daguerreotype, photography

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

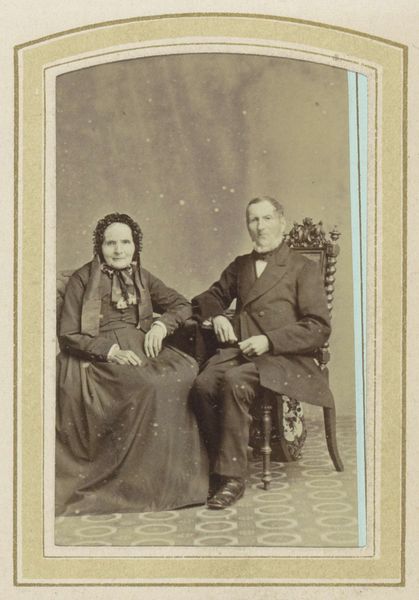

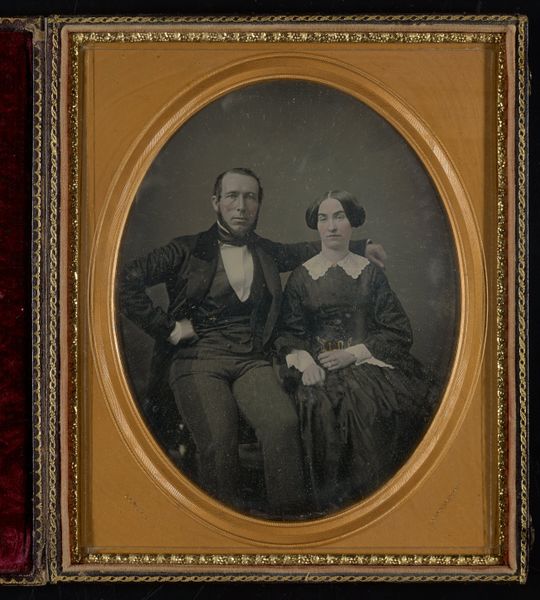

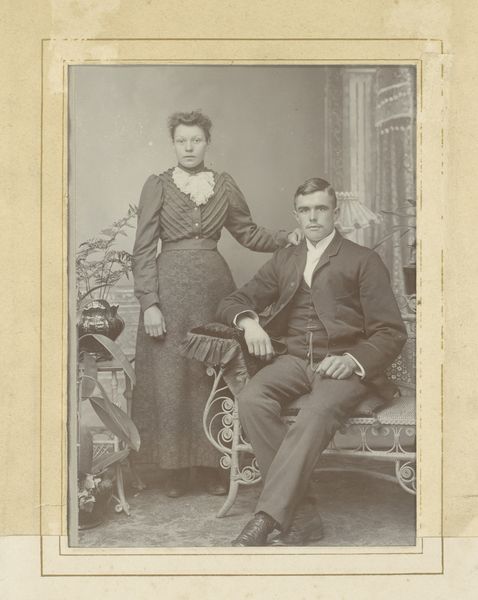

Dimensions: image (visible): 8.9 × 6.5 cm (3 1/2 × 2 9/16 in.) mat: 10.7 × 8.1 cm (4 3/16 × 3 3/16 in.) case (closed): 12.1 × 9.84 × 2.06 cm (4 3/4 × 3 7/8 × 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This daguerreotype, known as "Portrait of a Man and Woman," dates from around 1850. The artists are anonymous, but what strikes you first? Editor: Well, immediately, the stoicism. Their poses, their faces...there’s a weight in their expressions. They embody a kind of restrained emotion. I can’t help wondering what constraints were placed on gender roles and societal expectations that might have contributed to the expressions. Curator: I see that, definitely. The formality is striking. It feels intentional, doesn’t it? Consider the composition, with its almost symmetrical balance and the meticulous framing of the figures. It’s a constructed image meant to convey something specific, some ideal. The gold frame is symbolic here. Do you see a visual tension created? Editor: Absolutely. This wasn't just a photograph; it was a declaration, a presentation of self that aligned with the Victorian values of the time—duty, propriety. Looking at the ornate details in the frame makes me think about the cost. This wasn't accessible for most of the population. There's an inherent economic and social narrative within this one picture. Curator: Yes, precisely. A Daguerreotype was quite expensive, but think of it another way: their very presence captured in a lasting form challenged the very notion of impermanence! Their clothing, particularly the lace details and the somber colors—they speak to established social codes. It seems as if their attire itself operates as a symbolic language. It speaks to their roles and their respectability. Editor: And yet, beyond those confines, I sense a quiet strength, particularly in the woman’s gaze. Perhaps it is just my contemporary reading. I mean, it speaks to the resilience women especially required as caregivers and upholders of moral codes at the time. The hands tell a story: her's clasped formally, his loosely resting with strength. It's like we're looking at a coded tableau. Curator: So true. Her bonnet suggests a religious modesty too, wouldn't you agree? Though presented formally, these pictures carry individual expression beyond their prescribed codes. Each of us, after all, is the bearer of history. Editor: Ultimately, that intersection—the blend of controlled performance and lingering individual humanity—that’s what makes this image so compelling. Curator: Yes, this portrait serves as an extraordinary visual record of the early days of photography and the narratives they can unearth. Editor: Exactly. It is both a historical record and a continuing dialogue, always reflecting our present-day concerns back at us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.