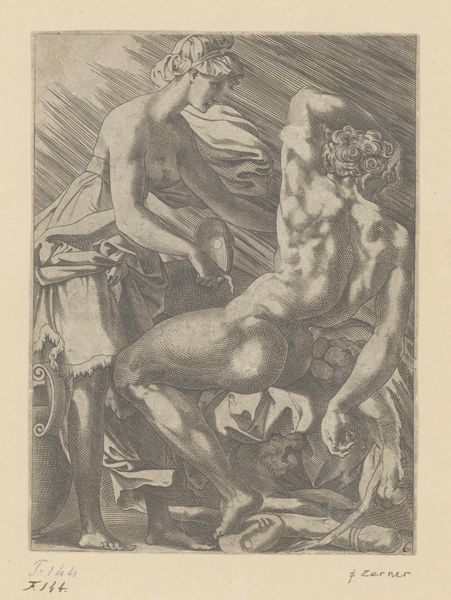

Venus and Cupid riding two sea monsters, Cupid raises an arrow in his right hand, two heads representing wind in the clouds above 1510 - 1532

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 10 7/16 × 6 13/16 in. (26.5 × 17.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This engraving, attributed to Marco Dente and dating from around 1510 to 1532, depicts Venus and Cupid riding two sea monsters. It's currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first thought? This is a powerfully weird image. There’s an unsettling tension between the idealised figures and the grotesque sea creatures, set against a vaguely threatening, windswept background. It feels strangely unbalanced. Curator: The tension is palpable. Note the engraving technique—the labor involved in creating the densely cross-hatched lines to build up tone and texture. Consider the specialized skill required to render flesh and sea monsters with equal detail. Also note how printmaking allowed for the wide distribution of images and ideas during the Renaissance. Editor: Absolutely. And in the context of that period, the nudity immediately brings classical mythology and its attendant politics of the body to the fore. Venus, as the embodiment of beauty and desire, is quite literally riding on these powerful, almost monstrous forces. What statement might Dente be making about the nature of female power or the negotiation of desire in Renaissance society? Curator: Well, allegorically, it shows that Venus, through love embodied by Cupid, can dominate even the most dangerous instincts—those wild "sea monsters." This print served a decorative or didactic function. The materials are relatively simple, just ink on paper. Editor: That's fair, though I can't help thinking about how the print medium itself democratizes the image of a goddess. Printmaking creates the means to subvert the dominant forms, by spreading images, perhaps enabling diverse and subversive readings, in ways not fully controllable by the artist or the elite. Who was really consuming these prints, and what kinds of interpretations did they bring? Curator: It highlights, nonetheless, the impressive craftsmanship of Italian printmakers during the early 16th century. I wonder if our modern ideas of mass production diminish our ability to truly appreciate the craft of this era. Editor: Agreed. By looking beyond art history, one can appreciate not just the visual spectacle, but also the social lives this image might have enabled. This piece acts as a launchpad into those histories. Curator: An excellent perspective, I had not considered all these potential views. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.